GSFF unearth First Reels

Ahead of Glasgow Short Film Festival's First Reels retrospective, GSFF director Matt Lloyd gives us the lowdown on this innovative, forward-thinking 90s short films production scheme

Between 1991 and 1999, the Scottish Film Council, in partnership with STV, ran short film production scheme Short Reels. The initiative saw over 130 shorts get made, including early efforts from Peter Mullan and David Mackenzie, and is notable for the diverse range of talent it supported (over a third of the shorts produced were by women) and the freedom they were given. Many of the films made under First Reels haven’t been seen in two decades, but Glasgow Short Film Festival have unearthed three programmes’ worth of First Reel shorts for the 2019 festival. GSFF director Matt lloyd tells us more.

The Skinny: What were your first impressions when you dived into the work made under First Reels?

Matt Lloyd: I was struck by the sheer volume of work produced through the scheme. I couldn’t find one definitive list of titles, so I pieced it together from various paper sources, and it became clear that there was no one single archive of work. Contrary to what I’d assumed, the National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive’s collection comprises less than half of the 130-plus films produced through First Reels. I managed to see some more titles in STV’s vaults, as well as the three TV documentaries produced each year about the scheme, which gave me glimpses of even more work. This led me in turn to approach individual filmmakers, some of whom dug out 16mm prints from their garden shed. Many others I still haven’t tracked down.

What type of films were made under the scheme?

After volume, the second thing to strike me was diversity – in form, subject, tone, approach and, inevitably, quality. The scheme produced everything from ambitious dramas to experimental non-narrative works, from glossy productions to community projects. Some of it was poor, some of it wasn’t finished. But all of it felt original. First Reels refuses easy categorisation as a scheme. I think this is because to a large extent the filmmakers were simply given small pots of money (anything between £50 and £3000) and left to get on with it. Only in the later years of First Reels did it start to resemble the script-development-led model of the production schemes that followed it.

It feels to me like an attempt to seed and nurture an emerging film culture. This was two or three years before Shallow Grave, and not a lot was happening in Scottish film. So while First Reels may not have been particularly rigorous or strategic in terms of the types of project commissioned, it cast its net wide and drew in a great variety of voices and abilities.

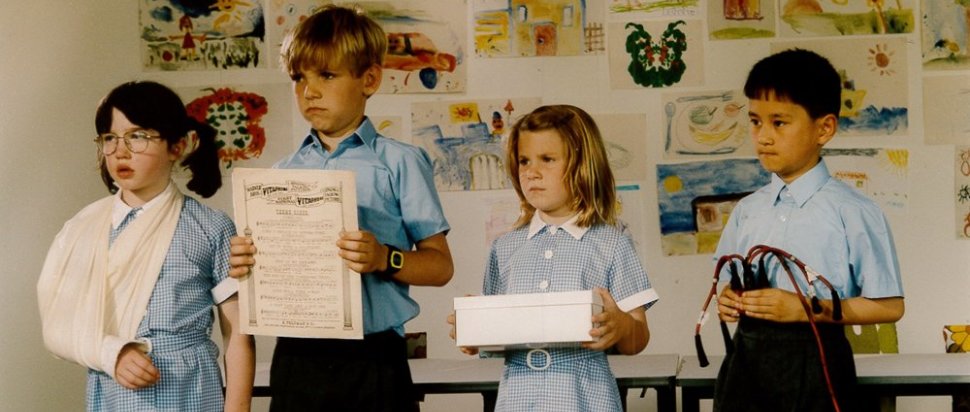

Tool (Dir Shaz Kerr). Image: Kill Jennings

Were there any surprises in the films you uncovered?

Loads. I was only really familiar with Peter Mullan’s two First Reels films, Close and Good Day for the Bad Girls, as well as some of the later works, Stephen Morrison’s Frog or Wendy Griffin’s Mirror, Mirror. Many of these works were made by people who went on to build a career in some aspect of film production. But there were names who were totally unknown to me – Shaz Kerr for example, whose film Tool is a captivating yet politically-charged work about tropes of West of Scotland identity, yet has a very European sense of space and the absurd. Travis Reeves is a talented sound designer, but Sad to Say But Sammy is Dead demonstrates considerable understanding of visual storytelling, not to mention meticulous production design, evoking the filmmaker’s childhood in Australia through specially-built sets.

Can you talk about First Reels legacy?

The biggest names are of course Mullan and David Mackenzie. Both won awards for their First Reels films, and David Mackenzie was invited back to direct the First Reels TV documentaries, a task he embraced with considerable gusto. He threw out the rather bland Film ’92-style format and introduced a madcap opening sequence and flash frames of credits, encouraging viewers to set their video recorders if they wanted to read the credits. In the majority of cases, those filmmakers who’ve remained in the industry have taken on different roles; there are very few actively practising directors. And although women comprise about a third of the directors represented by the scheme, I think I could count the number of women still directing on one hand.

