The Unheroic Journey: Awards Season's Best Biopics

Narrative fiction has long travelled outwith the rigid story structures set out by Aristotle and Joseph Campbell, but biographical cinema has been slow to catch up. Might this year's crop of biopics be turning the tide?

Awards Season is in full swing. It’s a time of red carpets, chaotic speeches, post-show celebrity sightings, and an overrepresentation of biopics. This genre is perennial awards fodder: the subjects are known and recreating the past an art unto itself. The best allow a humanising glimpse into deified or vilified subjects through cinema’s narrative and imaginative possibilities; the worst rely on subject matter alone to earn accolades.

In 2000, Roger Ebert described biopics as fundamentally simplifying – they “see the good in a man and demonize his enemies… If they didn’t, we wouldn’t pay to see them.” Ebert underestimates the human thirst for the messy, weird, and unwise. Transposing a life onto a conventional Western story structure is a fundamental genre problem, but the issue is less Aristotle’s three acts or Freytag’s pyramid than sending a real figure on Campbell’s hero’s journey.

Through studies of world myths and Jungian training, American writer Joseph Campbell based the “monomyth” – the “universal” story – around an exceptional protagonist. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he describes the “hero’s adventure”: leaving the everyday for a heightened world; overcoming tests and trials, often with a mentor; facing a final ordeal; and, if not dead, returning with a “boon” for those he left behind. Sci-fi and fantasy fans may be most familiar with this – George Lucas explicitly credited Campbell for inspiring Star Wars – but biopics are not exempt. Treating Campbell’s journey as a shorthand for truth and universality exaggerates focus on the individual and can make the larger-than-life appeal of 'great' figures ring oddly hollow.

Walk the Line is the quintessential Campbellian biopic; flashbacks build to Johnny Cash’s performance at Folsom State Prison, seeing his rise from the ordinary to the extraordinary via trials (largely of his own making). The 'boons' are his artistry. Despite bravura star performances and meticulous reconstruction of time and place, Walk the Line's formulaic structure spawned the greatest lampoon in cinema: Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story.

The half-life of recent biopics feels short. Have you thought about The Theory of Everything, Darkest Hour or Judy since their Oscar wins? Probably not. Perhaps these biopics' tendency towards tidiness is to blame. Think of Maggie Nelson’s refutation of Joan Didion in The Red Parts: “Stories may enable us to live, but they also trap us… In their scramble to make sense of nonsensical things, they distort, codify, blame, aggrandise, restrict, omit, betray, mythologise...” The film industry has struggled to sell a life without an embedded hero’s journey, but as these limitations become known the tide may be turning. The biopics of the 2024 awards season are varied – some hewing close to formula (Rustin), some doing away with it imperfectly (Maestro), and three proving illuminating across the spectrum.

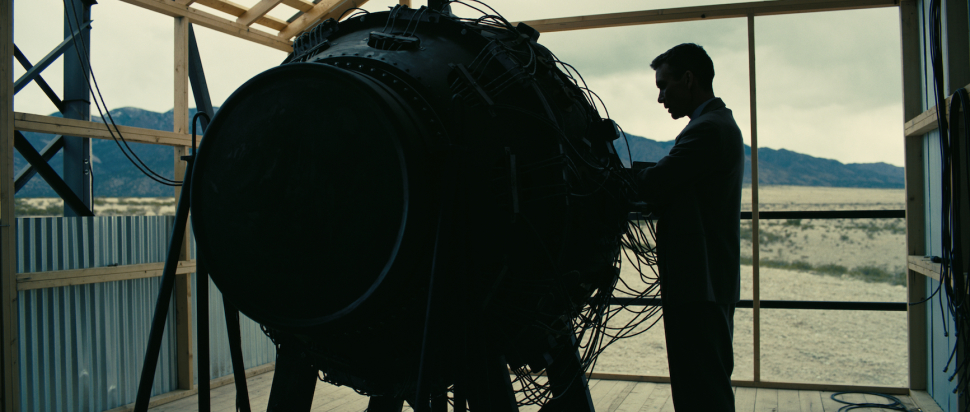

Oppenheimer, Napoleon and Ferrari

Considering Christopher Nolan drew from American Prometheus, a J. Robert Oppenheimer biography explicitly invoking the mythic titan who gave man fire and was forever punished, a Campbellian slant in Oppenheimer is unsurprising. Despite the interlocking narratives (one titled 'Fission', the other 'Fusion'), the film does little new with the genre. While the narrative of 'Fission' continually comes back to a McCarthyist deposition, Nolan cannot avoid the Campbellian compression of a life from student hardships through to scientific and moral reckonings to old age to fuel each point of interrogation. Mentors, temptations, clashes, and achievements of the previously impossible appear in succession. Meanwhile, 'Fusion', the more interesting section, turns the attempted cabinet appointment of Oppenheimer's former colleague Lewis Strauss into a captivating procedural.

Ridley Scott’s Napoleon is a joyous paint-by-numbers biopic hitting every point between the French general’s first call to power through his downfall. Within this almost cradle-to-grave Campbellian journey, Napoleon is given scope to be strange and unheroic. He falls down the stairs in an ungainly escape. He paws the ground like a horse when he wants sex. His outbursts about boats and lamb chops are comically petulant. Scott’s preference for the cool over the accurate is well documented, and with Napoleon he aims for a great time rather than an important one. The framework is irrelevant.

Adam Driver as Enzo Ferrari in Ferrari. Photo: Sky Cinema/ NEON

This season’s best biopic is Michael Mann’s Ferrari. Opening flashback aside, Mann is uninterested in a rote path through challenges. The film hones in on preparations for the 1957 Mille Miglia. Enzo Ferrari pushes to create the world-leading racing car company and driving team, estranged wife Laura grapples with her place as company co-owner, and both mourn a son. The tensest threat is the cashing of a check. Test drives, engine sketches, coffee in front of the television, and opera trips are all permeated by their constant life-and-death preoccupations. The film’s unshowy presentation of an industry run by people with no sense of self-preservation, and its refusal to explain these urges, makes a deep impression.

Formulaic films are not failures by default. But after decades of biopics forgotten save for that Best Actor or Actress win, it is time to welcome new ways to portray a life through human, not mythic, journeys.

Oppenheimer and Napoleon are available to rent digitally; Ferrari is currently in cinemas