Archiving Palestinian sounds with The Majazz Project

Glasgow-based Palestinian sound artist Masa Nazzal speaks to Mo'min Swaitat from Majazz Project about the evolution of Palestinian music, and archiving as political resistance

Every month, as well as the usual weekly events round-ups, The Skinny Zap features a subscriber-exclusive essay or interview. Expect shenanigans, musings, and the usual best of local arts and culture straight to your inbox. Sign up to The Skinny Zap here.

This month, Glasgow-based Palestinian sound artist Masa Nazzal speaks to Mo'min Swaitat from Majazz Project about the history of the record label, the evolution of Palestinian music, and archiving as political resistance ahead of his event Archival Resistance at both the Glasgow Zine Festival and Embassy Gallery in Edinburgh.

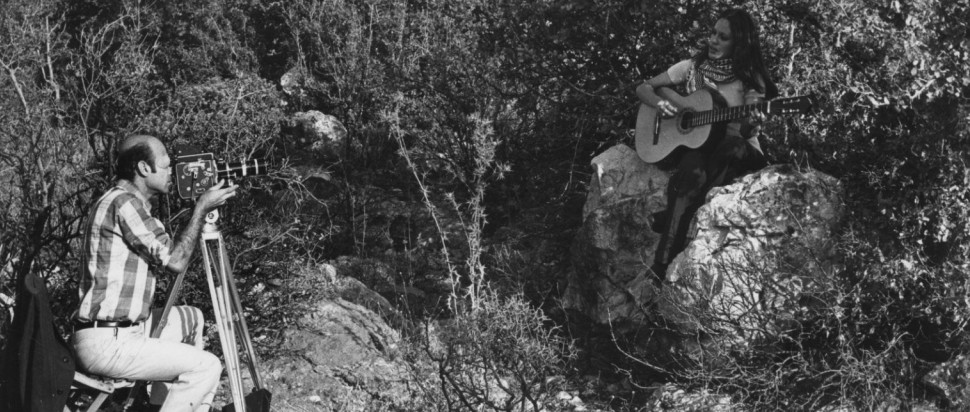

Photo of Palestinian musicians from the Majazz Project archive.

This week, in between cooking my Ramadan meal and working on my laptop, I hopped on a call with Mo’min Swaitat – a London-based Palestinian artist who specialises in theatre, playwriting, filmmaking and archiving – to talk to him about his incredible archival record label and research platform Majazz Project.

Majazz Project started in 2019, on a trip to Swaitat’s family home in Jenin. Going through old records in search of hordes of Palestinian-Bedouin music, Swaitat slowly went through his family’s music archive, listening to and transporting himself to different emotions and spaces from a collective Palestinian past.

While doing this research, Swaitat had a flashback to a small record and cassette shop next to the primary school he attended when growing up in Jenin. After discovering it had closed in the subsequent years, he called the previous shop owner, Tarrek, who still had access to thousands of physical copies of Palestinian music that had not been heard in decades, from old released music to pieces that Tarrek himself had recorded and self-releases on cassette. Tarrek’s treasure trove was an endless source of Palestinian musical history – live recording of bands, field recordings from weddings, numerous untitled cassettes – preserved yet unknown until this moment.

Swaitat spent six months exploring the collection, out of which was born The Majazz Project. Swaitat’s vision was to bring these Palestinian sounds to the outside world – to Palestinians in the diaspora and the Arab world, and those living in the West Bank and Gaza – creating a space for these left behind and abandoned sounds and giving them new life through digital and physical reissues.

Ahead of Swaitat’s upcoming event at the Glasgow Zine Festival taking place on 4 May at the CCA, I sat down to talk to him about the power of archival work, Palestinian resistance, and the celebratory potential of music.

Nazzal: This archiving feels like a form of connection, whether through the vinyl or cassettes that you found or by mixing and re-releasing them. Especially in Palestine, where we live in fragments all over the Middle East, the world, and even all over Palestine, archiving feels like a way to bridge that fragmentation. It's a form of re-education for culture that has been lost.

Swaitat: 100% I agree, and I want to add to this. This collection had multiple underlying connections. The thing about Palestinian music is that it sounds completely different from Syrian, Lebanese, or Egyptian music because of the political situation that the Palestinian community lives in. We have electronic, psychedelic, kinda Bedouin, dabke music that grew in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

If you go back to the 1930s, Palestinian music was similar to Egyptian or other Levant music. Yes, there was still the British invasion in that time, but they were not planning to hijack culture, music, foods or ways of living. But Zionism was to hijack all of this... if you listen to Palestinian music after 1948 it tells you everything, you can tell the dramatic shift in Palestinian sounds that accompanied Palestinian culture. Even today, if you listen to independent Palestinian artists, their music 100% embodies what is happening today in Palestine.

Nazzal: Definitely. Palestinian music has always embodied resistance through sounds of joy and celebration. Your archiving work shows that as well: how much people are able to dance and celebrate their resistance.

Swaitat: By the time of the Second Intifada, Palestinian music developed its own authentic sound, a revolutionary sound. It doesn't mean that this sound can’t be played in public or on the dance floor. My research is here, in the struggle between how we can celebrate our culture without attaching it to the reality of the settler colonial project. If you listen to Palestinian music, you can celebrate. The majority of The Majazz Project is celebrating and resisting.

Nazzal: Music and sound within Palestinian culture and within our struggle for liberation has been the very essence that invigorates our fight. Do you think that relationship with music has changed or transformed after 7 October and the ongoing genocide happening in Gaza?

Swaitat: Firstly, I don't want to feed into the Israeli narrative that all of this started on 7 October because it didn’t. But yes, everything has changed since that date, not only the Palestinian sound. I look at music events through a different lens, I look at DJs through a different lens, I look at dance floors through a different lens. I can’t see people playing dance music and club music and chanting “Free Palestine”. This is not going to work.

Nazzal: It's completely performative.

Swaitat: I just don’t get it. I don’t get people doing club nights for Palestine, but not playing any Palestinian celebration music. People stopped knowing how to position themselves in this situation. But you need to listen to Palestinians with lived experience, either inside Palestine or in the diaspora.

Nazzal: A lot of what I find now in Scotland is people speaking solidarity without acting in solidarity. They need to learn what it means to resist alongside Palestinians.

Swaitat: I agree with you. I don’t think they need to put themselves in a solidarity position, because in a solidarity position it means you are not 100% involved. The sad news is everyone is involved. So we need to rethink and reframe solidarity with the Palestinian cause.

Archival Resistance takes place at CCA, Glasgow, 4 May at 1pm and at Embassy Gallery, Edinburgh, 5 May at 5pm; tickets available via Glasgow Zine Library and Sumud Edinburgh, all ticket sales will be donated to the Majazz Project.