Apply Yourself: On phones, apps and grief

Phones get a bad rap for harming our mental health, but one writer explores how apps and social media can be harnessed for good

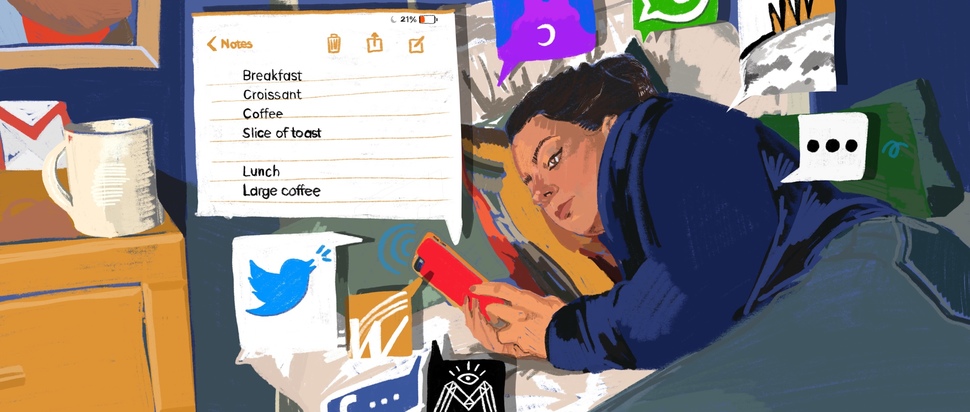

The first thing I should do when I wake up is meditate. But I don’t. Instead, I reach for my phone. Draw today’s Tarot card from Mystic Mondays. Do my best to decipher the cryptic poetry of Co-Star. Assess where I am in my cycle on Hormone Horoscope. Draft a pithy Tweet to post later if it’s as hot a take as I hope it is. Set my intentions or 'write my wins' for the day in WinStreak, while looking back on yesterday’s list to prove to myself that, yes, I am informed, I am inspired, I know I can survive today, I will dare to dream that I can thrive today.

I am a sensitive person with a history of mental illness. Needy, seeking external reassurance, often from less than healthy sources. But I did fall back on my mum because she made sure she was there for me. When I was in primary school, she had to commute, leaving the house long before I woke up. She would leave notes on my pillow, telling me to remember to take my swimming kit to school, to do my best to ignore the bullies, that she loved me. Once I moved out, she sent me an email every evening, part report of her day, part horoscope.

My mum died eight months ago. Losing her pillar of constant reassurance made me feel like a circus without a tent pole, flapping in the wind, full of wild animals on the loose. My friends and family are a solid, loving support network. They promised that I could call any time, that they were always there – but I knew that wouldn’t work on a pragmatic level. They have their own lives to lead. Besides, I have always been terrified of being too much, of becoming a burden. I knew I could lean on my friends and family but I didn’t want to crush them. I had to build my own scaffolding of solace.

There will never be a substitute for my mother. But I started to patch myself together again using the relatively new constant in my life: apps on my iPhone. Designed for attention and immediate response, I had a companion I could turn to at literally any time of day, that was incapable of finding me a drain on its resources. Well, so long as I kept the battery charged.

But am I doing myself more harm than good by turning to apps? Not being face to face with actual people, am I setting myself up for a cycle of addictive dopamine highs and cortisol spikes?

Fiona Thomas, author of Depression In a Digital Age: The Highs and Lows of Perfectionism, found that Instagram provided her with a lifeline to a community when she needed it the most. During a depressive episode, she could use Instagram to reach out to other people, sharing their lived experiences of mental health, when leaving the house seemed impossible.

“There just aren’t that many studies about the possible positive effects of social media on mental health,” she tells me over the phone. “It’s a powerful tool and there’s plenty of issues that shouldn’t be overlooked, but it’s not all bad, though you wouldn’t know from the widespread media coverage.”

One of the few surveys that does exist shows that 40% of British adults would seek online support through anonymous chat forums, phone apps and social media. The figure shoots up to 65% for 16-24 year olds who will typically turn to Google with symptoms or questions, with only 33% of that age group answering they would reach out to a mental health professional.

Is this a surprise when thousands of young people in crisis have to wait over a fortnight to access NHS mental health services? Online is always on. A screen can act as both a window and a barrier, which is perhaps a safer position to explore from than a doctor’s office, fearing judgement or dismissal.

However, in the current landscape of harmful content online, the darker side of social media can put vulnerable people even more at risk. Instagram was heavily criticised when it was implicated in the suicide of Molly Russell, who was 14 when she died in 2017, after viewing accounts that posted graphic material of self-harm through the platform. It is difficult to see in the face of such awful loss why this was allowed to be widely circulated, when photos of women’s nipples can be taken down in a matter of minutes.

The difference between protecting users from harmful material and censorship is hotly contested but little has been done to terms and conditions since Molly’s death in 2017. There is no shortage of gloomy statistics that connect heavy smartphone usage to the national rise of mental health issues. But do the figures reflect a causal link between social media and app usage and mental health issues or a surge in people able to get diagnoses precisely because of what they have learned and shared online?

“Putting that thought or feeling out there in a post and having it liked makes you feel recognised, even just by one or two people,” says Fiona, whose own Instagram profile has 3,700 followers. “You feel like you might be helping someone else too, by opening up.”

More mental health and bereavement specific apps are being developed, while Instagram accounts for organisations, like Let’s Talk About Loss, help young people access their services who wouldn’t necessarily attend an event without exposure to that publicity.

“The more you can hear that encouragement from a range of different sources, the more likely you’ll get that validation you need to get you through,” says Fiona. “If you’re only hearing it from your friends and family, your thoughts may tell you they’re just giving you lip service. When everyone you’re talking to is saying the same thing, it can help you believe that this will pass. You don’t have to worry about being a burden.”

My night time app routine is similar to my night time skincare routine – cleanse, slough, replenish. I fire up WinStreak to put in tomorrow’s goals. I scroll through Twitter to ensure I have enough nightmare fuel. I select a nature sound from Rain Rain, praying that 30 minutes is the right amount of Ocean Waves so that sleep can sneak in and take hold.

But I hear it fade out to silence. I’m having difficulty being at peace with what I ate, the plumes of my eating disorder threatening relapse after a good run of recovery. I used to send my mum an email with everything I’d eaten that day, granular amounts, including cups of tea. She’d reply quickly, pointing to this or that reason, that everything was alright, darling. I hover over MyFitnessPal. Get the hard data, crunch my self-worth into stats, make myself smaller, more manageable.

Opening my Notes app, my thumbs rattle out breakfast, snacks, lunch, more snacks, drinks. Looking at each entry resting on its grey line, almost like a real notebook, like the one on my bedside table, it doesn’t look so bad.

WinStreak, one last entry for the day. Soothed myself. Lights out.