Life After Prison: Solitary and America is Hard to See

The US is known for its high incarceration rate, locking up more people than anywhere else in the world. Two New York-based companies heading to the Fringe this summer linger on the question: what happens when they get out?

“At the other end of mass incarceration, you have mass reintegration,” says Blake Habermann, the co-creator of Solitary, a show that examines the lasting psychological effects of solitary confinement. “In the US, 80% of people who have been released have been in solitary confinement. And you can be put in solitary confinement regardless of what crime you have committed.” He pauses. “We really have to deal with the reality of what these people face.”

Both Solitary and Life Jacket Theatre’s show America Is Hard To See study this reality; the variations and complexities of it, the struggle for rehabilitation and the ever-present weight of a criminal sentence. Solitary focuses on the effects and after effects of incarcerated solitary confinement, while America Is Hard To See settles its gaze upon a different sort of imposed isolation – one that continues after the prisoner's release date. It's a verbatim piece of documentary theatre drawn from interviews with the inhabitants of Miracle Village, a community of sex offenders in Florida who are prevented, by strict state laws, from re-entering normal society.

Neither show offers any easy answers. "We're theatre-makers, not journalists," says Travis Russ, writer of America is Hard to See. "We're not interested in the truth; we're interested in multiple truths." Both plays aim to humanise the criminals at the heart of their stories – something Russ admits he initially struggled with. "[Our theatre company] is interested in people on the margins, and this idea floated to the surface... my first reaction was absolutely not, there's no way we're doing a show about that," he tells me. "The moment that thought crossed my mind, was the moment I knew we had to do the show. As theatre-makers, we have a responsibility to talk about the things we can't talk about in society. Theatre has a unique way to shed light on taboo topics."

'Beyond Words': humanising 'the criminal'

"We tried pretty explicitly not to make itabout one of the testimonials we read," says Habermann of the artistic process behind Solitary. "But the thing about them is that they're all so similar." Habermann read Charles Dickens' account of visiting a London prison in 1836, A Visit to Newgate, as part of his research; he was shocked by how similar Dickens' observations were to the testimonies of "a 17-year-old in solitary confinement in 2005. They say exactly the same things about what the experience is like. The medical documentation we read too – no matter the person, no matter the prison, after a certain amount of time, the same behaviours start to manifest."

This research led Habermann and co-creator Duane Cooper to realise they wanted to make Solitary about a universally applicable experience of confinement, rather than a single character's journey. "We didn't want to make it, you know, 'the story of Bill', or what Bill did," claims Habermann. "[We were looking at] the routine of prison, the behaviours," interjects Cooper, "and then we thought: can we show psychological deterioration through an object, as opposed to a person acting as if they were losing their mind?"

