Fiddlers On the High Seas: The history of Scottish fiddle music

As a sea shanty tops the UK charts in 2021, we take a deep dive into the history of Scottish fiddle music via the stories of Shetland whalers and Orcadian fur traders who harnessed creativity in isolation at sea, taking their influence across the Atlantic

An old woman was once walking along the coast of Unst, the northernmost of the Shetland Islands, when she spotted the figure of a man lying on the beach. He was a German sailor, washed up after having been thrown overboard by his crew for ceaselessly playing his fiddle, which he clutched even in his unconscious state. His name was Friedemann von Stickle, and he was – well, a fiddler. Following his recovery at the old woman’s home, he started a family, remained in Shetland till the end of his days, and played the fiddle on most of them.

Or so the story goes. But more well-known is his son, also named Friedemann, whose fiddle tunes rose to legendary stature in the Shetland archipelago. He was the father of Robert Stickle and grandfather of the famous fiddler John Stickle. In his lifetime, Friedemann was considered the greatest fiddler in all of Shetland, but this was not without its perils: in his adulthood, he was supposedly forced on board a ship and taken to sea, tasked only with playing the fiddle to the crew in the mess room. All the generations of the Stickle family certainly contributed to Shetland’s musical tradition enormously, but it was Friedemann alone who participated (against his will) in one of the most interesting episodes in the history of Scottish music: the great maritime adventure of the fiddle.

The Shetland and Orkney Islands are conveniently located on the nautical routes of ships entering and exiting the North Sea. The fiddle was first brought to Shetland by Hanseatic traders in the early 1700s and soon found its way to the mainland, becoming an integral instrument in traditional Scottish music. The fiddle has been from the very beginning an instrument at sea. It was certainly the most common one on board any vessel in the north. The Shetland and Orkney Islands were both responsible for catapulting it across the Atlantic – but to understand this small, portable instrument, one must first understand the whale, or rather, the men who hunted it.

In the 164 years between 1750 and World War I, Scottish whalers returned with the blubber of over 20,000 whales and four million seals. While these figures evoke an image of large-scale, relentless butchery, whaling expeditions were for the most part spent in uneventful waiting, and consequently, extreme boredom, which made these voyages perfectly placed for the making of music and art, all in a blur of sea salt and blubber. Shetlanders were also most suited for whaling; they were traditionally fishermen and seamen and provided cheaper labour than mainlanders. So the men left for the Arctic, taking with them their beloved fiddle.

Whaling soon became the defining occupation of the Shetland Islands, which sent men to far-off corners of Greenland and the Northwest Passage. Maurice Henderson, a well-known musician from Lerwick, suggests that the industry became inextricably linked with social mobility, breaking away from the feudal-style Haaf fishing system in Shetland. “The way the system worked with Haaf fishing was that you fished for the merchant-lairds, and you gave all your fish away to them. It was only at the end of the season you were allowed to fish for yourselves. Everything was tied down here. So, if you went to Greenland, you certainly made some independent income coming in and it didn’t go down well with landowners. A lot of folk were threatened with eviction if they didn’t give up the whaling.” It was with whaling that Shetlanders were finally able to acquire their own boats and buy out their freedom.

But Shetlanders took on all manner of other marine occupations, too, some in the fishing industry and others in the Merchant Navy. One example is the prominent fiddler Gilbert ‘Gibby’ Gray, whose service in the Merchant Navy landed him in the maelstrom of World War II. He was the grandfather of Scottish fiddle player Vicky Gray. Released at the end of March, Gray’s debut EP Atlaness draws on traditional fiddle tunes played by her grandfather while bringing in newer approaches to record production. “Shetland reels are very short: some of them are only 16 bars long!” Gray explains. “You’ve got the tune, but a big part of the entertainment is telling stories that go with the tune and being a bit of a comedian, trying to make people laugh and have a good time.”

The history knitted into Shetland’s music is still imparted today, not only through tunes but also material culture. “A couple of summers ago, when I was in Shetland, somebody loaned me a fiddle that was made out of metal,” she says. “Because wooden fiddles would disintegrate when people were away at sea, it was quite common to have these fiddles that were made out of metal.”

Shetland’s fiddle music is only one example of a rich oral tradition that has historically pervaded all of Scotland. Gray tells us: “Because of the limitations of writing something down, you turn it into something different. In Shetland, there’s tunes where they would play a note that’s in between C and a C#, for example. So, they didn’t stick to a normal scale.” Much of the music’s vibrancy is impossible to capture on paper. But, once again, it was completely suited to whalers with nothing but time on their hands and wits sharper than harpoons.

