IFFR 2021: Small-scale film gems from Rotterdam

Part one of International Film Festival Rotterdam's two-part 2021 festival was sprinkled with enough small-scale gems to suggest arthouse and experimental cinema might still be in reasonable shape. We report back on some highlights

The gentle pop of 90s faves The Beautiful South was rattling around my head last weekend as I attended my first International Film Festival Rotterdam. Whether you were in Liverpool, Rome or anywhere, really, you could access this year’s edition from the comfort of your own sofa as the 50th IFFR became the latest film celebration to go virtual.

This necessary compromise that film festivals have had to make is certainly convenient (I was able to watch world premieres between laundry loads and hoovering), but the ease of access doesn't quite balance what's lost when these type of events move online. As well as a diminished viewing experience, swapping big screens for the laptop screen, its attendees missed the additional seasonings – the rare celluloid retrospectives, audio-visual installations and lively IRL chats with their fellow film-nuts – that give IFFR the distinct flavour that marks it out as a cinephile’s favourite among the major festivals.

Mustn’t grumble, though. While there were a few films in the programme that were hardly worth the trip from my bed to my laptop, nevermind a trip to the Netherlands, IFFR was sprinkled with enough small-scale gems to suggest arthouse cinema in 2021 might be in reasonable shape, even if arthouse cinemas aren’t.

The most exciting films I saw were small in scale but big on ideas and formal invention. Take Friends and Strangers, the debut from Australian filmmaker James Vaughan. It follows Ray (played by deadpan beanpole Fergus Wilson), a low-energy 20-something who makes a living as a wedding videographer. He’s not the most decisive type. He gets tied up in knots when asked about his video work's earning potential. “Remunerative” or “piddling”, he doesn't seem sure. He also seems to gets attached too easily; at one point he laments the loss of his favourite plastic water bottle. “Nice but earnest” is how one character aptly describes him.

The film opens with the most toe-curling camping holiday since Mike Leigh’s Nuts in May, when on a whim Ray goes on a road trip with a girl (Emma Diaz) who he barely knows. When the action moves to more urban spaces later in the movie, our hero is similarly ill at ease. He’s continually getting into situations where he’s compared with or intimidated by more earthy men; the kind of ruddy-cheeked, lager-chugging, cheerily malevolent blokes common in Aussie cinema.

Vaughan’s dialogue has the throwaway, seemingly inconsequential casualness of those American films from the mid-00s that were lumbered with the 'mumblecore' moniker. Visually, though, Friends and Strangers is Antonioni-like in its rigour and eye for architectural detail. The compositions, which shimmer in cool pastel shades, are often startling and off-kilter, with the fixed camera prone to missing some of the action as characters walk in and out of frame. Tone is similarly at odds. The droll humour and easy-going naturalism of the first half slowly transform into a nervy screwball with more than a hint of the surreal. The film world is not short of tales of post-millennial malaise and male insecurity, but this one is as fresh and crisp as a schooner of Tooheys.

Friends and Strangers runtime is a trim 84 minutes, but it looks bloated compared to The Dog Who Wouldn't Be Quiet and Pebbles, which are 73 and 74 minutes long respectively. The former, from Argentine filmmaker Ana Katz, follows another mild-mannered guy in crisis: soulful graphic designer Sebastian, played by the director’s brother Daniel Katz. Shot in soft monochrome, this gently comic slant on the mid-life-crisis movie takes the form of a handful of turbulent years in Sebastian’s life. His problems range from the quotidian (complaining neighbours; an uncaring boss) to the cosmic (a meteor hits the earth, changing the atmosphere of the whole planet), with our protagonist remaining doggedly stoic whatever the magnitude of the obstacle.

Temporal shifts aren’t signalled in the usual fashion of dissolves, slow fades or onscreen text. The primary indication of time passing is Sebastian’s appearance. In one scene he’ll be heavily bearded, shaggy-haired and so down on his luck he chows down on a stranger’s discarded, half-eaten sandwich, then a single edit later he’s clean-shaven and gainfully employed as an in-home carer. If Sebastian looks significantly older by the end of the film it’s because the actor is too: Katz shot her film piecemeal over six years. The filmmaking is simple but always surprising, particularly in two of the film’s most dramatic moments that happen outside of Sebastian's eye-line and are depicted in sketchy, hand-drawn animation. It's a modest, quietly moving epic.

Our hangdog heroes in Vaughan’s and Katz’s films are a world away in temperament from the misanthropic, misogynistic, often apoplectic father at the heart of PS Vinothraj’s fat-free Indian road movie Pebbles. Stomping around town like a man possessed, he drags his slight, sweet-natured son out of school and into the blazing sun to track down his wife, who’s fled to a neighbouring village. (The reason for her leaving doesn't need explaining.)

