Yan Ge on her debut English-language collection Elsewhere

Yan Ge introduces her debut English-language collection Elsewhere, a group of short stories hopping from Dublin to colonial-era Burma to ancient China

‘Elsewhere’ is rooted in absence, a location defined by where it is not; a word in search of something, an orientation that anticipates displacement. It is the perfect title for Chinese author Yan Ge’s much-awaited English language debut, a collection of nine short stories that somersault between modern-day Stockholm and ancient China, colonial-era Burma and post-Troubles Dublin, yet which all retain a fascination with negative space. The perfect title, however, didn’t come easily.

“I was annoyed by how different the stories were,” Yan says, recounting her arrival at Elsewhere. The collection is vibrant in its unpredictability, albeit haunted throughout with familiar echoes: these are ravenous tales about hungering bodies. A story about a group of writers feasting after the Sichuan earthquake gives way to a story about a marriage plagued by post-colonial ghosts. A story about negotiating autonomy in a lactating body (while dealing with “horrible literary men”) exists alongside an epic piece of “speculative historic fiction” about a power struggle between Confucian disciples. This last one, Hai, is over 100 pages long; it reads like a season of Succession via an ancient Chinese philosophy symposium. The inspiration for it? “Boris Johnson and Prime Minister's Questions on TV,” Yan laughs.

“When I sent this [collection] to my agent, it was called Nine Stories. He was like, ‘Nine Stories is not going to be OK.’ I kept pitching titles to him, and kept getting rejected. At one point I said, ‘Why don’t we just call it Elsewhere?’ This was me giving up,” Yan says. “He said, ‘Oh, I like that!’ I was like, ‘What?’”

Yan’s moment of frustration translated into a title of perfect resonance. “If somebody who grew up here read a story that took place in China, they’d say, ‘that’s elsewhere’. But to me, all the stories that took place here were my elsewhere,” she explains. “Elsewhere is dependent on who’s looking.”

Named one of China’s 20 future literary masters by People’s Literature, the oldest literary magazine in China, Yan has been “published for quite a while,” to borrow her understatement. But Elsewhere is her first work in English, a linguistic transition that promised an “enticing” opportunity for self-reinvention. “What intrigued me was what kind of writer I would become in this new language,” she says. “I had started to write in order to comply or rebel against the concept of the Chinese Yan Ge.” But English released her into “the wilderness; the pure excitement of being reborn as a new writer.”

Yan is a writer fascinated with writing – its intellectual practices, its social spheres, the contested processes of narrativising and translation. All nine stories in Elsewhere feature writers of some kind. “I’m not proud of it,” she says, laughing sheepishly. “It’s like giving in to your bad habits. I’ve been a writer since I was really young, so this is my one identity. I’m a person with really narrow interests, and I love literature and narratology.” In similar fashion to a character in the story Stockholm, Yan admits she quotes Foucault when drunk, then feels “embarrassed for being socially inappropriate”. When she went into labour, the book she brought with her was Jacques Rancière’s The Aesthetic Unconscious. “Philosophers, literary theories – those things genuinely soothe me. I’m not proud of it,” she repeats. “But in this particular collection, I completely gave in.”

But Yan’s stories are wild cards, necessary and seductive subversions of the canon. When Travelling in the Summer, a story spun from an itemised packing list written by academic Shen Kuo in the year 1095, was stylistically inspired by Marguerite Yourcenar’s Oriental Tales. But Yan reimagined Yourcenar’s Western Imagination of the Orient, and “gave it back”. During her MFA in creative writing at the University of East Anglia, this story received the following feedback: “I don’t know why I should care about a story that took place in ancient China.”

“I thought, challenge accepted.” Yan smiles. “So I wrote the Confucius story.”

Appropriately, Elsewhere explores translation as a process of approaching commonality on both a linguistic and political level: be it between women and men, East and West, writers and non-writers. Why this fixation on the gaps? “As somebody who writes fiction, I think I worship the unattainability of human communication,” Yan says. “That’s something I celebrate. Because if language was efficient enough to express ourselves – and I’m going to quote Confucius now – then we don’t need fiction.

“We need an image that is a bit blurred, a bit ambiguous, and then we interpret it.” Here returns that idea of traversing negative space: the work of reaching understanding, bridging the chasm between you and me, writer and reader, fictional milieu and a present place and time. “I really believe stories transcend language. I think those kinds of things, the miscommunications” – the way people are like two comets chasing each other, to quote a story in Elsewhere – “are quite beautiful.”

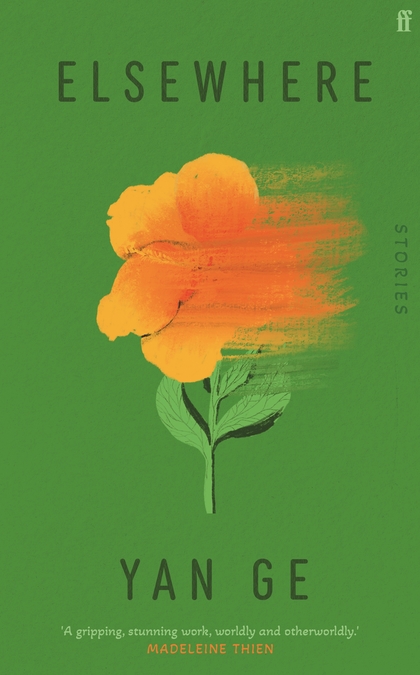

Elsewhere is out on 1 Jun with Faber