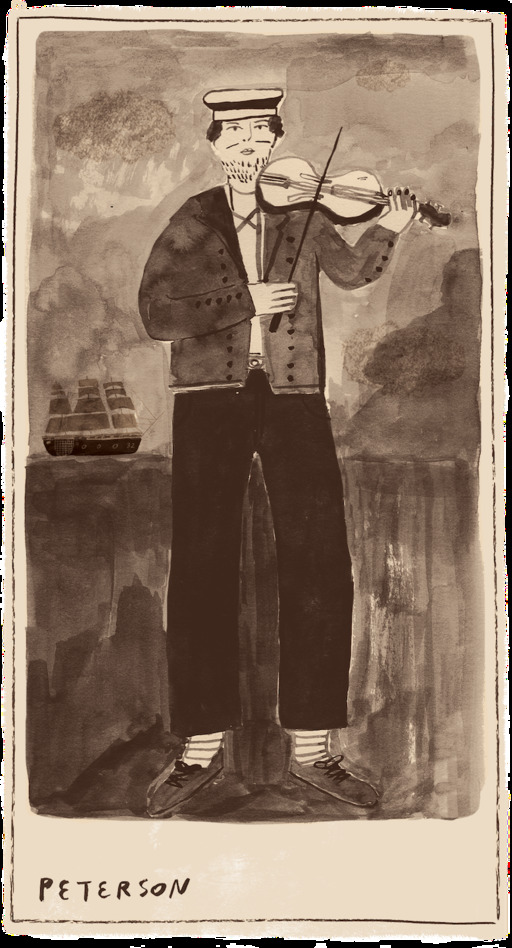

Sailors who doubled up as fiddlers were especially valuable to a whaling company for sustaining the morale of the crew. But to the historian and musician, they are valuable for the music they created at sea, much of which is still part of the Shetland repertoire. The widely popular reel Willafjord, for instance, was brought home by fiddler Bobby Peterson’s father after a voyage to the Davis Strait. The tune hints at a near-mythic location hidden in the then-unmapped Northwest Passage. Henderson actually visited the eponymous town in Greenland, and chronicled his finds in his book In Search of Willafjord. Similarly, Ollefjord Jack (sometimes called Oliver Jack) is probably named after the coastal village of Olderfjord in Norway. Both tunes not only bring Norse influence into the Shetland repertoire, but also reveal a musical map of Shetland whalers’ journey through the ice.

The Shetland repertoire is incredibly diverse, ranging from ceremonial tunes, wedding tunes, Christmas tunes, 'Trowie' tunes, and among them, from a particular time and place in Shetland’s history, are the Greenland tunes (or 'whaling' tunes). Many of these tunes are vignettes of a period of intense economic and cultural production in Scotland and at sea. The opening lines to Da Merry Boys o' Greenland, for instance, strikingly describe the call of the sea – the search for wealth and adventure that Shetlanders embarked on when sailing to the Arctic: 'Da news is spreadin trowe da toon / A ship is lyin in Bressa Soond / Tell da boys shö's nortward boond / Ta hunt da whale in Greenland'.

There, tunes developed by seaborne fiddlers were enriched by the musical and cultural exchanges between mainland Scots, Shetlanders, Hollanders, Norwegians, and Irishmen, who fiercely competed to prove the superiority of their own tunes. The development of fiddle tunes on these ships is testament to the salutary effect of the confluence of cultures and identities. The ships became crucibles of experimentation and evolution, as laden with musical innovation as with whale blubber. Perhaps what is special here is the improbability of the backdrop to this artistic production: the frozen-over, desolate northern waters, a far cry from any comfortably situated concert hall or art studio. Such encounters between different musical traditions allowed unique tunes to find their way back to Shetland, mostly dealing with nautical themes and with fragments of the world embedded within them.

Cultural exchange was not limited to Europeans alone, however, and the fiddle, helplessly afloat on the icy seas, did not simply venture out and return home like the men that played it. The greatest lasting impact of the Shetland fiddlers has been on the Inuit population of the polar region. The Inuit of Greenland traditionally performed throat songs and drum dances, but these were later joined by European instruments like the fiddle, whose tunes are still popular in Greenland today.

“There are actually documented accounts of Shetlanders going ashore,” Henderson tells us of whalers in Greenland, “and if you were a fiddler and they found out you played the fiddle, you would have a hard time getting away. You would be dragged into the dance for playing.”

Although the three whaling tunes discussed above were brought home by Shetlanders out on voyages and had no indigenous influences, many musical pieces from this period appear to be Inuit, or ‘Yakki’ tunes, the only two surviving ones being the listening tune Da Greenland Man’s Tune and the reel Hjogrovaltar. Dr Frances Wilkins, an ethnomusicologist and lecturer at the Elphinstone Institute at the University of Aberdeen, has done extensive and fascinating research on Scottish ‘musical migration’, and suggests that both tunes possibly contained Inuit words. She argues that, while it is believed that ‘Yakki’ tunes were written by fiddlers too modest to claim authorship, the numerous historical references to indigenous fiddlers indicate a two-way exchange of fiddle tunes between Inuit and whalers.

