The Taste of Home: Albanian food in Edinburgh

Our food traditions connect us with family, friends and place – but sometimes it takes a bit of digging to tease them out. Maria Morava looks for a taste of Albanian food in Edinburgh, and finds a community reclaiming its culinary identity

Growing up with my Albanian dad and grandmother, pizza was my favourite food – and my dad, having spent time as a refugee in Italy and a pizza cook in the USA, made it best. He’d show me how to knuckle the dough into a disc and toss it in the air where, each time, I swore it would reach and stick to the ceiling. I tried to mimic him, but my clumsy knuckles would stretch the dough thinner and thinner until the light threatened to break through, unable to hold it all. Pizza night was the rare night my dad cooked instead of my grandmother, who would always make Albanian food – something I found comforting, but less impressive.

What I didn’t know then was that my dad’s pizza speciality was not separate from my grandmother’s traditional Albanian cooking. They existed alongside each other, reflecting different but intersecting migration journeys – not only for me and my family, but for Albanian migrant communities around the world, who, in overwhelming numbers, populate the Italian and Greek restaurant industries. The pizza I loved growing up became emblematic of the personal and political histories that shaped my sense of self.

It was this understanding that brought me to La Casa, a Mediterranean small plates restaurant in Dalry; I had heard through the grapevine that La Casa was Albanian-run. I wanted to see what the Albanian scene was like in Edinburgh, as it is so often eclipsed by Italian and Greek branding in other cities. While I found what I expected, I found much more, too – a community reclaiming, shaping and sharing traditional Albanian foodways. And a community that wanted me in it.

I walked into La Casa timid, the way that I always am interacting with Albanian people who aren’t my family. My language is poor and the longer I’ve lived and moved, the further away I feel from the people and food I grew up with. Yet the restaurant instantly felt like home. The decor looked like a house my dad had built for us himself in the 2010s – rustic, with exposed brick, Mediterranean tiling and dark-stained wood. I remember my dad saying he wanted our house to look Italian. I locate the person I’m meant to speak to, Tzouana Vitou, and wait for her to finish cooking an order before we sit down.

Tzouana can cook everything, she says, and has been working in the food industry since she was 15. I tell her I want to talk to her about traditional Albanian food, and she lights up.

The question of what is 'traditional' is complicated for Albanians. The country sat at the crossroads of different empires for centuries and, until the 90s, endured decades of communist rule that closed its borders and weakened food traditions through restrictions on dairy and meat. Regional varieties of dishes were unable to be passed down, along with basically all religious beliefs.

But Tzouana doesn’t seem conflicted. She knows what is traditional because it is what she makes in her home; it’s what my grandmother made in my home, too. She talks about byrek and baked fish and tavë kosi. She talks about the beaches of Sarande where she grew up, so blue you can’t tell where the sky starts. It's also where my dad served in the Albanian army during the regime, before he and 5,000 other citizens stormed foreign embassies in 1990, enabling their escape as asylum seekers in Italy and beyond. Western coverage of this accelerated the fall of the regime. I am hooked on Tzouana’s every word, and before I can take a deep breath she is asking me to come eat Albanian food with her and the staff, who she cooks for often.

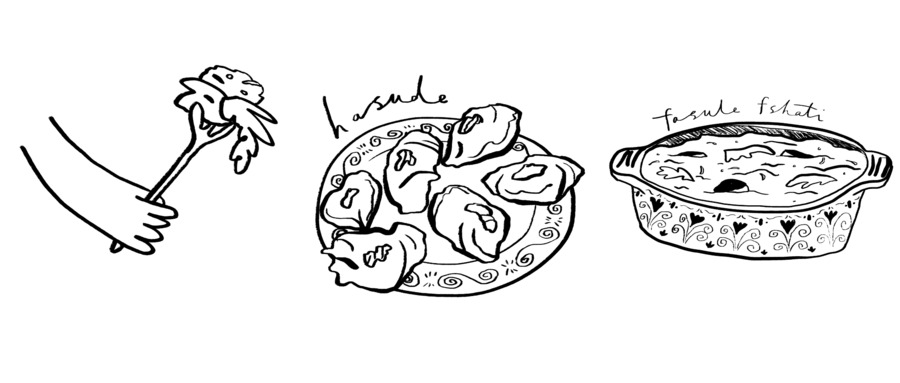

When I return a few days later, Tzouana apologises. It’s Sunday, she says, and she hasn’t made much food for lack of ingredients. This is before she muscles a massive bowl of 'country' white beans, fasule fshati, to the table, followed by an even bigger casserole of roasted aubergine, potato and pepper, tavë me perime, and two clay pots of still-bubbling feta and meat in fërgesë me mish. Salad – “simple, no peppers, no nothing” – and bread on the side. Hasude, a dessert made from cornstarch, goes down like a thick pudding, sharp with red-brown caramelised sugar.

Illustrations: Thea Bryant

The staff eat in the dining room together. While we eat, people pass by the window and marvel at the spread – when I hear “Mashallah”, a relic of Islam that persisted through half a century of communist atheism – I realise they are Albanian. Some of them are asked to join us. I’m observing this as I eat the tomato-stewed beans, soak up the rich oil with my bread and save the fërgesë for last. I cannot believe that I am eating this, listening to the Albanian language surround me in Edinburgh. Since I was a child, I’ve had more pizza than I can count – some undoubtedly from Albanian hands. But since leaving home, I’ve eaten Albanian food only a handful of times.

A 2008 piece in Philadelphia Magazine about Albanians in the pizza industry warns, “The Albanians are coming!” describing the country as a “small, poor, corrupt Balkan state” full of people you don’t want to “fall in with.” Xenophobic narratives like these persist in the UK to this day – most recently in the 2022 governmental panic around Albanian immigration.

When I asked Tzouana if Italians and Greeks know how to make Albanian food the way she knows how to make their food, she shrugs and shakes her head. Migration in Albania flows one way. Despite my questioning – my implicit urging of a sense of unfairness – she is resolute: She loves Albanian food. She finds pizza boring. She is, in the cracks of the Mediterranean food industry, bringing forth clay pots of fërgesë to be shared. That’s really all there is.

My journey from dough-clumsy hands to the communal table at La Casa is, for me, a profound politic. A peek behind the curtain on my favourite childhood food revealed a history and cultural identity just as fragmented and diffuse and unsure as I often feel. But I realise there’s community in that too, right down the road. My tongue might falter around my own language but it knows the way these white beans should taste.

“Send a photo to your dad,” the manager of the restaurant instructs me. I do and he replies: “Looks great.” I won’t get more from him. There’s a lot I don’t know and might never know about where I come from and my history, but I do know that the shape of my longing and confusion has a place at this table.

Maria Morava (she/they) is a writer and facilitator based in Edinburgh. She is co-organiser of Rehearsal Space, a gathering to practice liberated futures, beginning sessions this summer.

This article is from issue one of GNAW, our new food and drink magazine dedicated to sharing stories from across Scotland’s food scene. Pick up a free copy from venues across Scotland, and follow GNAW on Instagram @gnawmag