Mind & Matter: Scottish mental health and the arts

What does a mental health revolution look like? We chat to the artists and academics of Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival's Manifesto event about community care, government support, and questions with no answers

There’s a large chasm of understanding between ‘mental health’ in current discourse, often reduced to social media hashtags, self-care tips, and exercise suggestions, and the concrete actions necessary to address mental health issues. This divide – marked by long waitlists, misunderstandings, and political and economic upheaval – signals an opportunity for change.

The Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival is embracing the need for change with the idea of a mental health revolution. The festival launches on 4 October with Manifesto – a day of future-facing events at Glasgow’s CCA, calling on participants, artists, and activists to unite and collectively create a manifesto for social change.

“I think we’re very good at talking but we don’t get out there and physically do something,” begins Heather Marshall, an activist and performance artist, hosting a day-long communal installation. For Marshall, her interest in acts of revolution was partially sparked by research into the 1987 Barlinnie Prison Riots, led by one of her relatives. The very act of taking to the roof in protest of their conditions triggered a curiosity and sparked the title of her play and Manifesto session, She’s on the Roof. “I want to speak to people about what they care enough to protest about.”

Marshall’s work is often community-based, meshing art with activism and her passion surrounding mental health. Tape art, particularly, has become an effective medium – taping often brightly coloured words or phrases to buildings and communal spaces; designed to stimulate the observer. The aftermath of the murder of Sarah Everard saw Marshall tape a scored-through ‘Protect Your Daughters’ followed by an emphasised ‘Educate Your Sons’ across an empty storefront on Princes Street. She was then jumped by young men in balaclavas, who stole her equipment and bag. “I had to make a quick decision. I could panic or I could stay calm and use my youth work skills,” says Marshall. “I stayed calm. I chatted to the boys. They apologised and gave me my bag back. We spoke about tape art, I gave them some tape and they taped up what they felt passionate about.

“These young men were only 14 or 15 years old. They were bored and angry. They’d been out of school for so long because of the pandemic and youth services had shut down. They had nowhere to go, and nobody listened to them. I like talking to people. I like hearing their experiences,” she continues. “And I think often we don't hear people's voices unless they are the privileged few.”

Marshall notes that the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) waiting list is four years long in some areas. “It’s such a problem that a service was set up to support the young people on the waiting lists,” she says. “We’re constantly seeing Westminster making cuts to the NHS and it’s the poorest in society that are suffering from that.”

Hosting an interactive discussion at Manifesto, Dr. Matthew Smith, a Professor of Health History at the University of Strathclyde, is also deeply interested in this link between socioeconomic factors and mental health. “My work demonstrates that for nearly 100 years, researchers have been investigating the links between socioeconomic factors and mental health,” he begins. “And time and time again, the evidence demonstrates that these are some of the most significant factors. Not only in causing mental illness, but also exacerbating mental illness.”

Smith’s focus primarily lies on the potential of Universal Basic Income (UBI), a guaranteed income that everyone unconditionally receives throughout their life, to ensure no one falls below the poverty line. Smith believes it to be the “best policy” to confront poverty, inequality, and social isolation and disintegration. “If you’re tackling those three or four social problems, you’re also going to prevent a lot of mental illness and existing mental illness from getting worse,” he explains. Smith is keen to highlight the financial barriers surrounding often-applied wellness advice. “Money dictates whether you can go for a walk and where you’ll go for a walk. If you’re stuck in a high rise somewhere and there’s not much around that’s very pretty, going out for a walk might not do much for your mental health.”

Smith points out that UBI was raised as a possibility during the pandemic, and four out of five main political parties had UBI in their manifesto during the most recent Holyrood elections. It is a viable option, but it’s often forgotten and disregarded. “Mental health is extraordinarily complex,” he says. “There are no ‘one size fits all’ solutions when it comes to mental health but – on the other hand – there are big things that we can do that make a big impact.”

It’s key that we reflect: on our past, present, and future. “The more people start to think about how things could be better and how things could be different – it empowers us to make those sorts of changes,” he says. “History is important here, because history tells us things don’t just happen. We have the power to make changes if we want to.”

Such reflection on the past is also at the centre of the work of Skye Loneragan, a writer, performer, and theatre director, also contributing to Manifesto. Her work-in-progress sharing, May Contain Nuts (*), is full of what Loneragan affectionately deems "hot potatoes" – fictionalised interpretations of controversial or challenging situations, often inspired by true events. A television commissioner requesting a psychiatrist ‘sign off’ on her representation of her father’s schizophrenia; a journalist questioning whether a family member had consented to their loose inspiration of a character in a previous work; a sensitivity reader scrutinising her previous play’s suitability. Loneragan teeters between reality and fiction, the serious and absurd.