In his book In Search of Willafjord, Henderson expands on his encounters with Inuit music along the way. He finds the fundamentals of Inuit song and dance astonishingly similar to what he experienced and performed back home. “There are definitely similarities [with Shetland tunes] in the sense of the type of music, and the dancing as well,” he says. “Just look at the form of the dance, whether it’s a round-the-room couple dance or a set dance, like a Shetland reel, or a step dance, or a figure-of-eight formation. Where I went, I saw that they do a lot of polka dances, and it’s really high-energy music, very similar to Scottish dancing. There are similarities, but I wouldn’t say they would know our tunes exactly and we’d know theirs.” He adds with a laugh, “But it wouldn’t take long to learn them or join in.”

The integration of the fiddle into indigenous musical traditions is by no means limited to Greenland. And here, the music historian must tear her riveted eye from Shetland to Orkney, and from Greenland to James Bay, Canada. Operating at the same time as the many whalers in the Arctic were the fur traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company. At one point, four out of five company servants were Orcadians. Much like Shetlanders in whaling, men from Orkney dominated the Canadian fur trade, partly because of their cheaper labour and excellent seamanship, and partly because it was the last port of call for ships sailing from London to Canada. The earliest fur trading posts were established around James Bay, where Europeans could trade with the local Cree population, who were soon incorporated into the cultural lives of the traders.

Dr Wilkins observes that there is no evidence of any stringed instruments used in James Bay before the arrival of Europeans. The Cree musical tradition mainly comprised hunting songs accompanied by drums and rattles. Dr Wilkins writes that, “by the late 1800s the James Bay Cree along with other Aboriginal and Métis groups in northwestern Canada, northern Ontario and northern Québec, had developed an identifiable ‘Aboriginal/Métis’ fiddle tradition.” James Bay became home to a mishmash of musical traditions, old and new: the fiddle was accompanied by the drum, and British square dancing with indigenous step dancing.

Dr Wilkins admits that much of the historical research available is shaped by colonial prejudice, and there are certainly discrepancies between indigenous and Western sources. It would be wrong to ignore the role of missionaries in discouraging the use of drums among the Cree population and settlers’ attempts to subsume native traditions under a broader European musical culture. Nonetheless, this does not take away from the extensive reach of these tunes. Indigenous communities have long cherished and innovated fiddle music, and the accompanying dance forms, like square dancing, which is still performed in Canada today as far north as Pond Inlet and Baker Lake in Nunavut.

The last ship bound for James Bay sailed out of Orkney in 1891 and brought an end to the period of intense mixing between Orcadians and Cree. Arctic whaling also finally ended in the 1900s, and South Georgia (a remote island southeast of the Falklands) became the new haunt of Shetland’s whalers. It was a new age for the fiddle, now influenced by country music, played alongside the guitar and accordion, and heard far and wide on the radio.

Aidan O’Rourke, a fiddle player and composer of Scottish folk music, offers an insight on the 'Scottishness' of music that travelled to places like Cape Breton, Canada: “If you go to Cape Breton, you hear a version of the music that would have been played here before Scotland became this tartan entity.” Scottish musicians who listen to indigenous fiddlers often admire their less formal, more fluid style, that fiddle players like Gray find it so difficult to translate into writing.

The fiddlers at sea were perhaps the farthest thing from the dissemination of music today. It is mere clicks away, available for mass consumption and usually made for large audiences, like sea shanties on TikTok. O’Rourke wonders whether anything like the long-lasting and profound cultural imprint of the fiddle can ever be replicated today. “I just think that if there’s enough exchange of people anywhere, music fits into it. Maybe we’ve lost that… That direct exchange, a human exchange, which can happen instantly on the internet – the actual importance of that face-to-face exchange and the nuances built into that.”

During the pandemic, geographical boundaries have been replaced by self-imposed, invisible ones, and the newest challenge is to touch upon the local rather than the remote. O’Rourke himself has replaced concert halls for his own backyard, where his neighbours may listen to him, not out of necessity but of a newfound regard for his immediate surroundings. Both he and Gray hope that a post-lockdown approach to music will take place in smaller, more inclusive spaces that connect people more intimately.

Art has often been created in the unlikeliest of places, far from the clutches of formal education and 'civilised' practices. The Arctic is one such place, whose utter desolation gives no sign of any inspiration for musical creativity. And yet, the fiddle braved these odds and won. One could say that an isolated flat is perhaps an unlikelier place for any sort of artistic endeavour than a whaling ship. We are, perhaps, in a time unlikelier than any other for creativity. Yet it is to be hoped that we seek out the same entertainment once sought by Shetlanders and Orcadians navigating the ice. As is evident in our histories, tunes, and dances, the only known panacea to human suffering is the human spirit. And perhaps a fiddle to cheer it up.

Maurice Henderson's In Search of Willafjord is out now via Shetland Times Ltd

Vicky Gray's Atlaness is out now via Stitch Records

Aidan O'Rourke's The Best of 365 is out now via Reveal Records; the film Iorram (Boat Song), which he wrote the score for, premiered last month at the Glasgow Film Festival

This article was produced with support from Edinburgh International Festival

Follow Armaan on Twitter @armaan465

Illustrations by Maisy Summer Lewin-Sanderson