Universal stories: Scotland's translation boom

With Highlands-based publisher Sandstone Press winning the world's largest prize for literature in translation, Laura Waddell takes a dive into Scotland's success in the world of translation

Corks popped in the Highlands recently when Dingwall-based publisher Sandstone Press won this year’s Man Booker International Prize. Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi, translated by Marilyn Booth, is believed to be the first book by an Omani woman translated into English. The first Arabic book to win the Prize, it was rewarded for its rich, multi-generational portrayal of an extended family. The win has also shone a spotlight on the success of translation in Scotland, which is flourishing in a number of presses.

Sandstone Press

"The Man Booker International win has been an extraordinary experience for Sandstone," says Editorial Director Moira Forsyth, describing what happens when an indie publisher wins a big prize. "We had a ‘What if we win?’ plan in place, but it was still a shock to realise we must now put it into action! However, that happened instantly; the button pressed for a much larger print run complete with winner’s badge on the cover, the press release sent, social media managed, and sales monitored. The whole Sandstone team stepped up to the challenge with enthusiasm.

"Since then, the media coverage has been astonishing, full of praise for the book and its translation, and worldwide. We have exported to the Middle and Far East in quantities far beyond any of our previous sales in these territories. We’ve been touched by the many warm messages of congratulations we’ve received since the announcement, from across the publishing world, and indeed from our own authors."

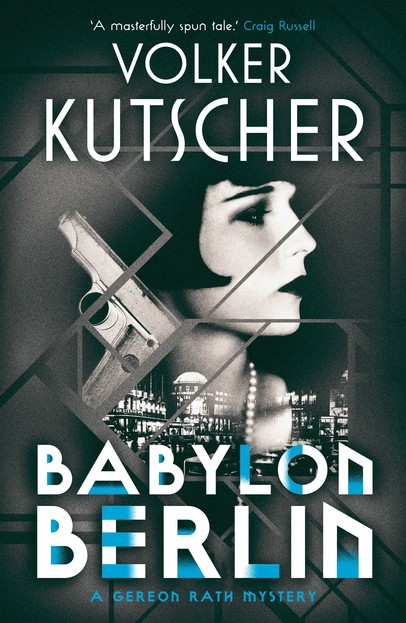

Yet Celestial Bodies is only the latest translated book Sandstone has had smash success with. "We have been publishing crime in translation for a number of years, and these have done well for us, both Jorn Lier Horst’s William Wisting series, and the Gereon Rath Mysteries by Volker Kutscher."

Readers might recognise Kutscher’s Babylon Berlin, the hit Sky TV show which also happens to be the most expensive non-English language drama series ever made. Sandstone’s bid for English language publishing rights paid off, with translation from German by Niall Seller, and the books have sold well.

Forsyth says the press will continue publishing in translation. "Sandstone has always had an international outlook, so we see translated work as integral to our list. Next year we’ll publish our first work of non-fiction in translation, Sleepless, by Norwegian author Anders Bortne."