Talking to some of the First Reels filmmakers, the biggest impact for them was simply having the space, and some modest resources, to try things out.

What can we look forward to in GSFF’s First Reels programmes?

Thanks to the support of Film Hub North’s Changing Times programme, we’ve been able to dig several titles out of the Moving Image Archive which weren't currently available to the public, and to scan some prints not held in the archive. David Mackenzie’s Dirty Diamonds is a real find: it’s an impressive 25 minute production of a film noir pastiche, and though far from perfect, it’s an impressive production of a very absorbing story. Peter Mullan’s Close succeeds where many shorts fail, wedding Grand Guignol horror to expressive poetic imagery and a genuine social conscience.

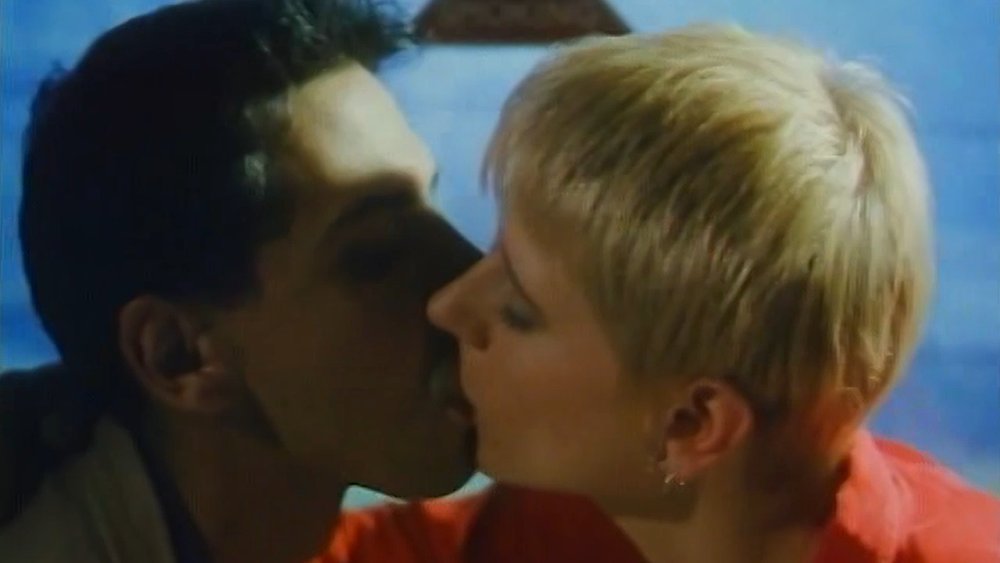

I’m a big fan of Lucy Enfield’s The X in Scotland, which considers racial identity in an overwhelmingly white culture. Hannah Robinson’s Relax is less well known than her later short Sheila, but to my mind far more enticingly framed and edited. Suzanne Morrow’s Bust is an inventive essay, while Gillian Steel’s A Currency for the Superstitious is Margaret Tait on speed.

Relax (Dir Hannah Robinson)

Do you know why the scheme ended in 1999? And can you imagine a similar scheme working today?

I don’t know for certain, but clearly First Reels had been overtaken by the more rigid schemes that had been introduced since 1991: Prime Cuts, Tartan Short, New Found Land, later Cineworks and Digicult. Producing fewer films with higher budgets perhaps gave commissioners more control over the results.

On the other hand, First Reels was occasionally criticised for relying too heavily on voluntary labour and in-kind support – which is perhaps not a good look for a publicly funded initiative.

I’d love to see a return in some form, and arguably it’s considerably easier to create decent images with the technology available to almost anyone now (which is not to say I’m not jealous of the First Reels filmmakers, cutting 16mm rushes on a Steenbeck). I think the vital element of the scheme was freedom – freedom to take risks, freedom to fail, freedom not to deliver a tidy finished product – and I can’t help but wonder that a bit less risk-adversity could produce a far greater range of voices again. Far more is happening in Scottish production than it was in 1999. What is arguably lacking is a diversity of vision, there are few filmmakers who surprise us. At its best, that’s exactly what First Reels did.

Glasgow Short Film Festival runs 13-17 March – full programme here

Three programmes of First Reels shorts screen at GSFF – most of them for the first time in 20 years

First Reels 1 – GFT, 16 Mar, 3.35pm

First Reels 2 – CCA, 16 Mar, 7.30pm

First Reels 3 – GFT, 17 Mar, 3,15pm