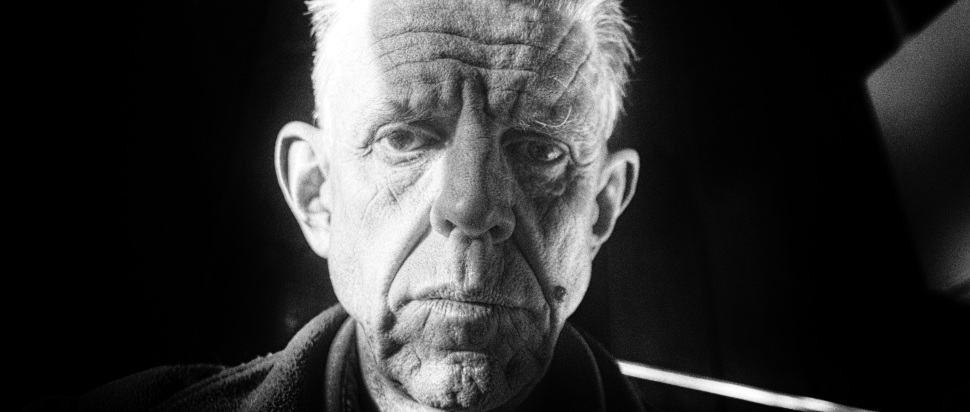

Remembering cult TV series Moviedrome with Alex Cox

Long before Netflix and torrent files, there was Moviedrome, the TV series from the 80s and 90s that introduced a generation of cinephiles to weird and wonderful cult films. We get nostalgic for this simpler time with Moviedrome's presenter, Alex Cox

It’s the early 90s, and a young film nut sits cross-legged in his pyjamas late on a Sunday night waiting for Mad Max 2 to start on TV. He’d recently seen and loved Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, the third part of George Miller’s postapocalyptic adventure series, and he’d read in this week’s TV guide that this earlier entry is even better. This was the way of the world for a young cinephile pre-internet. Nowadays, you can easily work your way through Letterboxd’s top 250 movies without leaving your laptop screen, but back then, it was more of a treasure hunt. Rather than binge, pre-internet cinephiles nibbled at crumbs they discovered on late-night Channel 4 or BBC Two. The aforementioned Mad Max 2 was one such morsel, but there was something special about this TV broadcast: it was preceded by an introduction from a curious man named Alex Cox, whom the boy would later learn was a great filmmaker in his own right. Readers, that young film nut was me, and like many other impressionable minds who grew up loving film in the 80s and 90s, I was about to get my mind blown. Forget Thunderdome; I was about to be welcomed into Moviedrome.

For those of you who didn’t grow up in this bygone era, Moviedrome was an idiosyncratic film season that ran on Sunday nights during the summers of 1988 to 1994 and then again from 1997 to 2000. Cox presented the first seven seasons while Mark Cousins presented the last five. All kinds of work screened – sci-fis, horrors, westerns, melodramas, gangster flicks – but the connective tissue was that the films were all offbeat in some way; they were lower-budget, edgy, political, daring and usually had some elements of excess (violence, sex or both).

Moviedrome has been off the airwaves for over a quarter of a century now, and the concept must sound positively prehistoric to younger audiences reared on streaming and video on demand, but it left a lasting impression on several generations of cinephiles. Ask any film fan from the UK of a certain age about Moviedrome and they’re sure to have fond memories of the weird and wonderful films it introduced them to. The lingering fondness for the series is so much so that BFI Southbank is marking 25 years since it left our screens with a two-month retrospective this summer of some of the most notable Moviedrome films. But the question is, why has Moviedrome left such a lasting impression?

An American Werewolf in London.

The show was the brainchild of Nick Freand Jones, who was part of the BBC’s programming acquisition team at the time. Over video from his home in London, Jones explains that Moviedrome had lowly origins. “When you bought films in those days, say from Warner Brothers or Universal or whoever, you’d buy a handful of big titles, classics and whatever the new crop of premieres were, and with them, they would expect you to take library titles to make up the bulk of the deal. So the BBC ended up with this phone-book-sized catalogue of movies from all over the place, from the 1930s to the present day. Lots of those films were playing the afternoon slots or in primetime, but there were always the odd curiosities that nobody knew quite what to do with. And often they were the most interesting films, to be honest.” Moviedrome became the ingenious vehicle with which to unleash the most obscure and gonzo of this vast film archive onto the public.

