Charlie Shackleton on Zodiac Killer Project

Charlie Shackleton was about to make a film about the Zodiac Killer when the rights to the source material fell through, leaving him to make Zodiac Killer Project, a meta documentary about the film he wasn't permitted to make

Charlie Shackleton has quietly become one of the most prolific and subversive non-fiction filmmakers in the UK, and his playful and often ingenious docs and visual essays are regular fixtures at international film festivals around the world. That’s not to say getting new projects off the ground is a walk in the park, as he discovered with his latest work.

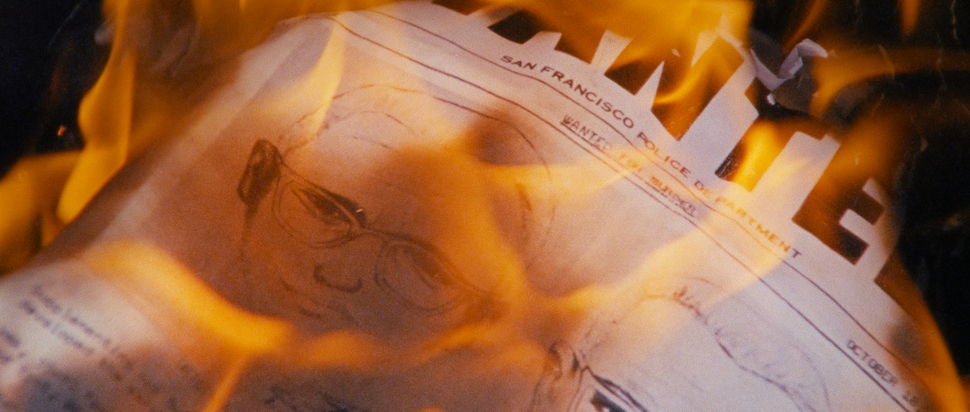

“Obviously it's not the first time I've had a project fall apart, even fairly far along,” explains Shackleton in reference to the unusual inception of his newest film, Zodiac Killer Project. The filmmaker’s original intention was to make a true crime documentary based upon Lyndon E. Lafferty’s 2012 book The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge. Lafferty was a former highway patrol officer who believed he’d had an encounter with the Zodiac Killer – the unidentified serial killer who terrorised the San Francisco Bay Area between December 1968 and October 1969. His book makes the case for his theory of who the killer was, and Shackleton was all set to adapt it until Lafferty’s estate had a change of heart and decided not to permit him the rights. “I thought I would just kind of lick my wounds for a few weeks or a month and then move on,” he recalls. “There might be some element of the project that could inspire a new idea. I hate waste, so anywhere I can take some development work and find a new use for it, I'm happy. But in this case, more than any other, I just felt dogged by it.”

Shackleton would find himself sitting with friends, insistently explaining his vision for this unrealised film, describing entire sequences and arcs and the intricate plans he had in his head for what a certain shot or transition would look like. “At a certain point, before I was even imagining it as a critique of the true crime genre or anything like that, I was just quite interested in this idea of a creative failure, a project that can never come to be, and what that is when it just exists as this unfulfilled idea.”

He thought about making a film that explored this notion of artistic frustration and one that was centred on a missing artefact, an impossible object. “What's more, I was interested in the idea that it could have this ambitious formal device of the film about the unmade film basically being structurally identical to it,” he explains. “It would be like real time, so you're getting the audience to imagine the thing they're palpably not seeing, minute by minute, beat by beat, revelation by revelation. That was very exciting to me, albeit not remotely as exciting as it would have been if they turned around and said, ‘actually, you can make the [originally planned] film.’”

What Shackleton has made in its place is a kind of stand-in. It features a selection of new 16mm footage shot around California, in the guise of imagery that might have been in the original film as part of recreations had the project gone ahead. Instead, in Zodiac Killer Project, they are largely empty, banal landscapes accompanied by arch inserts mimicking the genre tropes of the true crime doc and presented with Shackleton’s own improvised commentary as he describes the film he would have made, telling the basic tale of Lafferty’s book using alternative sources and sporadic readings from the original, inspirational text.

