Dance Dance Revolution: The 2010s in Scottish Clubbing

As we enter a new decade, we look back on the last 10 years of Scotland's electronic music and club scene, with help from Optimo's Keith McIvor and Jonnie Wilkes, and Huntleys + Palmers' Andrew Thomson

It will come as a surprise to absolutely no one when I say that a lot can happen in ten years. In 2010, audio and video streams didn’t contribute towards chart position – that didn’t happen until 2014 and 2018 respectively – and people still listened to music on iPods; imagine that! Since then, the music industry has experienced significant changes.

Streaming has taken over as the lead method of consuming music, meaning artists often don’t make much money from their releases and instead rely on other avenues to sustain their careers. The traditional album release model has also become somewhat obsolete as output has increased and surprise releases have become the norm.

At the same time, physical products have been increasing in popularity. Vinyl has seen an unexpected resurgence over the last ten years and, in a recent report by the Recording Industry Association of America, it was predicted that vinyl would outsell CDs for the first time since 1986 by the end of 2019. The sales of cassettes also grew in the UK in the first half of last year, with almost double the amount sold over the same period in 2018.

With the Band(camp)

As demand for vinyl has increased, though, we also saw the collapse of major high street music chain HMV. And, while there are still plenty of record shops around (and HMV has since been revived in a smaller form), the increase in vinyl demand has meant that there has simply not been enough space for all these new records to be stocked. Countering this problem has been digital music platform Bandcamp, which has become an invaluable asset for labels and artists.

In 2019, one half of legendary Scottish DJ duo Optimo, Keith McIvor celebrated ten years of his Optimo Music label. Founded in 2009, the label has released music from a broad range of artists from Scotland and beyond. McIvor credits the personal element of Bandcamp as its most appealing factor. “It's a joyous way to buy music,” he says. “I was always selling digital music through all these other outlets but it was always somehow very faceless and at a distance, whereas there's something more tangible about Bandcamp.”

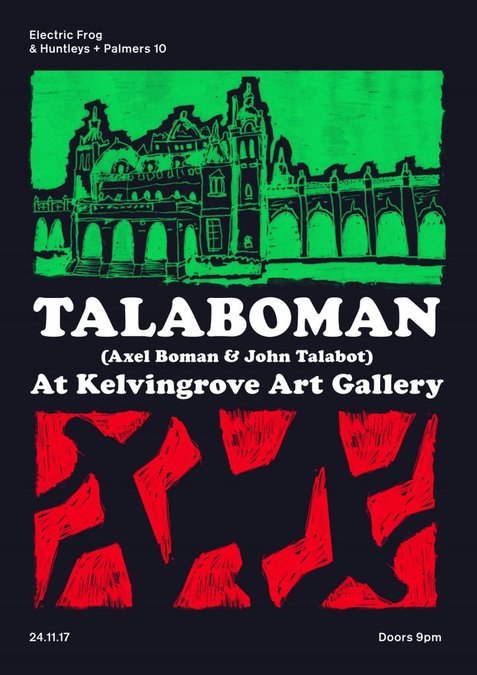

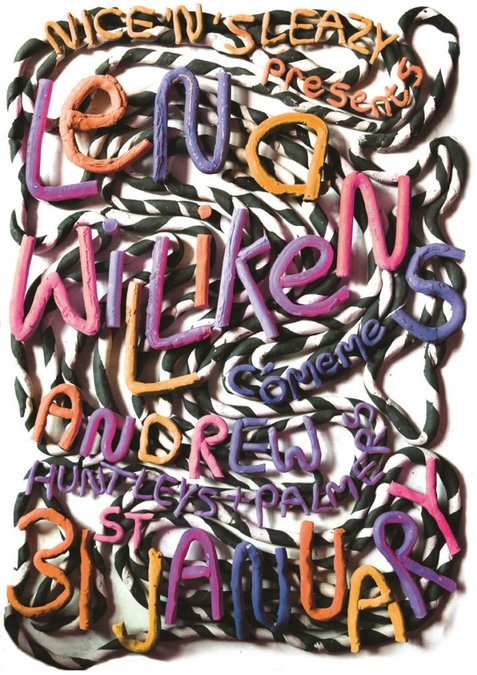

Another key record label in Scotland over the last ten years has been Huntleys + Palmers, founded in 2011 by Andrew Thomson. He agrees that Bandcamp has been an important platform for independent record labels over the last decade. “It's really encouraging when you see people on Bandcamp buying all the different releases, so it makes you feel like they're trusting you,” he says. “In the age of Spotify I think it's really nice that it's not really an algorithm, it's still people trusting humans in their taste.”