Cox wasn’t an obvious choice as host, but his distinctive presentation style had caught Jones' eye on Film Club, an earlier film series where noted British directors were invited each week to introduce a double bill. Many of these luminaries, like Lindsay Anderson, John Boorman and Terence Davies, took a professorial approach, but Cox was different. “He had kind of pungent opinions,” recalls Jones. “He's very bright, obviously. He knew technical stuff, but he also had cultural references. And he didn't look like anyone else you saw on telly in those days. So we thought, ‘Wow, this guy's really good. He's a natural television presenter but also, you know, a slightly odd type.’”

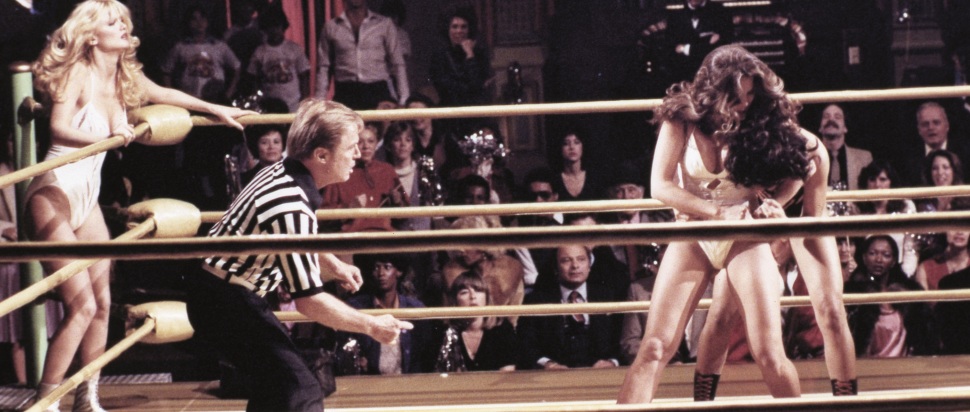

California Dolls. Credit: BFI National Archive.

The reason the director of Repo Man (1984) and Sid and Nancy (1986) agreed to slum it on late-night BBC Two was quite straightforward. “Oh, I had no money,” Cox tells me over video from his home in Southern Oregon. “I just made a film called Walker, and the studio hated it. They blacklisted me – I'd never work for an American studio, or any biggish British company, again. So I needed money, and Nick Jones very kindly asked me to present.” Jones picked the films and directed the wraparounds, while Cox wrote the intros and delivered them in his inimitable style. And one of the most bracing aspects of this style was he refused to paint a turd. If Cox didn’t like the film that had been programmed, he had no hesitation in showing his disdain. “The deal was that [Cox] could be as honest and forthright as he wanted,” says Jones. “We weren't asking him to sell these films. We just asked him to contextualise them.”

Cox reckons this lack of bullshit, the fact that he wasn’t trying to be a cheerleader for the film you were about to watch, was one of the reasons why Moviedrome worked so well. “These were marginal films, so it was possible to approach describing them in a different way," explains Cox. "It wasn't necessary to pretend that everything was absolutely great, you know? Whereas, if the BBC had spent a ton of money on a Harry Potter film, say, you couldn't have the guy beforehand saying, ‘Well, you know, a lot of this is really shit.’ But with Moviedrome we could, not that I would have said anything so crude.”

Politics was also central to Cox’s intros. “Well filmmaking is a very political process because it involves getting hold of a lot of money, and that's very political,” Cox says. “It involves going to a bank or a big corporation or wealthy individuals and trying to get them to spend money, and they're only going to do that if they feel that the project fits their agenda. So it's always fascinating to see how interesting films get made, in spite of that. In spite of the difficulty of wrestling money from the claws of its owners and putting it to good use.”

Les Diaboliques. Credit: BFI National Archive.

