Invisible Women on reframing film history

The mission of archive activist film collective Invisible Women is to shine a light on women filmmakers who've fallen through the cracks of film history. We chat to them about their slew of upcoming film retrospectives and seasons

The ephemerality of film is increasingly apparent. Only a fraction of films made each year see a wide release. Preservation, exhibition, and archiving are fraught issues due to destroyed national libraries, corporate tax schemes, and major distributors refusing physical releases. Compounding these issues is a power imbalance in who makes, funds, distributes, and champions films, the result of which is that the works most often held up as the 'greats' are almost exclusively by white men. The magnitude of cinema history can make archival exploration daunting, but filling gaps and championing voices that – due to their gender, race, class, nationality, or other factors – are overlooked by the canon is vital.

One group doing this essential work is film collective Invisible Women. Since their first event in 2017, co-founders and curators Camilla Baier and Rachel Pronger – alongside curator Lauren Clarke – have been working with cinemas and festivals across the world to facilitate programmes that champion women and filmmakers with marginalised identities, bringing their under-recognised work to a wider audience and reframing the broader story of film. Their ten-point manifesto declares principles such as “to curate is a privilege”, “the archive is our past, present and future” and “blow away the dust – make it real, tangible, now!”.

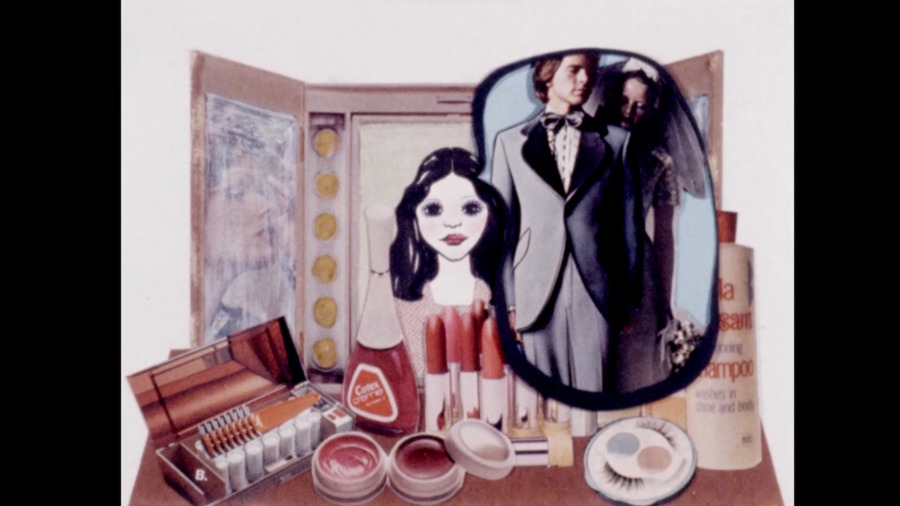

In Scotland, Invisible Women's schedule is packed. Having recently finished a retrospective on Colombian documentarian Marta Rodriguez at Edinburgh’s CinemaAttic in January, they further explore Latin American cinema with a brace of programmes at Glasgow Short Film Festival featuring shorts by Mexican feminist film collective Cine Mujer. Titled Cine Mujer: Shifting the Narrative, the two strands – The Personal is Political and It’s Not by Choice – boldly explore societal norms and pressures that still resonate despite Colectivo Cine Mujer’s roots in 1960s/1970s radical student politics.

And if you are a woman / ¿Y si eres mujer? (Dir. Guadalupe Sánchez Sosa)

At Glasgow Film Festival, meanwhile, the collective will take part in a panel following Morocco, part of GFF's What Will the Men Wear? strand, which explores the star power of three of Hollywood’s most subversive female stars of the 1930s: Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn. Invisible Women also present their own retrospective at the festival called Wild Flower, Flaming Star, celebrating the prolific Mexican actress Dolores del Río. And once GFF comes to a close, they’ll explore the great Hollywood director Dorothy Arzner at the Glasgow Film Theatre as part of the cinema’s regular Cinemasters project.

The Marta Rodriguez series and Cine Mujer: Shifting the Narrative both aim to introduce UK audiences to radical Latin American cinema. Baier, who has lived in Mexico, led the way on access. “We were doing a presentation about feminist film collectives and started looking at Mexico City collectives born from the student movement,” she explains. “Cine Mujer was the one where we could find the most films – so many that we had to screen them rather than just present them.” The programme at GSFF follows a 2021 programme at the London Short Film Festival. “I wrote to every single person I could find that had worked with Cine Mujer,” Baier says. “We found a festival in Chile restoring and digitising these films. And last year, a lot of restoration was done in Mexico,” she adds, noting a focus on historical revisionism in the Mexican art world. One film, digitised last year, will be a UK premiere.

