Subversive Shorts: How Eastern Bloc animators evaded Soviet censors

This year's Samizdat Eastern European Film Festival opens with a programme of animation made during the tail end of Soviet rule. Czech filmmaker Michaela Pavlátová tells us how artistic freedom and creativity for animation flourished during this era

Eleven boundary-pushing animations open this year’s Samizdat Film Festival, Scotland’s first festival of Eastern European film which also celebrates the cinema of Central Europe, Central Asia and the Caucasus. Last year, nine surrealist animations were featured midway through the festival. This year, animation is promoted to the opening event, with Animations of the Late Eastern Bloc (1980-1997). It's a programme that reflects the art form’s previous ubiquity across Eastern and Central Europe at the beginning of almost all film outings, as Oscar-nominated Czech animator Michaela Pavlátová – whose 1991 short Řeči, Řeči, Řeči… (Words, Words, Words) features in the screening – explains.

Under Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, all feature films shown at the cinema were preceded by a state-funded short film that was either a documentary or animation. “Animation was part of [all] our lives,” says Pavlátová. And while the government’s hand meddled strongly with the documentaries and [live action] features, “somehow, they didn’t expect anything dangerous from animation,” which led to much weaker censorship. As a result, the animated films from this era survive as artefacts of untouched creative freedom in a way that live-action studio films from the same period do not.

“We didn't have so many choices [as we do now],” she says. “But somehow people were more into culture, because if there was a book out, all people read it.” People lived their lives locked in privacy, especially when a piece of Western media made it through the Iron Curtain. They held secret screenings and book groups. In this hybrid culture of ravenous artistic appetite and the stifling uniformity of the regime – of grey streets, grey clothes and empty shops, as Pavlátová recalls – animation was a “small, positive island of freedom.”

For most of us raised with that pervading image of the Eastern Bloc as a pallid and desolate landscape, the news that it was a place where animation was thriving may be hard to square. Compare that with the general health of animation in 2024: the industry is in disarray. Those working in Hollywood VFX describe a race to the bottom, where studios bid to work for minimal time and pay. Artists are leaving the profession in droves, putting their sleep and their mental health ahead of the visions of executives which are frankly uninspiring anyway. Closer to home in Prague, students at FAMU, the world’s fifth-oldest film school where Pavlátová is Chair of the Animation Department, are graduating into an almost non-existent market for their projects.

The Eastern Bloc was of course a less than ideal place to come of age. Even as the Communist party’s hold over everyday civilian life began to loosen under Perestroika, Gorbachev’s ill-fated reformation movement, higher education was far from a meritocracy. Raised by parents who weren’t members of the party, Pavlátová was only allowed into art school because her uncle was an artist and knew people in the commission. It was also a confusing place from which to set off on newly-permitted trips to Germany and France as a graduate. She recalls sitting on trains and being petrified by the threat of a stranger injecting drugs into her arm, so strong was the state propaganda back home.

Yet Pavlátová’s films were not overtly political and so she was practically never out of work. She doesn’t remember any deadlines – nor any studio notes – when she started making professional shorts in 1987. So long as she could keep producing films to screen before the main feature (the slot reserved in the West for adverts and trailers), she was left pretty much alone, save for the studio’s in-house script doctors, editors and animators who were ready to work at her disposal should she need them. After the Revolution in 1989, everything changed. The studio continued on its last legs for five years before new owners took over and stripped it for parts. “They were not interested in producing non-profit films,” she says.

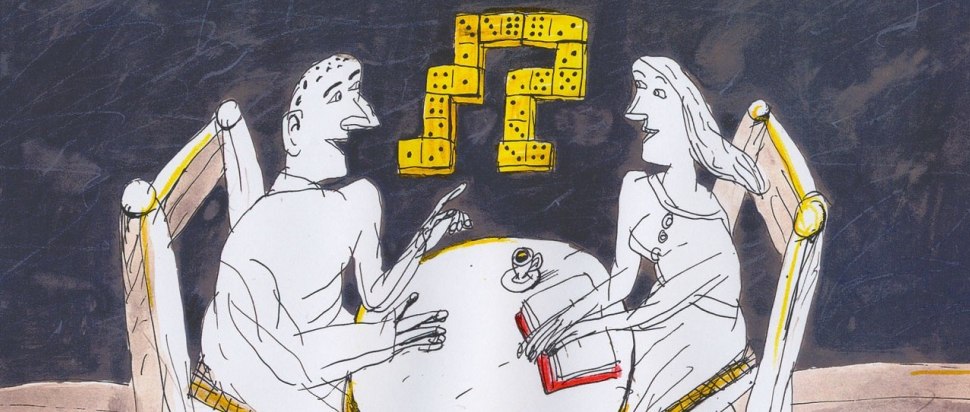

It was during this twilight period for the studio that Pavlátová’s Words, Words, Words was released. It survives as the product of a bygone age. Its experimental choice to portray the dialogues of coffee shop patrons solely visually – as all different shapes and symbols: lightning bolts; question marks; dominoes and puzzle pieces – is unlike anything being produced in the mainstream animation landscape today, reserved as it is for the latest crowdpleaser from Disney, Dreamworks or Illumination.

But given the wealth of independent creators sharing their work online nowadays, Pavlátová appears hopeful for the future. Her experiences have taught her that “mainstream also produces people who don’t want to make mainstream; that mainstream actually produces very big fans of art films.” Through sheer force of will, beautiful and groundbreaking works are still being made in makeshift spaces. And festivals such as Samizdat are helping them connect with their audiences. “They are small groups of people, but those people are hungry to see something different,” she says, smiling.

Samizdat Eastern European Film Festival runs at CCA and Glasgow Film Theatre, 1-5 Oct, and Summerhall, Edinburgh, 19 Oct

Animations of the Late Eastern Bloc (1980 - 1997), GFT, 1 Oct; Summerhall, 19 Oct

Full programme at samizdatfest.co.uk