Luke Fowler on his Margaret Tait film Being in a Place

Glasgow-based artist, filmmaker and musician Luke Fowler discusses his new film Being in a Place – a complex portrait of fellow Scottish filmmaker Margaret Tait

“It was incredible,” says Luke Fowler of his journeys up to Orkney to capture the locale for his new film Being in a Place, a portrait of Scottish artist-filmmaker Margaret Tait and, crucially, the area that she called home and so often filmed herself. “It's a place that’s steeped in history,” Fowler says. “There are standing stones, early settlements, the Italian Chapel – which was where they kept prisoners of war during WWII. It's a place that cruise ships come into in the summer, there are waves of tourists coming into Orkney to see these sites.”

You won’t see these awe-inspiring landmarks and vistas in Tait’s work though. “Margaret was never interested in filming those things,” says Fowler. “She was very disdainful of documentaries made in Orkney, just documentaries in general. When you go to Orkney as someone following in Margaret's footsteps, you're trying to see the shape of a place in the way that she captured it.”

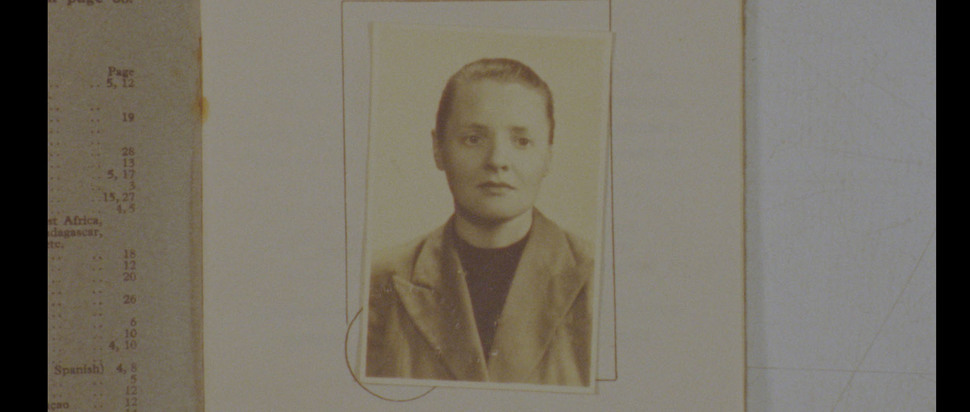

This is perhaps all the more essential for Fowler’s film, which combines the footage shot during his pilgrimages with marginalia from Tait’s own archive. “There were some parts of the archive that the National Library didn't want to take,” explains Fowler, “offcuts and rushes and alternative versions.” Writer and researcher Sarah Neely had, wisely, decided that these bits and pieces were too precious to throw away. These reels, which had only ever been seen by an archivist, seemed like a potential goldmine to Fowler. “This was a vital way of understanding Margaret – through the things that didn't end up in her films, that were left on the cutting room floor. You can start to understand her process. So, I proposed that we should make a film about this ‘unofficial’ archive.”

There were all sorts of treasures to be unearthed in the collection – from a sound version of These Walls (1974) which had previously only been known as a silent piece, to offcuts and outtakes from other well-known films like Land Makar (1981), Happy Bees (1954), and A Portrait of Ga (1952). “And another portrait that was never finished, of her father,” reveals Fowler, “called Daddy at Harray Loch.” After digitising them, these fragments became his material before a template by which to shape it appeared in the form of a short proposal Tait had submitted, unsuccessfully, for a Channel 4 film called Heart Landscape.

“The particular 'heart landscape' that she drew out on this map was the road from her house to her studio,” says Fowler. “It's a microcosm of Orkney; it contains heathland and moorland, vast swathes of untouched countryside, but then also has these like little towns like Dounby and places like farms and foundries where they're making the steel fences for cattle. It's quite a localised, specific landscape. The more that you get out of the car and actually look, and go there regularly, and see things in different seasons, the more you start to realise that your view of a place is based on specific time.”

In this observation, Fowler seems to be acknowledging that Tait’s sensibility, of looking away from the obvious into the quotidian minutiae, seems to chime quite well with Fowler’s own filmmaking approach. “I'm interested in this idea of Cubist cinema,” he explains, “which was something raised in the 70s – how to make an equivalent of Cubism within cinema. Using multiple exposures, or multiple perspectives, that are shown within a prism or diffracted – multiple fragments of place that are seen in sort of bursts, rather than in long shots.

“It's going against the idea of the picturesque,” he continues, “against this idea of a preferred perspective, a romantic landscape. This is much more like using the camera to show 360 degrees; to show slices of air, to show the contingent nature of the landscape, and how time and the body changes the way we view landscape. Everyone is seeing things differently. It's very personal, and it's conditioned by what you do: a farmer sees the landscape in a different way than a tourist would see that landscape.”

When asked whether he actively seeks to embrace the artistic vision of his subjects in portraits like this, Fowler professes more of an affinity to the fundamental nature of the experimental. “I think it's sort of like radical politics,” he suggests. “People seem to think that the avant-garde is something you grow out of as your films mature and that you have to aspire towards making feature-length, narrative films. I don't believe that; I think that’s a commercial disease driven by financial pressures, this idea that we have to aspire towards making a Netflix series or something like that, and that's a sign of success. For me, the experimental – experimental art like Duchamp, John Cage, Blinky Palermo or Margaret Tait – is something to live by. It's not something to gaze at in a museum, to have a fleeting view of, to grow out of; it's a rule to live by.”

Being in a Place has its UK premiere at Berwick Film Festival on Sun 5 Mar

luke-fowler.com

Filmography (selected): For Dan (2021), Patrick (2020), Cézanne (2019), Enceindre (2018), Mum’s Cards (2018), Depositions (2014), To the Editor of Amateur Photographer (2014, co-directed with Mark Fell), The Poor Stockinger, the Luddite Cropper and the deluded followers of Joanna Southcott (2012), All Divided Selves (2011), An Abbeyview Film (2008), Bogman Palmjaguar (2008), Pilgrimage From Scattered Points (2006), The Way Out (2003, co-directed with Kosten Koper), What You See Is Where You’re At (2001)