Michael Pedersen on Boy Friends

As he prepares to unleash his first book of prose, Boy Friends, we meet Michael Pedersen to discuss friendship, love and grief

In a book that’s filled with musings and fascinations and reminiscences on friendship, there’s a section towards the end of Boy Friends that imagines a more constitutional way of looking at things. Author Michael Pedersen leans back against his erstwhile legal training to conjure the concept of a friendship contract. What would it be like if there were a set of tenets and principles that covered fidelity, forgiveness, behaviour, grief?

“It would enable us to view friendship on our own terms and safeguard ourselves from toxic friendship or friendship under duress,” he mulls. “What are we offering as a friend under these circumstances, and what do we expect in return?”

What happens when you push friendship too far? What are the clauses for termination? And what about when a friendship is taken from you far sooner than you want? In part, Pedersen is ruminating on the hierarchies of grief – where do we stand among the hordes of mourners, when can we talk about something else, go back to work, post a selfie?

Boy Friends began as a homage to Pedersen’s late and dear friend Scott Hutchison, growing into a celebration of male friendship and a deep dip into the highs and lows of mental illness and grief.

“[The idea of a friendship contract] helped me understand where I was without [this] friendship. Here’s what we’re entitled to when this is no longer around: periods of grieving, emotional compensations. Imagine all that was impossibly spilled down in this fictitious contract. It would give us a bit more of a crutch at a time when the world was crumbling.”

Of course, he goes on to concede, it would be impossible to draft and would have to be constantly evolving. And that’s the thing: ongoing friendships can’t be pinned and spread like a butterfly. So, Pedersen turns his lepidopterism to the ones in his past, celebrating his favourite boy friends gone by. It’s a linear non-linear epistolary read that charts both his life in friends and more or less the year after the loss of his very best one.

Michael Pedersen. Photo: The Portobello Bookshop

As Boy Friends reveals early on, Pedersen is someone who just has a lot of feelings. “That’s what my mum told me during these periods of emotional turmoil, painting the day’s dramatics in positive swirls. I took it to heart, thought of it like a superpower.” For context, this passage comes after he’s held a solo vigil in the rain following his first experience of death – his hamster Pepsi. But this is an identity that seems to fit; Pedersen talks about relating hard to a misremembered Counting Crows lyric, “I feel things twice as much as you do,” in one of those fits of teen angst. It’s only natural that he brings his all-giving, all-loving, all-feeling nature into his friendships.

“I didn’t know where to put all the energy inside of myself,” he says. “I was looking for friendships that wanted to swallow the other person up really quickly. I wanted this comrade-in-arms, this fraternal, all-encompassing bond. I wanted it immediately, and yesterday, and fast.”

This sense of hyper emotionality comes in some sense from the media he consumed, from love songs and poetry and fantasy literature – Sam and Frodo’s companionship in Lord of the Rings seems to have particularly struck a chord. Taking this intensity into early friendships isn’t without its drawbacks, though – friendships made at our emotional zeniths can be short-lived, intense and fragile. Until he actually sat down to write Boy Friends, Pedersen hadn’t realised how many of his seminal friendships – the ones most full of love, entered into most vehemently, and perhaps hardest to deal with – were no longer in his life.

“When I looked back at them and they’d all expired, I was looking for some sort of formula that would make sense of them,” he says. “Because that would give me the apparatus to learn how to celebrate this friendship with Scott which was no longer around for an entirely different reason. I thought if I could work out how to celebrate these lost friendships, then I’d fortify myself to celebrate this friendship which was more cruelly taken away.”

Scott is the entity that permeates the book in the same way he permeated Pedersen’s life: wholly, joyously and lovingly. Their friendship reads like a movie: Pedersen paints him performing under lights that illuminate him in the way he deserves; they take unimaginable trips to South Africa where they perform and drink and tour and love; they eat together, so much food and so many meals – each as bright and bountiful as the imaginary dinner scene in Hook. It’s a fairytale made real, and Pedersen’s poetic voice feels custom-made to twist his words beautifully together to paint each Scott scene with love and care.

“All my memories of Scott are full of joy and laughter and silliness and smuttiness, and there are these deep sentimental conversations, but always completely engulfed in humour,” he says. “He had an interesting face I’d find myself staring at more than any other face. I often was thinking about the mechanics that were going on in his mind. Even as someone who was privileged enough to have very close conversations with him, you only got what he wanted you to have. He was the care keeper of his emotions, because they were so big, abundant and encompassing.”

Pedersen often found himself psychoanalysing where Scott’s face – his gaze – was taking him. He could have been anywhere. And when the news came that Scott was missing, he was everywhere and everything. In the unyielding between-time that punctuated Scott’s disappearance and discovery, Pedersen came across an oyster shell: a bonding motif for the two friends – they published a book together called Oyster a year before Scott died. “I’ve still got it. I don’t see myself giving it away ever.” In death, we tend to give meaning to things we might not ordinarily seek out – perhaps as a way to assert control over the uncontrollable, perhaps yearning for meaning in something so uncanny.

“I do it constantly and with conviction and compassion, even if it’s just to enable me to have the conversation with the world that I want to have,” says Pedersen. “If these curios and bibelots can become a vessel for me to confirm or to assure myself under the circumstances, then for sure I’ll do it.”

Another night, months later, Pedersen sees Scott’s face in a disco ball – a heart-lifting way for him to communicate. “The grief comes where it comes. It’s unpredictable, it’s visceral, it’s this sort of eccentric, capricious beast of a thing, so why not take control over certain elements of that? I think it’s really important for us to do an audit of our memories and our own lives and objects and curios and how they fit into the wider kismet and cosmos of it all.”

The disco ball apparition seems a fitting way to remember Scott: twirling in shattered light as music swells. A glitzy, hedonistic way to remember a friendship that brought so much glitter into two men’s lives. Boy Friends too, its vivid pinks and purples and unyielding tumblings of male love and friendship is just as sparkling, sensual, and sweet.

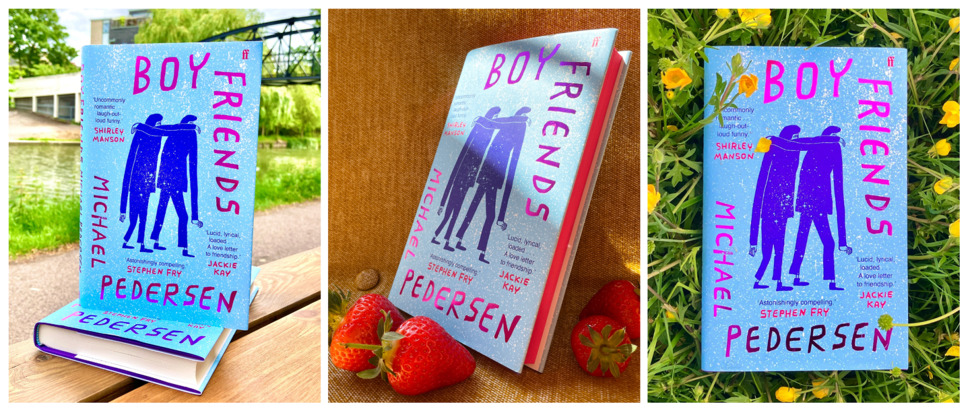

Faber, 7 July, £14.99

faber.co.uk