Primavera and the post-pandemic return of music festivals

Now that the dust has settled on the 2022 return of Barcelona's Primavera Sound festival, we take a look at the post-pandemic return of the major music festival

A crowd has many faces, depending on where you’re standing.

Over the past two years, there have been moments for many of us when a crowd has simply been an image on a screen. Sometimes that has been a rousing image of connectivity and solidarity, such as the community triumph on Kenmure Street, wherein a teeming, cheerful mass of people stood between their neighbours and nefarious forces of the British state. At other times pandemic-era images of crowds have been more disquieting, however, as in the wild-eyed surge of the Capitol Hill riot, wherein a hoarse swarm of pale faces battered against the door of American democracy.

Now that the world is slowly and unevenly opening back up after two years of relatively cramped, isolated existence during the pandemic, we are starting to encounter crowds again, not merely as distant images on a computer screen, but as heaving, breathing immediacies of human life that – both for better and worse – can swallow us whole.

Nowhere is that more the case than at Barcelona’s Primaveravera Sound, one of the world’s most significant and diverse music festivals – which finally relaunched this summer after two cancelled editions in 2020 and 2021. Here, while it is truly exhilarating to encounter so many live musicians again in one place at one time, it is rather that electrifying experience of being part of a flailing forest of human bodies that is the most visceral reminder of what we have missed over the past two years: that dense, rowdy, togetherness of being cheek-by-jowl with folk you’ve never met, who nonetheless momentarily become fellow travellers when sharing the experience of live music.

For the most part, being part of a crowd again at Primavera is absolutely glorious. There can be few things further removed from the closeted experience of lockdown than joining one of the many pits that break out during the joyous, slapstick post-punk of Les Savy Fav’s Patty Lee, or the white-hot fury that erupts like lava during anonymous, Detroit hardcore collective The Armed’s Thursday-night set on the Plenitude stage. Here the chaos of bodies is at its most anarchic, and there is a glorious, if bruising, catharsis to be found in trampling underfoot any remaining notion of social distancing when throwing yourself into the pit’s ever-changing constellation of human collisions. Crucially, though, no-one has forgotten their pit etiquette, and there is something newly moving about the way in which the havoc halts immediately to pick up anyone that falls. Here, the crowd may be chaotic, but it still knows how to look after its own.

Image: Pavement at Primavera Sound by Magdalena Zehetmayr

Elsewhere, there is something equally glorious about the enormous, thousands-strong singalong that accompanies Pavement’s triumphant headline set on Primavera’s first official day. Here the scruffy, slacker rock of Wowee Zowee and Brighten the Corners becomes a sort of folk music, assuming a towering grandeur from the vast, unruly chorus of voices that buoy along each of the set’s 27 songs.

The sheer energy radiating off their audiences does not seem lost upon many of Primavera’s performers. Given the likely diversity of personal circumstance, the bracing shock of being confronted with a crowd seems a fresher experience for some artists than others. In particular, Little Simz, gloriously un-introverted on the Cupra stage (Primavera’s de-facto Roman amphitheatre), frequently seems to need to take a moment to soak in the dazzling warmth of the crowd’s response. Watching her process, seemingly anew, the feeling of facing a thousand faces shouting her name is surprisingly emotional. It’s not something anyone is taking for granted, and there are moments when something like love seems to pass between artists and the crowd in front of them; a recognition of something long-missed, and now shared again.

Just one head among many in the crowd, we cried during Helado Negro’s gorgeous, crowd-sung breakdown of Running, when Nick Cave sang for his sons with such heartbreaking dignity and lucidity, and pretty much all the way through Mavis Staples’ ebullient set in the Auditori Rockdeluxe; all three are musicians who address you so directly, and conjure such a keen sense of togetherness among their audiences, that it's difficult not to reflect back upon the past two years and finally feel some sort of relief. Equally, on stage, Kacey Musgraves is noticeably emotional as she walks off to the extended, triumphant outro of Slow Burn, and Caribou’s Dan Snaith, after an hour of sky-scratching euphoria, seems almost bewildered by the response he unleashes from a beaming mass of bodies, many of whom – like us – have been waiting two years to feel this good.

Image: Nick Cave at Primavera Sound by Magdalena Zehetmayr

And yet: there is unfortunately another face still to the crowd, which begins to show itself on Primavera’s borderline dangerous first day back. Amid the dizzying joy of being back among people and among music, an insidious unease begins to spread within the growing realisation of just how difficult it is to move and – beyond that – meet basic needs. It quickly proves near impossible to get any food or water during interminable waits at the bar (or the tiny number of fountains the festival have deigned acceptable), and many of the dense thickets of bodies become paralyzingly tight; and what for many was warm and convivial quite quickly becomes – with uneasy recollections of the Astroworld tragedy – suffocating and scary. (And within these mindless scrums, of course, is COVID aplenty; a now-inevitable risk at an international fulcrum of this sort, to which various members of The Skinny’s team who were in attendance themselves succumbed). Rather than the interconnected solidarity of Kenmure Street, or the violence of Capitol Hill, here there is simply the blank panic and numb collision of far too many people crammed into far too small a space: one enormous, mindless pit where no-one has the space or wherewithal to pick each other up.

The fault, in this respect, belongs in no way to the crowd, but entirely to Primavera themselves, reflecting an increasing tendency (as we have explored before) over the years preceding the pandemic towards an all-too-familiar sense of expansionism and extractivism. The ripple effects from Thursday’s very uneasy opening night were so far-reaching, that Primavera subsequently had the dubious honour of spawning its very own moment of Discourse, in which the sheer volume of unhappiness and distress expressed on social media led certain Extremely-Online hipster Twitterati to declare that the notion of capitalism was making festivals uniquely bad in 2022 was simply folk being too precious. Festivals, we were told (by those who, typically, were neither in attendance themselves, nor seemingly had ever attended Primavera before) have always been disorganised and overcrowded, and those crying capitalism at Primavera were merely stale, ageing curmudgeons better sticking to real ale festivals.