Between the father’s verbal tirades, Pebbles’ lucid action plays out with little dialogue and its images pop like a graphic novel, with wide shots often framing the two opposing figures against their heat-scorched landscape. Standing waiting for the bus, they could be a classic movie odd couple – the middle-aged cynic paired with the cute half-pint kid – but this is no buddy movie. The deadbeat dad is beyond rehabilitation, and all his son can hope to do is rebel against his patriarch along the way. All told, it's a nifty little fable. The IFFR judges agreed, awarding it the festival’s top award, the Golden Tiger.

Queena Li’s Bipolar, shot in dreamy black and white, takes us on a more meandering odyssey. While laying low at a posh retreat in Tibet, an unnamed Chinese singer (played by real-life singer Leah Dou) takes off with the brightly coloured lobster that’s the hotel's top attraction, after she’s compelled to liberate the creature and take it to its original home in the seas by Ming Island (think of them as Thermidor & Louise).

As much as a road trip, though, this is a journey into the singer’s subconscious. Some mysterious trauma in her past keeps threatening to bubble up during aquatic dream sequences featuring a pensive man dressed in black (Dou’s character dresses all in white). The title suggests this mystery figure represents the darker, depressive side of her psyche, although he could be a past lover or acquaintance for all the film elucidates. This deep dive into the character’s mental illness is somewhat at odds with the gorgeous but self-consciously wacky aesthetic, not to mention the inclusion of Dalí and Koons’ favourite mascot as her driving companion. The Fellini-esque visual overload and dream logic editing create thrilling scenes moment-to-moment but taken all together, Bipolar is a bit of a slog.

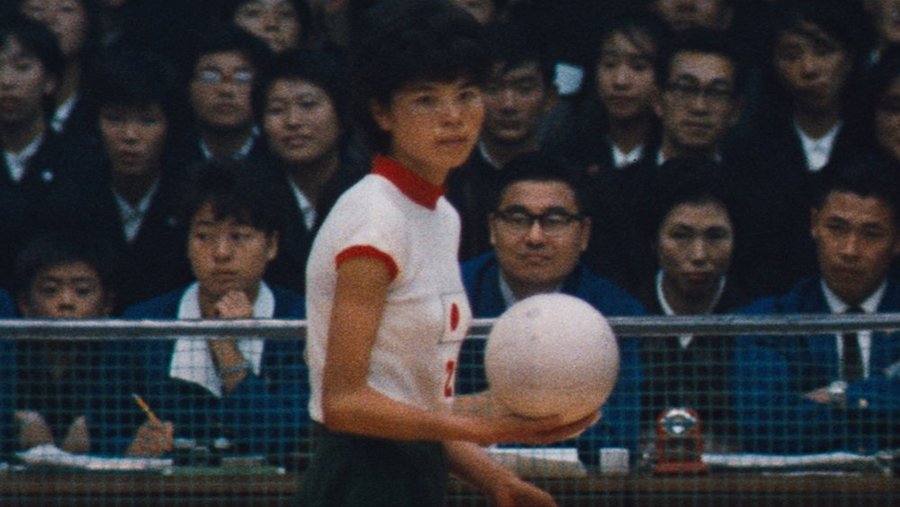

More satisfying was the beautifully crafted and gently experimental sports documentary The Witches of the Orient, which tells how a lowly Osaka textile factory’s volleyball team became an unstoppable force in the early 60s. Dubbed the "Oriental Witches" by western press, the team went on to represent Japan on a run of 258 undefeated games, winning the world championships and taking gold at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

There’s a reason most sports movies tend to favour underdogs rather than teams on juggernaut winning streaks, but French director Julien Faraut’s fleet-footed film overcomes any lack of tension in the narrative thanks to witty reconstructions of key matches and brutal training sessions using a rich cache of archive material, including the inventive inclusion of a kids’ anime the 'Witches' inspired called Attack No.1.

What really makes the film sing, though, is its genuine affection for these humble, hard-working, slightly stuffy sportswomen, with Faraut’s dynamic montage sequences insisting parallels between the team's gruelling training regimes and the industry of post-WWII Japan. Faraut reunites some of the 'Witches', still spry in their 70s, in the present day, introducing them on screen with trading-card like graphics of their specialist skills and their bonkers nicknames. Even those allergic to sports films will find themselves caught up in the story of Horseface, The Kettle, Blowfish et al.

IFFR 2021 ran 1-7 Feb, with the second half of the festival planned 2-6 Jun

Images: Friends and Strangers, The Dog Who Wouldn't Be Quiet, Bipolar, The Witches of the Orient; stills courtesy of IFFR