Charco Press

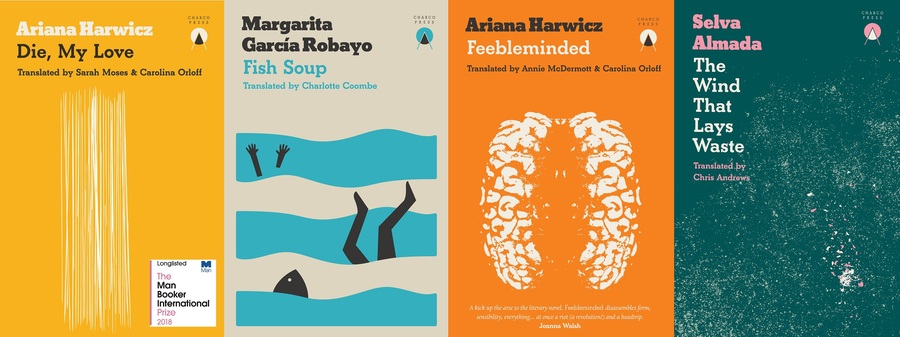

Sandstone aren’t alone in their Booker success. Last year Edinburgh-based Charco Press, dedicated to publishing Latin American authors, also hit the longlist. "It was a game changer," says Editorial Director Samuel McDowell. "Here we were – this brand new, unheard-of publisher up in Scotland. When one of the first books we ever published – Die, My Love by Argentinean author Ariana Harwicz – was listed for the most prestigious prize globally for works translated into English, it launched us onto the radars of a whole new world of readers. It also lent some immediate legitimacy to Charco within the industry itself. For us personally, it reinforced our view that there was some incredible writing talent out there waiting for readers here to discover."

Charco emerged in 2017 and have hit the ground running. "We looked at the breadth of incredible literature being produce by Latin American authors today, and looked at how little of it was being made available to readers over here, and decided that this needed to change. Plenty of these authors were being translated into other languages – why should UK readers be missing out?"

The buzz isn’t solely down to prize spotlights – sales have risen across the UK too in recent years, challenging the idea that translation is a niche book category of its own, but rather a portal into other stories from other places, genre and literary alike. This appetite clashes with a wider picture of xenophobia; Edinburgh International Book Festival, with a strong literature in translation strand, has in recent years struggled with Home Office rejection of visas and a number of writers unable to enter the UK to attend their own events.

McDowell speculates on the popular reception for translated books. "One could look at the current political climate as one reason – the rise of nationalism and populism, increased protectionism and the use of migration to foment fear and distrust of other people and cultures. A natural reaction to this by some is to want to reach out even more, to share and experience other cultures.

"As attitudes have started to change and support has increased, we have started to see growth in consumption of translated works, and translation starting to establish a new foothold. We are seeing more translated works being published, and more are being sold. The result? Readers now have far greater access to explore new and exciting authors. Stories, and storytelling, are universal. We should remember that. A good story does not respect where it was written or in what language – it will find its audience."

'The old rules don't apply anymore...'

Despite the pay-off of sourcing excellent books not yet available in English, as well as the extra effort there are additional costs in looking further afield, including financing the translation itself. Alongside grants from bodies such as the Arts Council in England and English PEN, Publishing Scotland’s Translation Fund, backed by Creative Scotland, is now in its fifth year and has helped publishers from a host of countries (including Greece, Croatia, Bulgaria, Estonia, Norway, Germany, France, Spain, and Italy) translate Scottish writers into other languages. Not only does translation build international cultural bridges between writers and readers, but reaching new markets adds to the stability of the Scottish publishing industry and grows appetite and opportunities for Scotland-based writers.

Vikki Reilly, Marketing Manager at Publishing Scotland, thinks the industry is in an era of change. "I feel we are at a time when certain old truisms in the book industry are crumbling, particularly on genres that [stereotypically] 'don’t sell': poetry, short story collections, and fiction in translation. I think a lot of this is due to the younger generation of booksellers, bloggers, those that work in the publishing industry, and publishing start-ups and micro-presses deciding that the old rules don’t apply anymore. It’s so exciting to see this ‘If we build it, they will come’ attitude when it comes to marketing, selling and community-building to readers.

"This is happening alongside, and is connected to, the increasing interest in publishing that is happening outside the Big Five and London – it all feeds into creating a growing confidence to do the things you’re not supposed to! And Scottish publishers are reaping the rewards of tapping into that fearlessness.

"Sandstone winning the Man Booker International, and their continued success with the Babylon Berlin series; Charco Press winning the [The British Book Awards] Scottish Small Press of the Year award; publishers like Vagabond Voices, Canongate and Polygon continuing to bring us new writing and new perspectives from across the world. It helps too that all this publishing is done with such visual panache as well; it more than stands alongside the publishing that comes from bigger houses on the bookshelves of retailers across the UK."

For a small country with a rich tradition of storytelling, it’s perhaps unsurprising Scotland is punching above its weight when it comes to translated literature, but none the less cheering.

sandstonepress.com / charcopress.com

You can also keep up to date with the latest in Scottish books with booksfromscotland.com