Bohemian Rhapsody, The Favourite and LGBTQ+ portrayals

Two films with queer protagonists – Bohemian Rhapsody and The Favourite – are in the running for Best Picture at the Oscars and Bafta awards. Only one, however, treats their character's sexuality with both the casualness and respect they deserve

In recent years, films with LGBTQ+ characters have carved out a prominent place for themselves in mainstream cinema. Awards and accolades are never far behind the critical and commercial success that these works have enjoyed, and this year is no different.

Inheriting the mantle from films like Carol, Moonlight and Call Me by Your Name, Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Favourite and Bryan Singer’s Bohemian Rhapsody look set to pick up awards at both the Baftas and the Oscars after a string of early victories at the Golden Globes. But while both are biopics of queer figures, the way these two films handle sexuality as a theme is strikingly different – and Bohemian Rhapsody does not fare well from the comparison.

“I want you to fuck me,” Queen Anne (Olivia Colman) tells her lover and confidante, Lady Sarah (Rachel Weisz), one night in The Favourite. The whole film ripples with this matter-of-factness, and while the women's affair is kept secret from the rest of the court, it is portrayed in a refreshingly straightforward manner for the audience. It is this bluntness that allows Lanthimos to do interesting things with the theme of sex and sexuality; a prickly love triangle plays out as the upstart Abigail, played by Emma Stone, begins to interfere with the balance of power between Weisz’s Lady Sarah and Colman’s ailing Queen Anne.

For all three characters, their sexuality is a weapon to be wielded skilfully and brutally, turning something historically associated with the suppression of women into a force for their political dominance. All the deliciously twisted machinations that play out between the queen and her favourites are rooted in the film’s refusal to shy away from its queer themes.

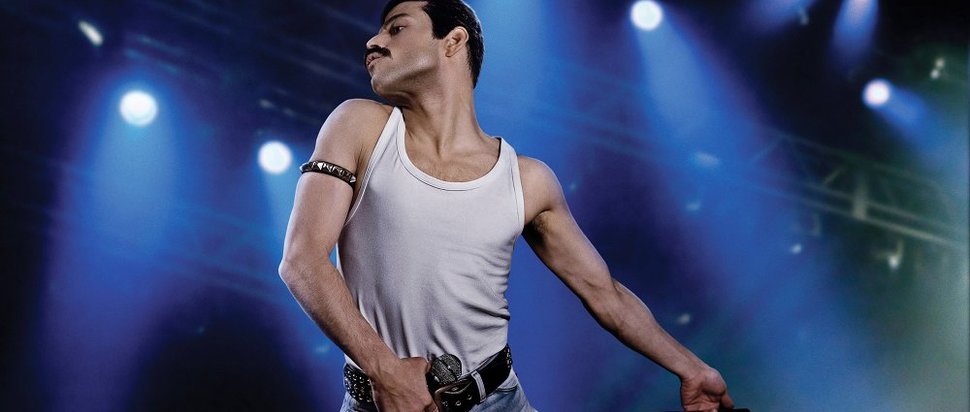

Bohemian Rhapsody, by this standard, is nothing short of a betrayal of its LGBTQ+ credentials and of the queer icon at the centre of the film. There is nothing matter-of-fact about its handling of Freddie Mercury’s complicated sexuality, which is almost always filtered through innuendo. In one scene, while Mercury (played by Rami Malek) is on tour in Middle America, he makes a call back to his girlfriend, Mary Austin, at a service station. While on the phone his eyes fall on a beefy American trucker as he wanders furtively into a public bathroom. Later, when Queen’s manager wakes Mercury in his hotel room after the band's epic Rock in Rio concert, a young male fan asleep on a sofa in Mercury's suite scrambles to get dressed and scarpers out the door.

When not watered down by cheap suggestion, the homosexual theme is played for laughs instead. When Queen's drummer, Roger Taylor (played in the film by Ben Hardy), has a creative tantrum during a recording session, Mercury quips, “there’s only room in this band for one hysterical queen”.

It is abundantly clear that Bohemian Rhapsody’s creators would much prefer to focus solely on Queen’s music – a fact that is evident even in the structure of the film itself. Instead of charting the meteoric rise and tragic fall of a complex musical prodigy, the plot is crafted to end on the climax of Queen’s most iconic performance – the 1985 Live Aid concert. The filmmakers do not seem particularly interested in Mercury’s seven-year long relationship with Jim Hutton (played by Aaron McCusker), who, in the film's version of the story, begins dating the singer on the morning of the Live Aid concert. Nor do the filmmakers seem particularly interested in the fact that Mercury lived for another six years after Live Aid, dying of Aids-related pneumonia in 1991 – why bother with the downbeat third act when you can cover all that with a few sentences before the end credits?

Perhaps the greatest betrayal of its supposed LGBT+ theme is this handling of Mercury’s HIV and Aids. One tweet summed up just how superficial the film’s engagement is with the disease that killed him: “Bohemian Rhapsody taught me that you can contract HIV via a passing glance at a handsome extra.” Mercury’s suffering is demoted to little more than a plot device to increase the tension in the final act: the damage done to his vocal cords by the disease threatens to scupper the band’s triumphant reunion on stage at Wembley.

As a big blockbuster film – already the highest grossing musical biopic in history – it is easy to see why Bohemian Rhapsody only skirts around the edges of Mercury’s sexuality. But it is also easy to see how big an opportunity was missed. The film will always seem like a shameless cash-grab because of its refusal to be straightforward about sexuality.

This, of course, is not the same as being explicitly sexual; it simply means being honest about the relationships and desires of characters, and not relegating them to euphemism or shockingly ill-judged plot devices. Audiences deserved more than an adequately-put-together medley of Queen’s greatest hits, as did the legacy of Freddie Mercury himself. Ultimately, it is because of this failure to engage maturely with LGBTQ+ sexuality, that although there will be two queens vying for dominance at the Baftas and Oscars in 2019, only one of them deserves the crown.

The Favourite and Bohemian Rhapsody are in cinemas now; the Bafta Awards take place in London on 10 Feb; the Oscars take place in Los Angeles on 25 Feb