DIY Art and Glasgow Zine Library

We chat with three artists programmed for the now-cancelled Glasgow Zine Festival to discover what makes zine culture and DIY arts institutions so powerful

The cultural casualties of the coronavirus are almost too numerous to count. Glastonbury Festival has been cancelled, Glasgow International has been postponed, and Eurovision is currently 'exploring alternative programming', to the relief of thousands of music fans (and the consternation of just as many others).

As devastating as these big-name cancellations are, some of the greatest losses to the arts and culture sector will be the smaller festivals, festivals whose funds are limited but whose programmes are generous. Glasgow Zine Festival, organised by the Glasgow Zine Library, perfectly epitomises the community-led focus and grassroots action that such smaller-scale events bring to the table.

Its 2020 programme, sadly indefinitely postponed, offered a space for attendees to harness their creativity as a form of both personal and public expression, with talks on creating inclusive spaces, zine workshops on self-care and mental health, and creative explorations of Black feminism. These kinds of events, and the organisations such as Glasgow Zine Library who are prepared to curate them, are fundamental to our cultural lives because they understand our culture to be diverse, plural, and ongoing in a way that larger festivals often cannot, or do not, reflect.

Inspired by Glasgow Zine Library’s dedication to supporting the arts, we caught up with three of the artists featured in their programme, to find out more about their creative practice, their relationship to the festival, and why the local arts matter. In the meantime, until they can reschedule these events post-pandemic, the zine library are running an incredible roster of free, online events and workshops – check out their Twitter for up to date listings.

Rose Sergent

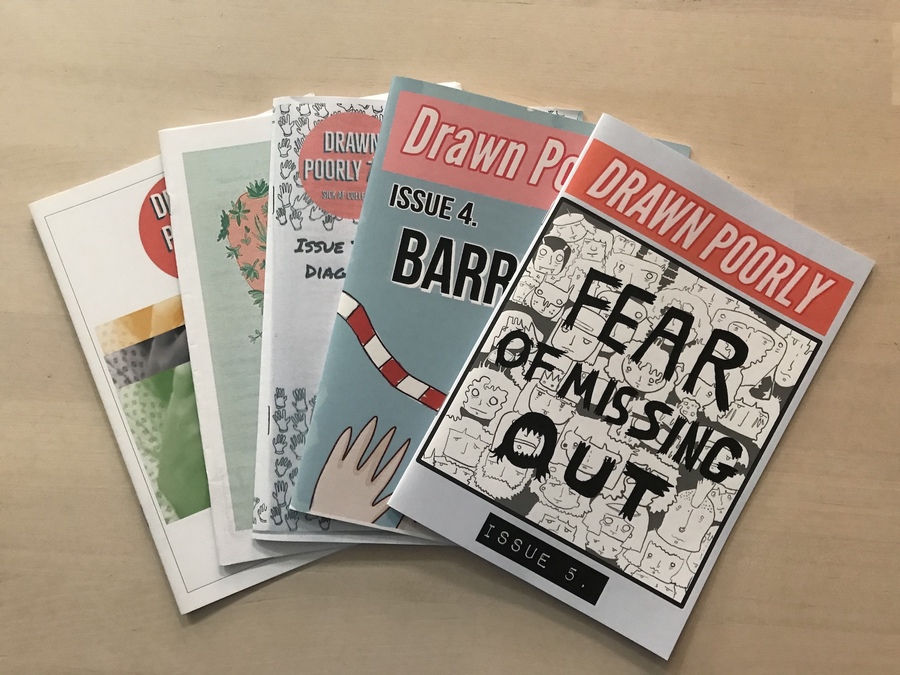

Rose Sergent is a Manchester-based freelance artist and facilitator, and the founder of the Drawn Poorly project, a series of zines that examine life with chronic and mental illness and disability. “My work focuses on using arts as a force for change which is central to the Drawn Poorly project,” Sergent explains. Beginning as a single zine in 2017, the project has since expanded to include five separate issues, each focusing on a different core theme surrounding illness: identity, relationships, diagnosis, barriers and FOMO. “All the zines are collaboratively created,” Sergent stresses. “A huge number of creatives contribute their work, which allows the project to be as multidimensional as living with conditions is.”