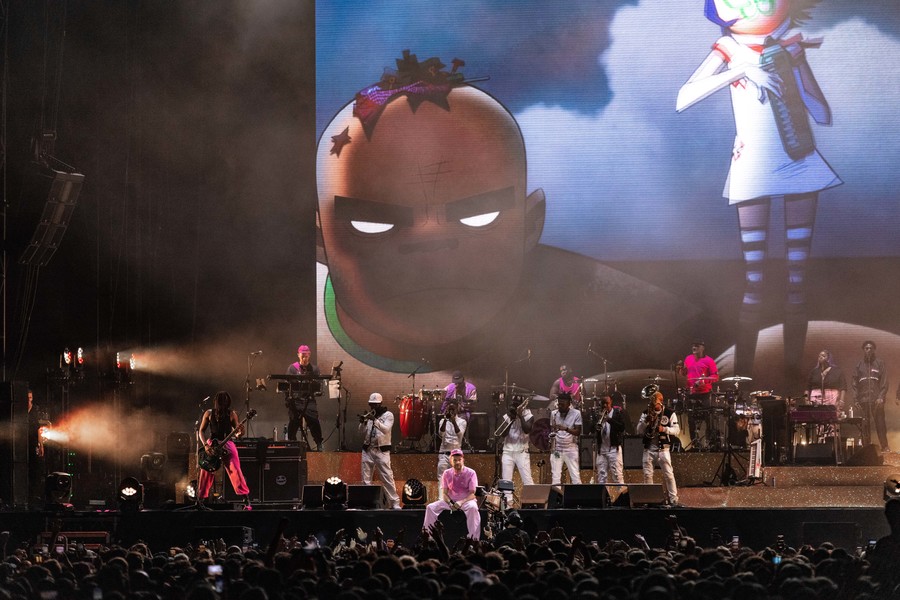

And yet, what else should we call the sale of strickeningly greater numbers of tickets for the same, increasingly cramped space? Or the increasing proliferation across the festival of NFTs, crypto, on-site branded clothing chains, and the replacement of long-term alliances with ATP and Pitchfork with major car and energy companies? Or, indeed, the increasing outward expansion towards events now in Los Angeles, Sao Paulo, Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires? It has become increasingly difficult to keep track of the many artists haemorrhaged from Primavera’s Barcelona lineup: some, such as Massive Attack and The Strokes required public acknowledgement, whereas others – such as Japanese Breakfast and Brockhampton – disappeared quietly as if they were never there at all. Increasingly there is a sense the empire has grown so big, that the careful curation of one particular festival is just small potatoes. Gorillaz alone had De La Soul and Mos Def in Barcelona for both weekends simply to guest on one or two tracks each; headliners-in-waiting who could have amply filled the shoes of some of the absentees, had there perhaps been less of an emphasis on bottom line.

Image: Gorillaz at Primavera Sound by Magdalena Zehetmayr

We’ve all been at shit festivals, and yet Primavera has to-date inspired such loyalty because it has not been one of them. Primavera is certainly not the first example of the easy complicity between superficial commitments to sustainability and emancipatory, ‘be yourself’ individualism and the brutal extraction of surplus value: the green- and rainbow-washing of neoliberalism. And yet: given it’s history as one of Europe’s most beloved music festivals, and as a space wherein a dizzying diversity of musics have been held truly sacred, it is particularly distressing to see just how comfortable the easy mantras of sustainability are becoming here with the crushing logic of profit.

Throughout the festival there is evidence that that extractivism is starting to pollute the very waters it is seeking to plunder. Nala Sinephro, one of 2022’s most essential musicians, cuts her set of gorgeous ambient jazz 25-minutes short when it becomes impossible to even hear her harp within the overpacked venue of loud, chatty voices only in attendance – we assume – because, if they didn’t get into the venue early (given the intensely overcrowded, oversold nature of Primavera’s city gigs), they would have no chance of seeing Jorja Smith. The cathartic, cleansing ritual that begins Angel Bat Dawid’s set is almost completely drowned out by Pond, playing one stage over for what seems like the 15th time during Primavera’s expanded dates.

Elsewhere still, #pulltheplugontheboilerroom starts to circulate on social media when the new Boiler Room stage, crammed into a small corner between two of Primavera’s principal stages, drowns out otherwise sublime performances by The Weather Station and Stella Donnelly. Here the sacredness of music that has always been one of the key draws of Primavera is itself in danger of being crushed in the crowd, as the festival sells ever more tickets, with ever diminishing regard for the impact upon both artists and audiences.

In these terms, the oddly defeatist suggestion from a notionally leftist commentariat that the diminishing returns of Primavera are simply a case of ‘shit happens’ or ‘you’re too old’ risk uselessly masking the slow-moving tragedy of a beautiful thing being crushed within the grinding wheels of neoliberalism. There is a river of music that flows globally between communities – a churning, bewildering torrent of feeling and sensation finding ever-new points of connection and commonality – that is the polar opposite of the cold, transactional Gesellschaft of late neoliberalism.

Despite the growing oil in the water, Primavera still remains one of the best places to throw yourself into it and get beyond our own isolated individualities into an expansive, affirming togetherness. Like many things, however, as the world opens up again post-pandemic, that sense of rightness cannot be taken for granted. Primavera can still, just about, give you some of the greatest moments of your life, but increasingly they risk being drowned out in the cacophony of a festival more interested in capital than curation.