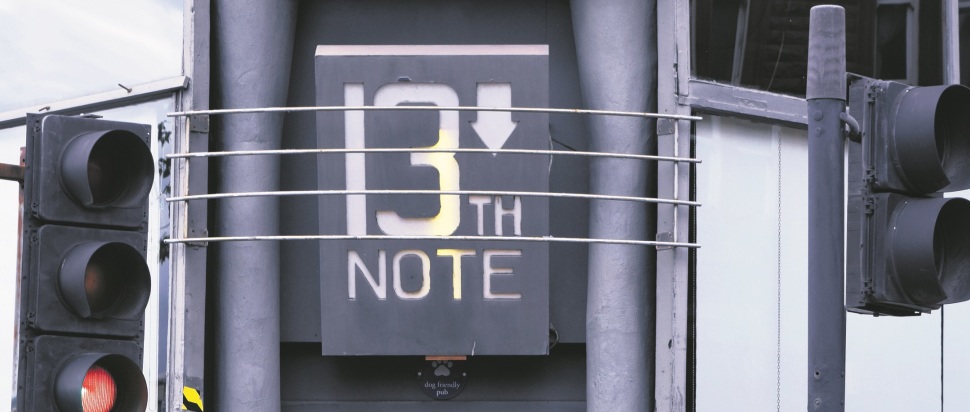

The 13th Note: What is a venue without its workers?

In light of its recent closure, to understand the legacy of The 13th Note we speak to a handful of musicians and workers who have passed through its doors over the years

What is a venue without its workers? Many in the Scottish music scene were asking this question about The 13th Note on Glasgow's King Street, long before the sudden announcement on 19 July by its owner Jacqueline Fennessy that it would close. The decision came in the middle of a protracted dispute with the majority of its staff over fair pay and improved working conditions which led to historic industrial action: the first strike by hospitality staff in Scotland in over 20 years. The closure brought the strike to an end just as it was getting going, signalling the loss of all staff members’ jobs, and of a venue that has a legacy for supporting underground and DIY acts since the 90s.

From its previous home on Glassford Street, where its music programming was once managed by Alex Kapranos, who would go on to front Franz Ferdinand, The 13th Note had a reputation for being a place that was affordable enough for fledgling acts to get a foot in the door, and well known enough for it to give them a decent rub. Seminal bands like The Delgados, Idlewild, and Mogwai played important early shows there.

The latter’s Stuart Braithwaite tells us: “We played our first gigs at The 13th Note and I’ve a lot of very fond memories of the venue. These venues that are outwith any kind of corporate music structure are really important. But even though it’s important these places exist for the cultural landscape, I also think that there can be a tendency for the owners of these places to take people who are invested in that for granted. People have a responsibility – it’s possible to run small venues attached to bars and cafes and treat everyone fairly.”

Michael Kasparis, who makes music as Apostille and worked at the venue at the turn of the millennium, reminisces: “I was a teenager at the time, full of idealism and excitement about working in a place that had already meant so much to me. I booked my first gig there in my first band. So, it was pretty cool to be working there, meeting and becoming friends with people who I admired and had done so much for a scene I was finding my feet in. It was an absolute riot working there – hedonistic, idealistic.

“The staff made that place happen back then and, from what I can see and know, continued to make it happen. Like us, they wanted to create a space where people could have transcendent experiences or feel welcome.”

Before its closure (its second, having gone into liquidation under previous owners in 2001), The 13th Note had been under scrutiny due to reports of a mouse infestation and outbreaks of mould. Staff had been asking for a living wage pay increase. The owner had refused to recognise Unite Hospitality for collective bargaining purposes despite 95 per cent of staff being in agreement.

In a widely circulated statement, Fennessy (who did not respond to our repeated requests for comment) blamed the closure on the impact of inflation and lockdown, but reserved the bulk for the way, she claimed, the representing union Unite Hospitality handled the labour dispute.

The union’s position painted a different picture. “To close a workplace and sack workers days after they take historic strike action is trade union intimidation, pure and simple,” Bryan Simpson, Unite Hospitality’s lead organiser, tells us. “To sack them with only a week’s wages and less than 30 days’ notice is also unlawful.

“Fennessy made a firm commitment to Unite and her workforce that she would postpone any redundancies until we’d at least had a chance to meet via ACAS to resolve the issue, a meeting that she called for.

“This employer didn’t even have the decency to tell some of her workers that they were being made redundant before she briefed the press with a smear campaign aimed at discrediting the workers who have made her profits over the years.”