Sergent is explicit about zines being the perfect medium for thinking through issues and frustrations surrounding disability and health. Their unregulated nature, free of the constrictions of traditional publishing and distribution, allow for narratives that are otherwise often silenced or ignored. “What we have to say can be moulded into a particular way – to provoke sympathy. Through zines, creatives can speak openly about their experiences and reach others who feel the same.”

As much as the Drawn Poorly project depends on the creatives who collaborate to make it happen, it also draws on local festivals and events to reach as broad an audience as possible, and to give everyone living with physical or mental disability a chance to creatively articulate their lives. In 2019, for example, the project was featured in the Edinburgh Fringe programme, with a series of Let’s Make Sick Art workshops.

“The idea was to engage brilliant creatives and explore how the arts can be more widely accessible to people with health conditions,” Sergent explains. When the subject turns to Glasgow Zine Library, Sergent is deeply appreciative. “They are forerunners for running accessible, inclusive events. They ensure pronouns are asked, they provide a quiet hour at the beginning of the day, and make sure each stall holder has everything they need. These spaces are incredibly important.”

Jules Scheele

“Reading zines produced by other queer people was a very important part of my figuring my personal stuff out,” Jules Scheele muses. Working as a freelance illustrator, comics artist, and facilitator, Scheele’s work focuses primarily on mental health, queerness, activism and community, through their own personal stories. “I use autobiographical comics to take my personal experiences with these subjects and try to untangle and make sense of them – hoping that this will also resonate with other people and maybe make them feel less alone, like reading other artists' autobiographical work often does for me.”

The accessibility of zines makes them ideally suited to this kind of marginalised representation, Scheele claims. “Highly produced art zines are gorgeous, and there's definitely a space for them, but at their heart zines are about having an idea, grabbing a pen and some paper, and then going down to the shop to get them photocopied,” they emphasise. “Zines don't have to be perfect, and they don't have to appeal or be marketed to a mainstream audience.”

This materiality of zine-making is exactly why the zine festival is such a necessary event. “Spaces like Glasgow Zine Festival are super important – being able to communicate in person, discover new stuff, and get your work into people's hands is invaluable,” Scheele explains. And it’s not just limited to the zine festival.

“I think Scotland is pretty good for this: apart from Glasgow Zine Festival you also have the zine fair in Dundee, and various little comics fairs, but you also have brick and mortars like the Glasgow Zine Library and queer, indie bookstore Category Is Books, who also sell tons of zines by local artists and beyond. These events bring together the community and give us a chance to broaden our horizons and make connections, which can result in amazing new stuff.”

Natasha Ruwona

Natasha Ruwona is an artist, writer, critic, and facilitator, whose work examines how post-colonial, de-colonial and anti-colonial methods can both produce and dismantle structures of power. Although not strictly a zine artist, Ruwona is intrigued by the ways in which zine-making can intersect with other de-colonial and anti-colonial work in the arts.

“Decolonisation has definitely become a buzzword,” Ruwona explains, “which is why I have begun using it less and less. Anti-colonial feels more useful because all structures – and white people! – are inherently colonial. Decolonising isn’t enough, we must commit to creating new structures that are anti-colonial in their methods.”

As far as Ruwona is concerned, this goes for zine-making too, particularly as zine culture’s roots were originally rooted in eschewing dominant structures. “I think it's important to make zines, and the arts generally, as accessible (which is a mode of anti-colonialism) as possible,” she underlines firmly. “The cost of zines is often a barrier to my accessing them, especially when they are so effective and can be very simple to make. It takes away from the radical, DIY nature of this form of art-making, which I find super disappointing.”

Places like Glasgow Zine Library, which promote creative accessibility, are so important for this very reason. “Having moved to Glasgow from Edinburgh not so long ago, the thing that really excites me here is the DIY culture,” Ruwona enthuses. “There are constantly festivals happening, which is super cool. It’s so important to have a rich and exciting community for and by creatives.” Moreover, institutions such as Glasgow Zine Library are needed because problems of colonialism and exclusion within the arts are, by their nature, institutional and structural. “We need more people within arts organisations, from higher up, to commit to anti-colonial methods within their organisations,” Ruwona says. “People expect change to be made from the ground up, which doesn’t make sense.”