Food For Thought: On Scotland's food past, present and future

Scotland has a rich tradition of hearty, distinctive cooking – so where has it gone? And how can we revive it in a globalised, hyperconnected world? Grant Reekie takes a look at Scotland's culinary past, present, and future

When Anthony Bourdain came to Scotland in 2015 to film an episode of his Parts Unknown TV series, he drank alone in the afternoon, ate chips, cheese and curry sauce, sampled Irn-Bru, and learned about knife fighting in the derelict Govan graving docks. He then decamped for the Highlands, where he shot a deer through the heart. On first viewing, I thought he’d done a pretty good job of summing the place up.

Now though, I wonder what that episode really says about Scotland as a nation. It's hard not to feel there's a certain lack of distinctiveness in the food consumed, a lack of coherent Scottishness. This mirrors my experience that when asked about ‘Scottish cuisine’, many Scots either draw a blank, or cringe as they describe haggis and deep fried Mars bars.

The truth is, what we really eat on a regular basis is a kind of creolised international diet. Across the country, pub and restaurant menus often rely on appropriating and modifying dishes from other cultures. Taiwanese bao buns. Korean fried cauliflower. Tacos. Katsu curry. But dishes repeated ad-nauseum across 'pan-asian' or 'street-food' menus quickly become flavour of the month. Too often, ramen becomes yet more thin soup. I can’t help but wonder; why aren’t there more interesting Scottish restaurants in Scotland? Does the 'Scottish cringe' prevent us from valuing Scottish food? And what even is Scottish food, anyway?

Florence Marian McNeill made a pretty good stab at answering that last question almost 100 years ago, travelling, sampling and collecting recipes from all over Scotland, putting years of research into writing the definitive text on Scottish cooking: 1929’s The Scots’ Kitchen – its traditions and recipes. This compendium, and the excellent Broths to Bannocks; cooking in Scotland 1690 to the present day (1990) by the equally indelible Catherine Brown, make it clear that there were, and are, a slew of distinctive recipes characteristic to this part of the world.

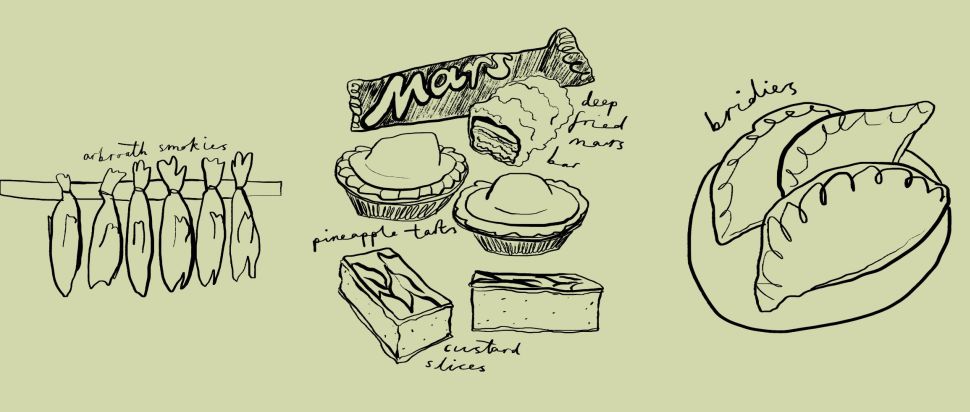

To name just a few examples, we have clootie dumpling, cock-a-leekie, Scotch broth, partan bree, Arbroath smokies, Finnan haddies, and cured mutton hams. At its heart, Scottish cooking was once based mainly on wholegrain barley and oats, root vegetables and kale, augmented with a little meat, mostly in soups and broths. We made good use of excellent dairy, and consumed lots of oily fish. We have a great tradition of baking – oatcakes, tattie scones, rowies/butteries, bannocks, bridies, pineapple tarts, custard slices, fudge doughnuts and glazed strawberry tarts are all brilliantly Scottish, or at least have a distinct style in Scotland.

Why then do we so rarely see these items on a menu? Our tastes have changed, certainly, as they have across the world. But your average Italian or French citizen is fiercely proud of their ancestral recipe book, keen to hold on to their culinary roots, in a way that we just aren’t in modern Scotland.

Roots are a funny thing. They are both a link to the past and a source of growth, something that can nourish you and encourage development, or hold you back. You can be rooted in place, or rooted in culture. They are also a category of ingredient (neeps, carrots, onions etc). Those particular roots once made up much of the base in Scottish cooking in the same way sofrito or mirepoix do in Italian or French cooking. We live in a time of culinary uprooting, where memes, ideas, ingredients and flavours can travel freely; perhaps it’s inevitable that the direction of travel in our culinary explorations is to resign Scotland’s older, earthier style of cooking to the history books.

As L.P. Hartley first said: “The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.” We certainly do things differently in modern Scotland, and in most cases that’s a good thing. I wouldn’t want a rigidly traditionalist culinary hegemony, of the sort which sometimes stifles young French and Italian cooks. Experimentation is good, taking on and adapting influences is the root of creativity. But we need to be careful.

This shift away from local roots isn’t unique to Scotland, and is part of an international cultural shift towards what food writer Bee Wilson refers to as ‘The Global Standard Diet’. Researcher Colin Khoury led a group of academics who first identified this paradoxical shift, in which locally diets have diversified, but at a global level become more homogenous. Grains dominate – wheat, rice, maize and soy make up 60% of calories grown by farmers – and by some estimates, just four corporations control 90% of the global grain trade. The Global Standard Diet is a signal of the emerging cultural trend towards homogenisation. We should be wary of sleepwalking into creating a monoculture of cuisine and culture that mirrors our increasingly unvaried agricultural landscape.

Cultural diversity is good, I want to be clear about that – this is no Brexit-Britain call for Scotland to be Scottish. I love multiculturalism, selfishly, for the opportunities for deliciousness it provides. A walk down Byres Road and into Partick yields wonton soup, roast duck, curry houses, banh mi, steaming bowls of pho, and bibimbap, and I couldn’t be happier to have those options. However, diversity is by definition made up of many different elements.

Scottish food, the ancient cooking of this country, adapted to its climate and ingredients, deserves a place in the pantheon. Culinary diversity, like biodiversity, enhances and strengthens itself through having many differently evolved forms. Will the Scottish branch of the culinary evolutionary tree continue growing, or wither away? This year, the Scottish Government will set out a plan for becoming 'A Good Food Nation'. This aims for us to 'take pride and pleasure' in our food. I hope that we can look forward to achieving that ambition, but let’s not forget to look backwards as we go.

Grant Reekie is a chef, campaigner and professional cookery lecturer based in Glasgow. He runs cookery blog @thatsyerdinner on Instagram, and occasionally hosts pop-up supperclubs under the same name.

This article is from issue one of GNAW, our new food and drink magazine dedicated to sharing stories from across Scotland’s food scene. Pick up a free copy from venues across Scotland, and follow GNAW on Instagram @gnawmag