Naqqash Khalid on In Camera

The relentless grind of being a jobbing actor of colour in the prejudiced UK film industry becomes the stuff of nightmares in Naqqash Khalid's debut feature In Camera. Khalid talks to us about his bold, thrillingly experimental approach

“We don’t live in a three-act-structure time,” suggests Naqqash Khalid when trying to convey how he came to make his bold and experimental debut feature, In Camera. “There’s something about the three-act structure that just doesn’t reflect our life today,” he continues. “I knew that I wanted to make something that was structurally reflective of now.” The film is reflective of now in more than just its structure. Part biting satire of the British film industry, part meditation on notions of performance and identity, it's a film rooted firmly in contemporary society both in its form and its content.

In Camera was several years in gestation, and developed over time with support from the BBC, BFI and Creative UK. Its exact inception is difficult for Naqaash to recall precisely (“I’m trying to remember!”) but he recollects the impulse clearly: “I knew I wanted to write this film; I wanted to write a fairy tale, and I wanted it to be about an actor. I'm not entirely sure why, but looking back now, it feels like I had all of these things to say about culture and identity and an actor felt like the perfect vehicle to say all of these things.”

The actor in question is Aden, played by the utterly captivating Nabhaan Rizwan. In Camera follows him as he searches for a role to play and features several scenes in which he confronts the realities of being a young British Asian actor. “I think there is a lot of expectation and projection on to actors – and directors – in this medium,” says Khalid. “Because it's a capitalist medium. People have ideas of who you could be in a marketplace and the kinds of films you could make – and you have to learn how to navigate that. I think everyone has expectations of people.”

While Aden is constantly pigeonholed by other people, his own persona is continually shifting and morphing, like water searching for a vessel to give it shape. The film’s unconventional structure referred to above emphasises this with cadenced and cyclical non-linear editing. “I had this really set structure in my head of how I wanted to make it so that it felt like an album, where every scene was a track,” explains Khalid, “I think you have to invent the structure and the tools to make every film that you work on. This film was just asking for this kind of looping structure, almost like geometrical abstraction. I just wanted it to tap into something that represented more life as it feels, not as it is.”

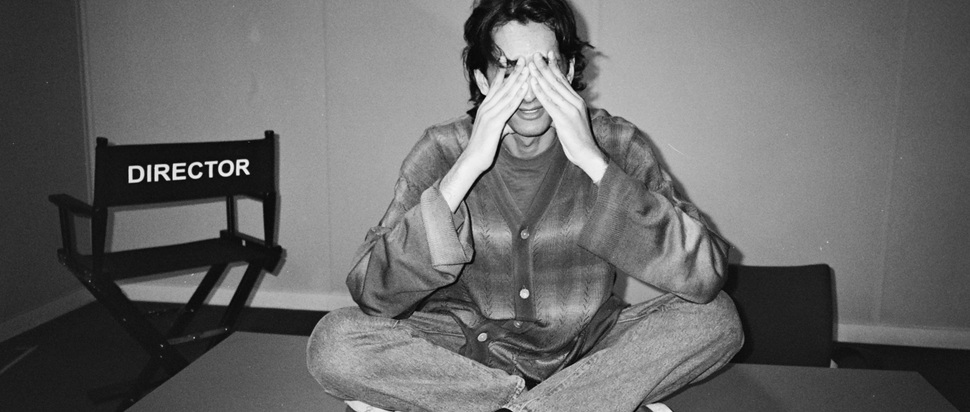

Naqqash Khalid. Image credit: Juliette Larthe

This loose narrative chronology allowed Khalid to genuinely play with the edit over the film’s gestation period, free to move scenes and sequences completely. “There was a sense of fluidity,” he says, “being able to restructure the film in the edit. We’d be like, ‘What if we took this scene and just put it there?’ And we did that a lot.”

The structural invention is, as Khalid has stated, all about tying the film’s flow to the modern human condition. “I was reflecting a lot on, you know, when you're on Instagram,” he muses. “You're scrolling and you like a post about a genocide, then one about your friends getting engaged, then we're not paying doctors enough and everyone is striking, you know? We're looking at all this information – the good, the bad, the highs, the lows – simultaneously. That's our experience of the world and it's quite fragmented and fractured. I think, as artists, we have to respond to what is happening in the world. I think that a lot of that is structural innovation; film should reflect our time. The exciting thing about cinema is it's still a young medium and that invention and that contribution is to this shared language.”

It's not always the case that a young filmmaker hoping to release work in UK cinemas would feel this way. And if they did, they would rarely have the strength of will to stick to their guns. “I thought, ‘This might be the only opportunity I ever get to make a film and I'm only going to make the film I want to make,’” says Khalid. ”I'm not trying to make career decisions. I'm not thinking… ‘In five years I'd like to be here’ or ‘On my second film, I'd like to do this.’ I was very adamant that if this is the only film I'm going to make, then I'm going to make the film that I want to make. If I never make a film after this again, I'll be happy because I was able to do what I wanted to do. I just kept reminding myself of that when things were challenging.”

Things were, of course, challenging. This is a low-budget indie production after all. But Khalid found being pushed critically – by funders or by the iFeatures programme through which he developed the film – to be an incredibly rewarding and enriching experience, and very much to the film’s merit. “This is what I wanted to do,” Khalid says on the end result. “It has those feelings that I was trying to articulate within it. I'm really happy with it.”

In Camera is released 13 Sep by CONIC