Does Cox think his punky style and vaguely Marxist attitudes would fly at the BBC in 2025? “Oh, I'd be in jail now. They bang me up with Assange and Asa Winstanley. I mean, you can't express political opinions now, in this current climate. We're in a very repressive, quasi-fascist environment now, and it's very troubling.” To paraphrase Marx: TV is the opium of the masses. “That’s the thing about TV,” continues Cox, “it's supposed to be entertaining. It's not supposed to be political or have any kind of context to it, but context is everything, and especially in films, because, as I say, making them is political.”

To anyone reading about Moviedrome who was born this century, this all might sound rather quaint. Not just having the idea of a mainstream media in which one could freely speak one's mind, but the whole concept of tuning in to a TV show on a specific day at an allotted time to be introduced by a presenter to a film you’ve heard little about. Who would need such a contrivance in 2025 when there’s Netflix? But if I’m nostalgic for any aspect of Moviedrome, it’s the joy of not making the decision of what to watch; of not being fed by an algorithm or having to wade through a plethora of options available across multiple streaming platforms. I miss those days of less abundance when your movie choices were dictated by simply what’s on telly and the absolute elation you'd feel when you'd stumble across a masterpiece by pure happenstance.

“In theory, everything's out there on the internet, pretty much,” says Cox. “If you just spend long enough looking for, say, The Mattei Affair, eventually you'll find a bootleg copy that somebody's uploaded. Maybe it will even have subtitles! But you have to know what you're looking for, you know?” He compares Moviedrome to another anachronism: the video rental shop. “You might go in looking for Get Out, but it’s out on loan, and the guy behind the counter recommends Dawn of the Dead and you go home with that instead,” says Cox. “Maybe that’s what Moviedrome was doing: you could say that it was like a bunch of films on the shelf of a video shop, and I was the guy behind the cash register.”

The Wicker Man.

Nostalgia can be a dangerous thing, though. Moviedrome is very dear to my heart. Over its 12 seasons, it presented some wonderful films. It gave me my first taste of cult directors like Donald Cammell, John Carpenter and Walter Hill, and introduced me to B-movie specialists like Larry Cohen, Edgar G Ulmer and Robert Aldrich. It helped fuel a passion for film in me and so many other people, but it wasn’t perfect. It certainly tended towards the macho end of the movie spectrum. While reminding myself of the films shown on Moviedrome, I was mortified to notice that of the 207 titles that screened, only one was directed by a woman – Ida Lapido’s fat-free noir The Hitch-Hiker, which appeared in the 12th and final season. It’s a pretty shameful statistic, and it can’t simply be put down to the dearth of women who got to make films in the first century of filmmaking. The team wouldn’t have had to look too hard to find work directed by women that fit the Moviedrome ethos: Penelope Spheeris’s punky drama Suburbia, Kathryn Bigelow's soulful vampire movie Near Dark or Lizzie Borden's sci-fi tinged feminist provocation Born In Flames spring to mind, as do Bette Gordon’s voyeuristic Variety, Liliana Cavani’s shocking The Night Porter and Mary Lambert’s gothic Pet Sematary. The films of the New Queer Cinema are conspicuous by their absence too (no Todd Haynes, no Gregg Araki, no Derek Jarman).

It would be wrong, then, to look at Moviedrome through rose-tinted glasses. But if it were to make a glorious return, these blind spots would surely be corrected, especially with a less macho host. When I ask Jones what young British filmmaker he might cast today if a 13th Moviedrome season were commissioned, he replies by email a few days later with a tantalising list that includes Prano Bailey Bond, Molly Manning Walker and Alice Lowe. But I’m not sure Cox’s punky energy could quite be recreated in the same way. I guess Thomas Wolfe was right, you can’t go home again, unless, that is, you’re in the vicinity of the BFI Southbank this summer, where Cox will be introducing films like The Great Silence, Sweet Smell of Success and The Wicker Man, the film that kicked off the first series.

Moviedrome: Bringing the Cult TV Series to the Big Screen is at BFI Southbank from 1 Jul-31 Aug; a collection of Moviedrome films, including a new short documentary about the series, will also be available to stream on BFI Player

bfi.org.uk/whatson