Lock Down Your Aerial

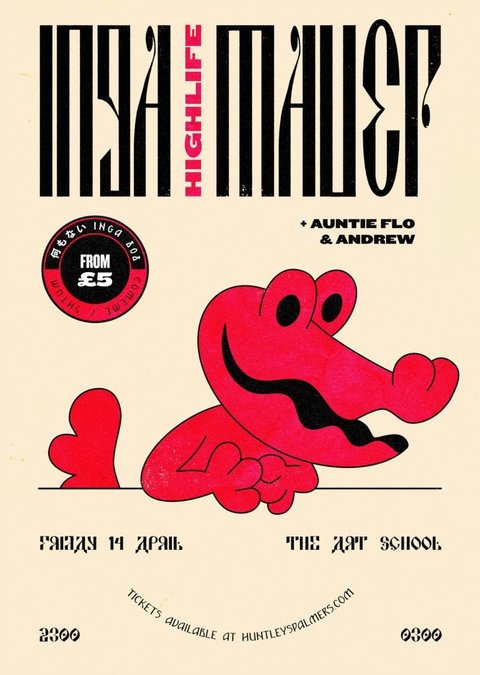

As well as celebrating ten years of his Highlife party series with Brian d’Souza, aka Auntie Flo, this year, Thomson recently announced the launch of his new Glasgow-based online radio station. Clyde Built Radio will begin broadcasting out of the Barras Market this month, with the intention to showcase Glasgow’s bright club scene.

In the last ten years there has been a boom in community radio stations, and just about every DJ nowadays has their own radio show. McIvor and Thomson have both had experience on stations like Rinse FM and NTS, and Thomson hopes to recreate that sense of community with his own station. “Something I've felt Glasgow is missing is being able to shine a spotlight on the scene, which is already very strong, but it almost feels like a well-known secret in some ways,” he says.

McIvor believes radio is a good method of showcasing the diversity of your musical taste as a DJ outside of a club setting. “It's always been part of our mission to turn people on to what we think is great no matter what genre it is,” he says. “So doing a radio show was pretty liberating because we could literally play whatever we wanted. It didn't have to be dance-focused.”

Stream If You Wanna Go Faster

It’s difficult to imagine, given how ingrained live-streaming has become in the electronic music community, but ten years ago Boiler Room was only just finding its feet. The online music broadcasting juggernaut was founded in March 2010 and has since gone on to become one of the biggest online platforms in the music industry.

While it obviously has its downsides, Boiler Room has allowed an array of previously unheard DJs and underrepresented music communities to reach a global audience. “I think, especially for people who live in places where they can't go to a club every week, it's a revelation,” says McIvor. The extent of its reach is something Thomson says he has noticed much more when DJing further afield.

“It allows people to be as far removed from what you would consider a sort of central hub… It's definitely opened up the scene a lot more,” says Thomson. “A good example is Sherelle. She just went viral and now she's got a Radio 1 show, through a really short clip of a spinback on a Boiler Room video… new faces can just get propelled and it would have taken them years to get recognition through traditional channels in the past.”

All I See Is Dollar Signs

This ability to achieve such rapid viral success, teamed with the surprising rise of EDM, has turned dance music into an international money-making machine. Leading the EDM brigade over the last ten years has been the likes of David Guetta, Skrillex, Diplo and Calvin Harris – all now multi-millionaire, multi-award-winning global superstar DJs.

At the highest level, DJ fees can reach the millions. Take Scotland’s own Calvin Harris for example: he was named the highest-paid DJ in the world by Forbes for six years in a row (2013-2018), and when he announced the extension of his Las Vegas residency at the Omnia nightclub in Caesars Palace into 2020, he was said to have signed a £200 million deal for 25 gigs – that’s £8 million per show.

Obviously, these kinds of fees aren’t offered to everyone and not even in their wildest dreams could most DJs imagine being paid millions per show. But even on a lower level, DJ fees have sky-rocketed and it has made it almost impossible for smaller promoters and clubs to book certain DJs. Part of this can also be attributed to the glamorisation of the DJ lifestyle through social media, particularly Instagram.

“It's only social by name, but there's nothing sociable about it,” says Thomson. “It makes people feel more isolated than involved.” The view portrayed on social media, too, is not one that’s entirely accurate. While it may seem all glitz and glamour, champagne and sunny beaches, touring can take its toll on many DJs.

“I think it can give a very false view because it's very seductive,” says McIvor. “I love what I do – it's the greatest job in the world – but there are downsides to it in the travelling side, the lack of sleep, mental health issues, and I think sometimes the Instagram side of things can gloss over that.”

A Little More Conversation

McIvor’s DJing partner Jonnie Wilkes opens up about his struggles with depression and addiction issues over the years, partially a result of the pressures of touring. He has now been sober and clean for two and a half years. “I do think that there's an intensity to the nature of our touring life, which some people manage better than others,” he says.

“I thought I managed it through drugs and alcohol for a long time when actually I wasn't managing it at all,” he continues. “I think it's great that people are talking about it and I think that it's really helpful for some people just to simply express it online or even the first step of declaring it. I think it's very brave.”

The sober lifestyle is something that has become much more normalised in DJ culture, even just over the last few years in particular, and rightly so. The nightlife community is often unfairly branded as one in which young people only participate in to drink or take drugs; a narrative that does a disservice to the passion and hard work of those involved in it. But the tides are shifting and clubbing is now more popular than ever.

However, with such a great deal of political uncertainty in the UK at the moment, it’s anybody’s guess where the music industry will go over the next decade. Judging by the trends of the last decade, we’re likely to see the interest in electronic music continue to grow and reach wider audiences, hopefully developing upon that sense of community it’s done so well to nurture over the last ten years.