We speak to employees of The 13th Note from over the years who give their position, which throws into question the value of legacy when workers are undervalued.

“There’s been zero respect for the artistic, cultural aspect of the matter, let alone those whose labour the owner profits from,” says Kay Logan, the venue manager and head engineer, who also makes music as Helena Celle and Free Musick. Logan also explains that essential equipment required to run the venue, such as the PA, was in need of updates and repairs. “What continued to be of importance to the city is that the venue was accessible due to its low hire fee, which remained low because you can't charge more when you're providing a substandard service at no fault of your workers. Any improvement would first require investment on behalf of ownership – you can't draw blood from a stone.

“The party line being pushed in Britain towards artistic endeavour is one that not only callously indicates that such matters are trivial, but that they should not be the purview of the working class. Nobody living off a part-time contract at a venue is living comfortably. I am from a traditional working-class background and without financially accessible venues such as The 13th Note, I would never have formed bands and be doing what I am doing today.

“Ultimately, it's about recognising that human aspect – are we here to make money, or are we here to make meaningful experiences? I think if your inclination is the former, then you're in the wrong industry for a start. If you create precarious conditions for your workers, and if the artists who play your venues are financially, functionally, or ethically unable to do so, then what happens to the culture? What happens to your venue if there's nobody to labour, and nobody to perform?

“Without workers, such venues are unable to function. It's why so many of them have such high turnover rates, and this is something that needs to change in the industry. We need to be fostering a culture wherein venues are not trading off performative ethics and tarnished legacies while simultaneously selling their workers down the river. If venues can't do this, what hope do they have of treating artists with respect? Arts venues manifest progressive political movements because those who truly labour for their benefit are doing so for something greater than financial reward – they are doing it for that which gives life meaning.”

With a crowdfunder on the go for the staff team, a solidarity gig at Audio scheduled, and an open letter from high profile musicians, there has been vocal support from across the spectrum. In mid-July, ahead of the first weekend of what was proposed to be a month-long strike, the queer, workers-owned cooperative Bonjour held a banner-making workshop.

But for a city awash with small, ostensibly progressive venues, according to Simpson “there is a clear disconnect between the huge solidarity that we were getting from the workforce of Glasgow's hospitality industry, customers and the music industry, compared to the owners of other venues who were perhaps unwilling to go on the record as supporting the first strike in Glasgow's hospitality history.”

That reality jibes with the idea that culturally significant spaces – places where progressive, creative ideas and thoughts germinate – are normally run by owners that share that stance. Is it important that these physical spaces are stewarded into the future in good hands?

“Since all of this happens within the framework of neoliberal capitalism, and it can’t be easy for venue managers and owners to maintain their bottom line, there is this thing of venues benefiting from leftist, DIY, punk rock credentials and catering to that sort of clientele whilst exploiting their workers at every turn,” one former employee, who worked there from 2003 to 2008 and asked for anonymity, says. “The 13th Note was the eye-opener for me on that front. I thought that working there would be egalitarian and fair-minded because that’s the politics of most of the events and people there, but the truth from the inside was the opposite.

“I wonder what these legacies are worth sometimes," they continue. "Just because a place has played host to wonderful cultural events doesn’t mean it wasn’t riddled with unfairness. Maybe DIY venues benefiting from radically-minded art should start publicly posting their working conditions so that punters can judge whether they are what they say they are in future.”

Simpson adds: “The 13th Note strike shows the divergence between the so-called ‘needs’ that owners have to make a profit, versus the workers who are still the lowest paid in the entire Scottish economy. The workforce of The 13th Note were simply collectively demanding a bigger slice of that pie. If a business cannot function while still paying the workers the real living wage, then it shouldn't be in business.

“Without the workforce, there is no venue," Simpson continues. "From the sound techs to the chefs, to the bar workers, they don't just feed and water the punters – without them there is no gig. And that’s why they deserve proper rates of pay, proper equipment and decent terms and conditions.

“The workers of The 13th Note made this venue, and they will be doing everything they can legally, politically and industrially, with the support of the union, to keep the venue going under workers’ control.”

Following strike action and a dispute with workers over contracts, safe working conditions, and a living wage, The 13th Note closed its doors on 19 July 2023

If you're financially able, you can support the 18 workers that lost their jobs via their crowdfunder: crowdfunder.co.uk/p/support-the-13th-note-workers