Matthew Rankin on gonzo biopic The Twentieth Century

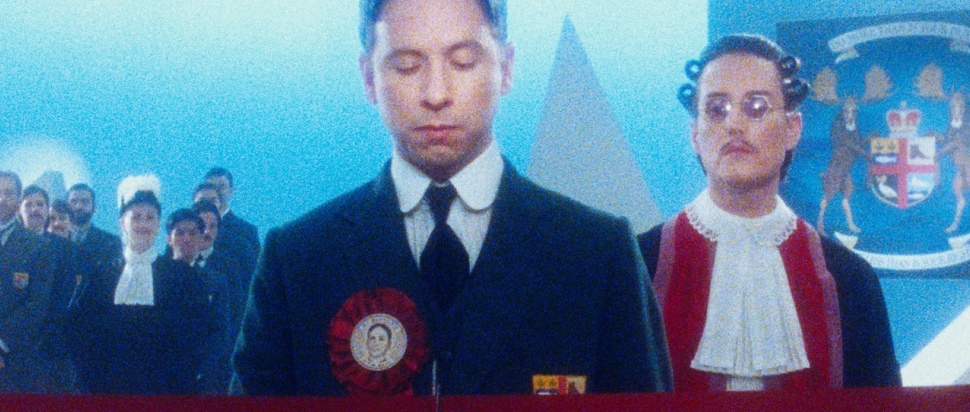

Matthew Rankin's wildly imaginative debut feature, The Twentieth Century, is a bizarro reimagining of Canada's most celebrated prime minister

Set in 1899, Matthew Rankin’s The Twentieth Century tells the story of the early political machinations of a young, uptight and ambitious William Lyon Mackenzie King, who would go on to become Canada’s longest-serving prime minister. He held the post for 21 years over three terms, which included leading the country through the Second World War. He’s on the $50 bill. He’s basically the Canadian Churchill.

This is no Darkest Hour or Young Winston, however, but you’ll quickly work that out for yourself. Maybe you'll be clued-in when, in lieu of a general election, King takes part in a contest of Canadian manhood to decide if he’s qualified to become PM – the challenges include log sniffing, butter churning and baby seal clubbing. Or maybe it’ll be the subplot about King’s erotic fixation with putrid footwear that tells you this isn't your standard-issue biopic. Or maybe it’s just the massive ejaculating cactus that manifests as a physical representation of King’s repressed horniness that gives it away.

The Twentieth Century may be a work of gonzo surrealism that grows more feverishly demented with every passing second of its 90-minute runtime, but this doesn’t mean Rankin’s film is completely devoid of historical elements. Speaking to the 40-year-old Winnipegian at last year’s Glasgow Film Festival, he tells us to think of The Twentieth Century as a new sub-genre: a “biographical nightmare”.

King was a keen diarist. Rankin has taken those journal entries and liberally read between the lines. “Everything in the film has some link to something that really happened to him, some relationship that was really happening, some sort of pressure in his life, but it's sort of transmogrified through this Freudian prism,” he explains. “So I did think of the film as a biopic but one which is sort of penetrating the subconscious record of the past.”

The warped nature of The Twentieth Century's narrative is mirrored in the wild artifice of its aesthetic. Shot on grainy 16mm with old-school colour tinting, it looks like it was filmed in King’s own lifetime. Expressionistic sets evoking Victorian workhouses, Art Deco palaces and Canada’s dramatic landscapes are conjured up from lo-fi matte painted backdrops, Lotte Reiniger-esque animations and crude MDF cutouts that look like they’d tumble over if a cast member were to fart.

On one level, Rankin’s stylised design was a way to make a virtue out of his threadbare budget. “I knew that if I tried to do some sort of glossy Spielbergian, traditional, conventional period piece, my budget would just evaporate within a couple of minutes. So I knew that if I just did the opposite of that, if I embraced artifice, made this world very fake, worked in more of a theatrical tradition, then my budget would go further.”

On a deeper level, however, the art department’s minimalist sets reflect King’s bankrupt morals and shallow politics. For Rankin, it also represents the artificiality of nationhood itself. “I wanted the viewer to have this encounter of Canada as an artificial space,” he explains. “It's a structure that has been grafted upon the natural landscape; it's a fantasy that has been invented. So essentially it's a film about the empty triumph of nation-building.”

Rankin is hardly the first filmmaker to play fast and loose with the truth when examining historical events. Even straight-laced biopics have to twist and distort real life to fit a narrative. Rankin studied history at university, so he knows more than most that the chronicling of facts, be it an academic treatise or a glossy Hollywood feature, involves some fudging and fictionalisation.

“I remember one of my professors at university,” recalls Rankin, “she devoted a whole lecture to ranting about the beauty of Leonardo DiCaprio's teeth in Titanic. She was like, ‘there's just no way that someone in 1912 who was poor would have such a beautiful smile. His teeth would be rotting and falling out of his head.’ Maybe James Cameron was aware of that, maybe he wasn't, but some kind of translation took place. He went, ‘Okay, well maybe my romance plot isn't gonna work because his teeth are rotting.’ So we cheat, there are embellishments.”

What would that pedantic lecturer make of The Twentieth Century?

“My sense is that she, and other historians, would be much more comfortable with a film like mine, which makes no pretence of being credible. No one is going to leave the film thinking, ‘Ah, well, that's what happened.’”

What will they be thinking? “People are going to be leaving more likely thinking, ‘Well, what part of that is true, and what part of it is false?’” smiles Rankin. “And that's actually a good tension for a viewer to have when they watch a historical film.”

We suspect Rankin probably knows that the actual first question people will ask themselves when they finish watching The Twentieth Century is, “WTF?” Questions of historical verisimilitude might come later.

The Twentieth Century is available on MUBI from 15 Feb