EIFF 2023: Babak Jalali on Fremont

This year's Edinburgh International Film Festival closes with Babak Jalali's Fremont. Jalali tells about his desire to make a film with empathy and compassion, but without the schmaltz

The city of Fremont in northern California is an innocuous place – quiet, everyday, nondescript. It is not, perhaps, a particularly cinematic place; or if it is, it is the cinema of Lady Bird and The Virgin Suicides, where the uniformity of American suburbia seeps into every frame. Yet Fremont has, in one way, made its mark in the sweeping expanse of the United States: its metropolitan area is home to the largest Afghan-American population in the country, waves of immigrants having arrived since the 1979 Soviet invasion. It is in this city, in the monochromatic world of Babak Jalali’s quirky, deadpan comedy Fremont, that Afghan translator Donya (played by newcomer Anaita Wali Zada) lives and works and doesn’t sleep, plagued by insomnia that punctuates her nights and bleeds into her days.

Stories of refuge and displacement have increasingly taken centre stage in recent years; from Ben Sharrock’s Limbo to Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee and Frank Berry’s Aisha, this new wave of cinema pushes back against endless news cycles, recovering the complex subjectivities of those caught – perhaps forever – between two impossible places. “I for sure didn’t want this to be an American Dream film, because I don’t believe in that,” says Jalali – the British-Iranian director is calling from LA, where he is staying briefly before returning to his home in London. “[But] there is a sense that: ‘OK, now I’m here. Or rather, I’m not there. How am I going to move forward with my life?’” Fremont’s Donya inhabits this exact liminality: her new home of Fremont is almost uncanny in its mundanity, the familiarity of the American suburbs made suddenly strange, while her old home of Kabul exists only as memory.

More than displaced in space, Donya is displaced in time, caught between past and future as her present – working in a fortune cookie factory, visiting her impassive psychiatrist (played by On Cinema’s Gregg Turkington) – takes on increasingly improbable proportions. Time in Fremont operates in a quietly paradoxical way: it creeps by with the eccentric monotony of a Jim Jarmusch film, even as the past suddenly drops back and the future hurtles forward. “I feel like I’m losing time,” a gentle Afghan cafe owner tells Donya on one of her visits there. All the characters in Fremont, from Donya’s displaced Afghan community to the quietly hunky mechanic she meets (The Bear’s Jeremy Allen White), are attempting to negotiate the slow ache of life passing them by, possibly forever.

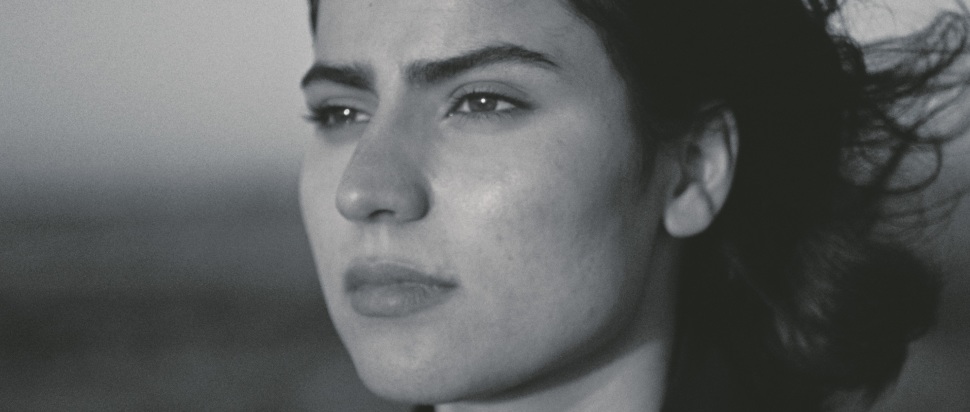

Fremont. Credit: Modern Films.

Yet Fremont, Jalali stresses, is a film as much about hope as it is about loss. Even Donya’s job working in the tedium of a fortune cookie factory speaks to a world that exists beyond hers, one that maybe hasn’t even happened yet, but that is within her grasp. “The idea for the fortune cookies came from my co-writer Carolina Cavalli,” Jalali says. “As a director, I was struck by the visuals, but for Carolina... what's written inside most fortune cookies is complete nonsense. But sometimes there are these things that linger. Most of all, what's written inside is about possibilities.”

The wide-open possibility of the future can be terrifying for anyone: it can be especially overwhelming when the past, and everything and everyone that have been left behind, still loom large. While Fremont was originally ready to film before the pandemic, its eventual shoot took place in 2022 after the reinstatement of the Taliban the previous summer; a weight that is rarely explicated but is writ large in Donya’s present. Throughout Fremont, Donya grapples constantly with her guilt – guilt at having left, guilt at having worked as a translator for the US army while in Kabul, despite there being no other work available to her – a heaviness that Jalali well understands.

“I was eight when I moved to London, and of course at eight, it's not a choice. No one said: ‘Hey, would you like to move to London?’” Jalali says. “And when I went back at the age of 22, my memories from when I was seven were far stronger than my memories of when I was 16. Because when I was in London, I wasn't clinging onto memories. But from the age of eight to 22, I thought about Iran constantly.”

The persistence of memory can be a double-edged sword – our only defence, perhaps, is the gentleness of those around us. Fremont was written, Jalali explains, during a time of particular political cruelty in the wake of Brexit, the 2016 American election, and the demonisation of refugees and vulnerable groups across the globe. Yet in Jalali’s film, characters treat each other with an understated, offbeat, yet strikingly deliberate kindness which works to undo, ever so slightly, the hostility emanating from their contexts and from themselves. “I didn't want it to be saccharine or cheesy,” Jalali says, “but I do think there is room for empathy and compassion without being sentimental.” It is, he explains, sometimes the only thing we have left in our arsenal. “I don't think this film is going to change the world,” he laughs. “But I think it is the only way I have to say something.”

Fremont closes the Edinburgh International Film Festival on 23 Jul and is released 15 Sep by Modern Films