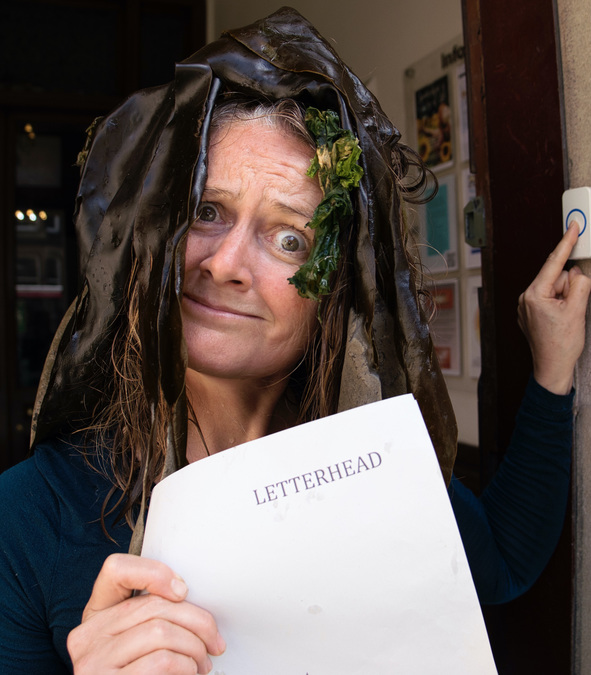

Skye Loneragan. Photo: Roddy Simpson

Loneragan’s work interrogates concepts like ‘Lived Experience’, by personifying and exploring their very existence. What is Unlived Experience? Is Lived Experience simply a pseudonym for Anything Out of the Ordinary? “We can question something at the same time as pointing out the ridiculousness we end up in with the stigma that’s involved,” says Loneragan. And, crucially, there’s real power in doing so with others who understand mental illness, first-hand. “Often I feel like – if you could just talk to someone who understood the territory, then you’d get a short circuit through to ways of coping.”

“What I’m trying to write about is provocative. It isn’t an answer, it’s a question. That’s how I feel I can contribute to the wider idea of transformation,” she says. “My intention is that we get to have a disturbing giggle. Ideally, I hope people walk away feeling less alone.”

And there is, certainly, a glimmer of hope. Marshall admires the growing representation in the media, especially for the younger generation, with shows like Heartstopper igniting discussion around gender and sexuality. And, closer to home, “I think it’s nice to see more arts activities taking place in local communities. It’s just trying to find them and ensure that they keep happening.”

“I think in particular, artists have to spend so much time doing crappy jobs when they really want to be making their art,” Smith empathises. He speaks of a talented cousin in Canada, forced to end his pursuit of a music career due to a lack of financial income. “There’s a UBI pilot going on in Ireland where they’re focusing on artists. I’m really interested to see what happens as a result of that; how it changes their ability to create. Had my cousin had access to UBI, there’s no doubt in my mind he’d be able to make a go of it.” There’s a lot of possibility and potential – in Scotland and further afield.

Changes have been made; and it's a step in the right direction. There’s a shift in understanding towards the mental health of men and increased support available from organisations like Men Matter Scotland and Brothers in Arms. Hope Point, a new 24-hour crisis centre, has opened in Dundee, providing support to those who need it, without the need for a GP referral. And after an independent review into Scotland’s Mental Health Law, the Scottish Government acknowledged that they will reassess legislation to ensure it ‘leads the way’.

But it’s not enough. What does a mental health revolution look like? And how do we start one?

As a queer, disabled, working-class person, Marshall acknowledges that it can feel like “shouting into a void.” The solution? A gentle revolution. “One where we look after ourselves and we build our strength up, so we can join that larger revolution and ensure that there is funding and safe spaces and all that we need as a community to look after our mental health.” Perhaps the revolution must see us unite and put into practice what we need from policy.

“We often hear about mental health. That’s not enough,” Smith adds, “We need to talk about what causes mental illness – and when those causes are socio-economic in nature, we need to take the next step and do something about it. We’re living in a society that’s very unequal, and we need to do something about it.”

For Loneragan, joyful provocation is necessary to ignite change. “Somehow curiosity and contentiousness have to sit together.” Later, she adds, “Or curiosity with compassionate approaches to what is contentious… I think I have more questions than answers!”

Undeniably, it’s in this ambiguity – the gulf between reality and potential – that the mental health revolution exists. Solidarity and support propels the campaign for a fairer future for everyone in Scotland – from Manifesto to beyond.

Scottish Mental Health Arts Festival runs from 4-22 Oct across Scotland

Manifesto, their opening day of events, takes place on 4 Oct at CCA, Glasgow

More information & tickets available at mhfestival.com