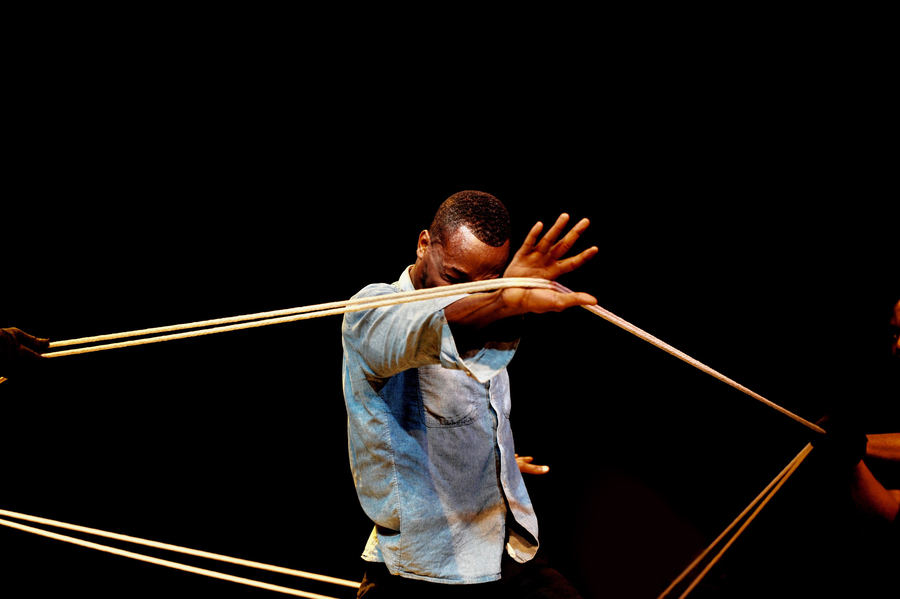

The object they chose to use was a rope. At various points in the play, it represents the walls of the unnamed character's cell, 'a portal through which he's entering something' and the internal 'state of his mind.' Solitary features no dialogue or speech, and relies entirely on mime, physical theatre, and the use of this one essential prop. The result is a show that arguably humanises its protagonist in a specific way, entirely different to what dialogue or narrative would be able to achieve. Certain moments Habermann and Cooper refer to are heartbreakingly symbolic.

"At a certain point, towards the end [of his time in solitary], he tears the rope down and ties it around him," says Habermann. "In the third act, when he's out in the world, he has the rope all wrapped around him. There's a scene where he's at a job interview, and while he's gesturing, the rope is seeping out from under his jacket. It's always with him."

Artistically, it was somewhat liberating, says Cooper, "not trying to come up with a clever turn of phrase to represent something; using a single object, using our bodies, to show what was happening rather than describing it – hopefully that makes it more impactful." The symbolic nature of the show's construction also allowed the piece to have more of a universal theme, "like a fable," explains Habermann. By virtue of focusing more on the feelings and experience of solitary confinement, rather than the details of one man and his crime, Solitary's criminal is much harder to judge. "We discussed at length, if he were to speak, what would he say?" says Habermann. "If we had dialogue, we would lose this fatalistic quality: we'd have to start thinking about who he is, what's his name, where are we and what happened."

Music

While America is Hard to See does feature spoken narrative, a huge part of the show revolves around music. The 90 minute play includes eighteen 'musical moments' sung by the cast members. Music was intrinsically woven into the story from the beginning, says Russ. "It's a key part of the narrative of this show. A lot of the men joined the choir of the pastor who invites them into her church – they sing and play instruments. We couldn't not include it."

But Russ also suggests that music is a powerful tool for a show that raises such difficult and troubling questions. The traditional Methodist hymns that the men sing are "hundreds of years old," Russ tells me, "And there's something about hearing these hymns sung by people who committed these types of crimes, in a play about this topic... Initially, when I heard the real men in Florida sing, my instant reaction was, 'you don't have a right to sing these songs'. And then again, once that thought floated across my mind, I questioned: who has the right to ask for forgiveness? What are the limits of forgiveness? And I just thought – that's the experience I want the audience to have. For them to recognise a hymn, that they have sung in church perhaps, and wonder: who is allowed to ask for God's grace and forgiveness?"

Singing is a universal expression of joy and togetherness; by singing, the men demonstrate a humanity that contradicts the nature of the actions they committed. It's a complicated and sensitive dynamic, but Russ says that's exactly why the play is necessary: "this is a problem in society, and until we talk about it, the problem is never going to be solved. We don't tell the audience how to feel, and we embrace the emotional confusion."

Moving forward

Russ maintains that "the men in this play have caused a lot of damage and hurt a lot of real people." Is rehabilitation possible?

"The answer is I don't know," he replies. "As a theatre-maker, I'm interested in the struggle to move forward – the struggle to rehabilitate oneself. As human beings, we are very complicated. It's a hard thing to deal with, but we have to open up the conversation to deal with this problem."

Solitary is entirely different in the sense that the individual's crime is never specified. Habermann and Cooper, however, also believe that the question of rehabilitation is an important conversation to have, and that we must examine how ex-convicts are treated once they leave the system.

"In the US, the idea of 'do the crime, do the time' is deeply conditioned into us," says Habermann. "The other side of that is that when you get out, you are still a second-class citizen. You don't have access to a lot of governmental services... you aren't able to get a lot of jobs. The ripples of [prison], the echoes of that – they're far worse than what we gain from punishing people [that way]."

Russ agrees. "A lot of the time, we're still treating people like criminals after they've done theirr time. If that's true, why aren't they still in jail?"

Solitary, Assembly Rooms (Powder Room), 1-24 Aug (not 12), 9.35pm, £8-11

America Is Hard To See, Underbelly Cowgate (Big Belly), 4-25 Aug (not 12), 7.45pm, £6.50-12