How can the Edinburgh Fringe become more Accessible?

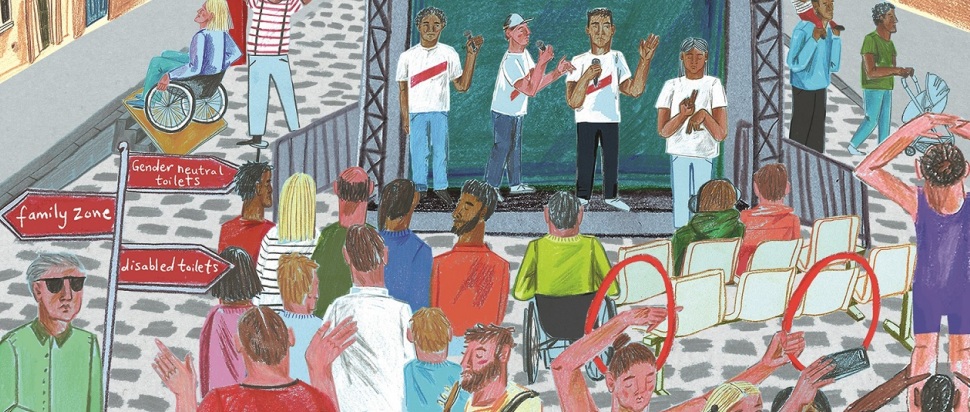

The second instalment of our Fairer Fringe series looks at how accessible Edinburgh's Festival Fringe is for audiences with disabilities

Edinburgh can be a tricky city to navigate at the best of times. Built on rolling hills, and full of cobbled streets and narrow passageways, the (admittedly picturesque) inconvenience of its topography is only amplified during the Fringe, when crowds pour into the city to enjoy the countless pieces of theatre, dance and comedy on offer.

Combine Edinburgh's urban geography with the fact that many shows at the Fringe are staged in temporary pop-up venues – like attics, lifts and basements – and you've got a festival that can seem dauntingly inaccessible to wheelchair users and people with disabilities.

Thankfully, progress is being made. After years of vocal frustration from festivalgoers with disabilities, The Fringe Society are addressing the problem. For 2019's festival, they have been working on a variety of new initiatives including the installation of a 24-hour Changing Places toilet (a toilet with a changing bench and hoist for those unable to use standard accessible toilets) next to Fringe Central, and the inclusion of a Fringe Disabled Access Day (13 July 10am-6pm, at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe shop) which will offer advice and support to people with various access requirements.

This year, 61% of shows on sale are accessible to wheelchair users, with 49% of Fringe venue spaces boasting full accessibility. At just less than half, it's still nowhere near good enough – but when only 40% of venues were accessible in 2017, it's a step in the right direction.

Addressing the full spectrum of disability

The danger, however, is that venues, festival organisers and theatre companies assume that improving accessibility ends with just that: enabling easier physical access. While increasing the number of wheelchair-friendly venues is great, a huge number of people with disabilities do not use a wheelchair – or do, but also have additional needs and requirements that aren't being addressed.

"Disability is a huge and wide ranging spectrum, and people's access requirements can be related to physical, sensory or attitudinal barriers," says Richard Matthews of Graeae, a theatre company with an artistic mission to place D/deaf and disabled actors centre-stage. The lack of focus on catering for audiences with other disabilities is reflected in the 2019 programme – while 2452 shows out of the total 4074 offer wheelchair access, there are only 48 that feature captioning, 36 with signed performance and just 72 relaxed performances.

To their credit, the Fringe Society have been working on reducing these barriers too. They are increasing the availability of sensory backpacks for children and adults on the autism spectrum in venues across the city to 80 this year, and have created a new filter on their website that allows theatregoers to search for shows that meet their individual needs. If very few shows exist that cater to audiences with specific disabilities, however, there is little that the organisers can do.

Matthews argues that creating shows that are as accessible as possible is also the responsibility of theatremakers and companies who are using the festival to platform their work. "The relatively small number of accessible shows will be for several reasons," he says. "One of these will be the issue of cost. Sign language interpreters are paid well (quite rightly – it takes seven years to train!) and it can also be expensive to caption a show as equipment often needs to be hired in. When a large proportion of shows at the Edinburgh Fringe are produced on a shoestring budget, the costs and lack of expertise can often be prohibitive."

However, Matthews insists that there are creative solutions for artists and companies determined to make their art accessible for all. "[Options include] hiring an actor in the cast who can sign, so that BSL can be embedded into the show, or using PowerPoint to project captions onto a clear part of the set," he says. "It's also crucial that access is woven into a production budget from the outset – if we consider it as integral a part of a show as costumes and set design, then we will start to see broader change."

Relaxed performances at the Edinburgh Fringe

The lack of relaxed performances programmed at the Fringe – a term for shows that have been especially adapted for audiences who might benefit from a more relaxed sensory environment, for example by raising the lights or reducing volume – could also be due to a broader problem within the UK's arts scene. The 2018 case of a woman with Asperger's removed from a screening at the BFI for laughing too loudly is symptomatic of a wider culture of gentrified intolerance that is all too prominent in theatre. "In recent history, attending theatre has had a very strict protocol attached to it, and a specific etiquette that audience members are expected to follow," Matthews asserts. It's a protocol that often creates a hugely exclusionary environment – one where audience members feel under pressure to behave in a conventional way, and create no disturbance whatsoever for the duration of the show. The format can create anxieties for people with disabilities that prevent them from attending altogether.

Fringe producers may be worried that diverting from this blueprint may alienate audiences who expect a certain kind of environment at the theatre – but, Matthews suggests, by failing to adapt performances they're missing a trick. "D/deaf and disabled people make up approximately 20% of the populace, so we're a significant market," he says. "If [inclusive] performances aren't offered then the audience won't exist. As the audience base grows, the demand will start to increase and producers will want to continue to meet that." Matthews hopes that the programming of relaxed performances by major commercial producers, such as Disney with their production of The Lion King, will filter down through the rest of the industry and reach emerging companies at the Fringe.

Creating relaxed performances and other types of accessible performance can be a creatively stimulating challenge for companies, too. "At Graeae, we aim to make our productions as accessible as possible, through the creative use of sign language, audio description and captioning, and through offering relaxed performances," he tells me. "These features aren't an add-on, but are creatively embedded into the fabric of the production and intrinsically linked to the aesthetic of the show."

"Bringing attitudes into this century"

Carrie-Ann Lightley, the Marketing Manager of AccessAble, an organisation that seeks to provide detailed access guides to thousands of venues across the UK, believes the key to change is better education. "As a disabled person and wheelchair user who likes to go to shows, I think there needs to be an education. That could be in the form of a campaign, featuring high profile disabled people saying theatre is for everybody, actually – and I want to be able to enjoy this," she says. "It's about bringing [outdated attitudes about theatre] into this century – in a way that the wider industry can get behind."

Lightley acknowledges that steps towards greater accessibility and inclusivity made by the Festival have been "fantastic." But she maintains that a truly accessible festival would see venues and companies giving "accessibility information as much importance and prominence as opening times and ticketing details," on flyers and posters as well as online and in the programme. "It's a case of: okay, I know where you are, and I know when you open – but do I know if I can get through the door?"