Photo by Xenia Patricia

For those who have seen Shackleton’s work before – whether that is his one-to-one VR performance piece As Mine Exactly, short films and video essays like Copycat and Histoire(s) du TikTok, the TV special Missing Episode, or features like Beyond Clueless and Fear Itself – the film he ended up making arguably feels more like a Charlie Shackleton film than the one he originally planned to make.

“Yeah, that's an interesting thought, actually,” says Shackleton when I put this to him. “The thing I've made is so much more unconventional than the thing I was planning to make, but, in some ways, it's also safer ground for me. I’m certainly deploying a lot more of the formal and artistic devices that I've deployed before, and never actually thought about it in those terms. For one thing, the true crime film I was planning to make, even if a big part of the appeal was the commercial prospect of something like that, I wouldn't have been keen to make it if I didn't think I could do something interesting with it.”

Shackleton explains that what we see in Zodiac Killer Project is a somewhat simplified version of the original. “I stress the elements that would have been most formulaic, because it's easier to conjure those for people, and they have more resonance when you're talking about the true crime genre at large. Honestly, though, it didn't even occur to me that this was a genre study until it started screening. As I say, the origin was much more of a formal experiment, and I was quite late to the idea that what I'd made in the process was kind of predominantly a true crime critique.”

There’s a moment in Zodiac Killer Project in which Shackleton interrupts his narration to tell the viewer to “watch this” just before a motorcycle flies across the scene of an otherwise quiet intersection. It reminds me in some ways of John Smith’s famous short film The Girl Chewing Gum, which consists of 16mm footage of a busy London street, and in voiceover, we hear Smith appearing to direct all the actions of the passersby on screen.

“Certainly, The Girl Chewing Gum, and perhaps even more so The Black Tower were definitely films I was thinking about while constructing this one,” says Shackleton. “I think the thing I love most about those films – and all of John Smith's work – is the slipperiness of the relationship between narration and images. More to the point, though, the way Smith invites the viewer to participate in that relationship and often upturns your expectation of how the relationship is functioning. That was something I thought about a lot in how my narration in this should relate to the images that are playing underneath it. How do all these pieces fit together? The thing I landed on, the formal dynamic of the film, is a result of the order of events of its production.”

This saw Shackleton and his cinematographer Xenia Patricia shooting in Vallejo, California, then recording his voice-over while watching the footage back in London, and then filming brief inserts that reflect the tropes the voiceover calls to mind. “The hope in the edit was to put this all together in a way that allowed the viewer to intuit that order of events, so that you start to notice consciously or otherwise, that I'm watching the location footage with you, and that I'm able to respond to things that happen within it, but that I'm not watching the little b-roll inserts with you, I'm actually producing them with the force of my imagination.”

This slipperiness of the relationship between narration and construction creates and perhaps reveals the tensions inherent in non-fiction filmmaking, particularly where Shackleton’s narration forgoes the crunchier ethical commentary and can sometimes favour the glib or sarcastic. “I don't say anything in the film that I don't mean. So, on one hand, if people watch the film and come away disliking me – as some people do – that's fine and I can live with that. What has surprised me is the extent to which some people make a moral assessment of me as I appear in the film, purely through what I say as a figure in the film, not holding that alongside what the film is. On reflection, I think it's fair to question: why make the kind of uglier moral side of it the text and the more thoughtful moral side of it the subtext? There may well have been different choices to be made.”

Does the true crime genre have a responsibility to strike a better balance between those two aspects? “Yeah, I think there is a responsibility. I'm often surprised how significant the ethical lapses in true crime are because to me you have a really obvious license to explore different versions of the truth and question reality in such a way that allows you to do all your little dramatic gambits for the sake of entertainment while also clarifying, for your audience, what are actually known facts and what is speculation. I think I'm quite far from ethically scolding about these things. I’m quite permissive compared to a lot of people, and even then, most true crime shows just don't seem interested in doing what, to me, seems like the most minimal amount of work to invite the viewer into the terms of truth-making that it's engaged with.”

Zodiac Killer Project has its UK premiere at Edinburgh International Film Festival, and screens on 15, 18, 19 and 20 Aug at various venues