Watching the news as a second-generation Iranian immigrant

2020 started with the US assassination of Qassem Soleimani, throwing Iran into turmoil and causing World War III to trend on Twitter. Here's what watching the news unfold felt like to this second-generation Iranian immigrant

I spent the third day of this new decade on a train to Edinburgh, staring blankly out of a window and constantly refreshing the news on my phone. In the early hours of that morning, Qassem Soleimani, the Islamic Republic’s leading military figure and the most powerful person in Iran after Ayatollah Khamenei, had been killed in an illegal drone attack in Iraq on Donald Trump’s orders. Iran had vowed retribution, Trump was reacting in a classically deranged manner and World War III was ghoulishly trending on Twitter. As a second-generation Iranian, all I could feel was a numb kind of panic.

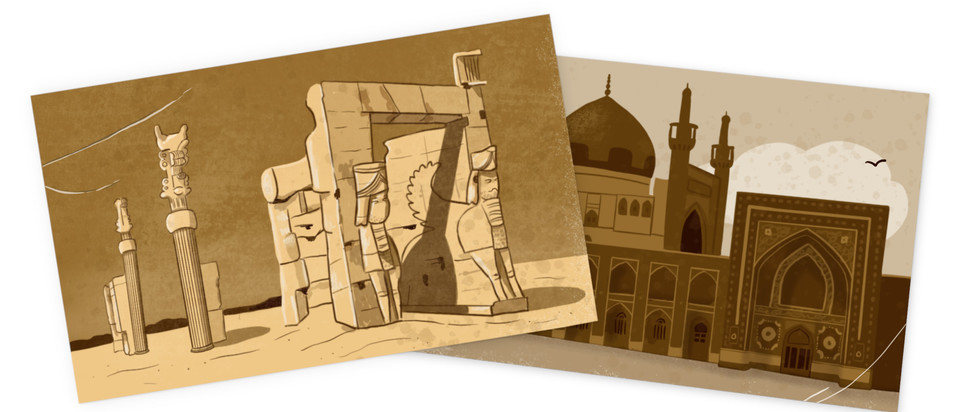

As second-generation immigrants go, I’ve mostly been isolated from my ‘home’ country. I don’t have dual citizenship, my language skills are largely confined to the level of family gossip and I’ve never even set foot in Iran. Instead, I’ve tended to experience my inherited culture through fragments and residues that keep me tentatively anchored to a place I have never been, but still feel intrinsically bound to: anecdotes and reminiscences from family, old photographs of Persepolis that my grandfather took in his student days, signs translated into Farsi in NHS waiting rooms.

“That person is Iranian,” I exclaim triumphantly to friends who are a little nonplussed as to why I’m blurting out random facts about passers-by. “Ottessa Moshfegh sounds like an Iranian name,” I say firmly, smug when I’m proven right. They’re very small things, but they are mostly what I have, keeping me moored to the culture in its broadest, most rhizomatic sense, fostering a minimal sense of belonging.

In this way, home – the ancestral idea of it – has become a kind of imagined place, experienced purely through second-hand construction. The connection I have with Iran feels tenuous, gossamer-thin and constantly on the brink of dissolution, yet, simultaneously, firm, undeniable and entrenched in my very identity. It’s a particularly second-generation experience – caught between belonging and not belonging – and one that is utterly bewildering in times of crisis such as these.

When Trump threatened to destroy Iran’s cultural sites if the country dared to retaliate, it felt intolerably violent even though, at the time of writing this, it has remained a verbal threat. Disgusting as his proclamations typically are, these were personal and felt surreally, horrendously abusive. Of course, second-generation immigrants such as me, thousands of miles away from the physical land and – in my case – protected in a comfortable middle-class life, will suffer the least if military conflict unfolds. Yet we remain entangled with the place and its people, if only through the imagination, and the intimidation of such brutality is still unbearable.

Carol Isaacs’ graphic novel The Wolf of Baghdad explores the exile of Iraqi Jews from Baghdad and lingers on the untranslatable Finnish word kaukokaipuu, meaning homesickness for a place you’ve never been. How I feel is a type of homesickness, but it is also more. It’s a compulsive and uncanny recognition despite almost no mutual experience or physical proximity. I am so far down the list of people affected by this potential violence and loss in their quotidian lives. But I still feel bound to it.

Of course, this impending sense of dread is not abated by historical perspective. There is a totality to Western violence in the Middle East that is sometimes too vast to comprehend. Estimates of casualties during the Iraq War vary from 100,000 to well over a million, while entire swathes of Syria have been razed to the ground. Millions of people have been displaced, many of them drowned in the Mediterranean as Europe frantically began to close its borders.

Although the response to Trump’s assassination of Soleimani was largely negative, it was frequently filtered through a fear of Iranian retribution and concern for American military lives. From both the political right and left, little attention was paid to Iran’s people, its infrastructure and the potential collapse of an entire cultural group. The West, as usual, conveniently forgot that the main victims of Soleimani and the brutal regime were Iranian citizens.

At the time of writing this, the mounting tension seems to have somewhat abated – at least on Twitter, a sentence almost too absurd to type – but new sanctions have been enforced, Iran is resuming its nuclear programme and there are demonstrations flooding the streets of the country. Iran still feels like it is teetering on an edge, caught in the push and pull of Western imperialist megalomania and the atrocities of its own autocratic regime, deeply vulnerable to both. And while my experience of the country has always been predominantly imaginary, the anxiety I feel is emphatically concrete. It’s the anxiety that second-generation immigrants know all too well, trapped in the liminal experience of attachment and exile, gazing across a gulf of continents, generations and familiarity, fearfully looking on.