The Rodriguez season featured four films, some of her earliest; Invisible Women hopes to show her later work in upcoming seasons. Rodriguez is still working in her 90s, and the team began to notice that many female filmmakers, including those of Cine Mujer, become permanently associated with their early works rather than their holistic, evolving careers. “[Critics] tend to contain them in a particular moment, like the second wave,” Pronger says, explaining how dismissive and reductive initial criticism can limit rediscovery, focusing attention on to filmmakers' breakouts. “I'm worried we fossilise older female filmmakers unless they’re really established, like Agnieszka Holland. Critical reevaluation is ongoing. Also, as we progress, we challenge our own assumptions around what we should screen and when.”

Clarke explains that interrogating the choice of certain retrospectives at certain times is key. “The Cine Mujer films in particular are so relevant to current conversations around women's autonomy, sex work, gender, and unions,” she says. “There’s a resonance and frustration when engaging with these pieces. We’re hoping to foster conversation about these concerns that are consistently imposed on women and people with marginalised identities.”

“So little Latin American cinema is released in the UK,” Pronger adds. “There’s an amazing new generation, particularly of Mexican female filmmakers like Lila Avilés [Tótem, The Chambermaid] making incredible work. We can access films that others in the UK can’t. The del Río season involved extensive negotiation with Mexican archives. It would have been impossible without Camilla, so it's almost become a mission.”

Dolores del Río in La Otra

Del Río had a star career in the US and Mexico, appearing in 69 films. Invisible Women’s GFF retrospective offers a tantalising taste of her range through four key features. “She bridges the Mexican and Hollywood golden ages,” says Pronger. “She was one of the first Latin American stars widely seen in the US. But because she was a trailblazer, there's a lot of compromise in terms of the way she was portrayed – often very stereotyped or cast across ethnicities. She's such an interesting, intelligent, and fascinating person who was maybe reduced into a box by the ways she was shown in Hollywood.”

Del Río was a huge star in her home nation, but it was in the US that she first came to prominence. “She started in pre-Hays Code silent films – some were raunchy as hell, like The Loves of Carmen from 1927,” says Baier. “She came from a really wealthy family that can be traced back to Spanish royalty and was called the ‘Princess of Mexico’. But her first talkies are almost humiliating. I can't imagine the same thing happening to an American star.” White Europeans with accents, like Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, were also exoticised but with greater reverence.

This horrendous treatment of del Río raises questions about a curator’s responsibility to mediate work: there is a balance between examining work within the problematic context of its time, and presenting portrayals that degrade actor and subject. “You see fetishisation so much across the Hollywood studio era,” says Clarke “but is showing some of these films useful? I think we've selected a spread that taps into such stereotyping, but not ones where you think, ‘What the hell was going on?’”

“The del Río Hollywood films we love are the ones where she transcends the part she was given,” says Pronger. “She is such a charismatic performer and incredibly dignified presence, and in Flying Down to Rio and Flaming Star [screening at GFF] she is magnetic and brilliant to watch. She's a trailblazer and a cautionary tale, and created a long and amazing career for herself within these circumstances. And typecasting Latin American talent in the US is still a huge problem.”

This work doubles as film preservation. The headquarters of the Chilean film festival that digitised Cine Mujer's films burned down early this year, and Invisible Women shared some files back. They also commission subtitles when the budget exists, allowing films to reach wider audiences and help create a network of distribution. “That can be limiting in terms of what we end up screening in the final programme,” says Clarke, “but keeping films moving builds a whole community ecosystem.”

Dance, Girl, Dance (Dir. Dorothy Arzner)

Cinemasters: Dorothy Arzner comes next. Clarke feels her directorial work, spanning from 1927 to 1943, exemplifies the evolution of characters pre- and post-Hays Code. “You see a difference – punishment if someone does wrong – but someone as smart and intelligent as Arzner sneaks in critiques and circumvents these ideas,” she says. “You’re always well aware of where her critiques are – how she’s bringing in queerness, how she pointedly questions different ideas around women’s role in society.”

“I don’t notice the impact [of the Code] as much on Arzner's films,” adds Proger, “because they are critiques of heterosexual marriage and of the interaction between patriarchy, capitalism, gender, and class” – the latter point being a relative rarity in American films of the time. “She gets forgotten and rediscovered and then forgotten again. But I don’t see how Arzner is any less interesting, subversive, or modern than Billy Wilder.”

After months of research and curation, the team is excited these films will be screened in cinemas. It will be a first for many in the audience, and a very overdue first for many of these films.

Cine Mujer: Shifting the Narrative, CCA, 21-22 Mar part of GSFF

What Will the Men Wear?: Morocco + Recorded Introduction and Panel Discussion, CCA, 29 Feb, 6pm, part of GFF

Wild Flower, Flaming Star: The Films of Dolores del Río, CCA & GFT, 29 Feb-7 Mar, part of GFF

Cinemasters: Dorothy Arzner, GFT, 12 Mar-3 Apr

invisible-women.co.uk

instagram.com/invisiblewomen_archives