SPAM on making poetry cool again

SPAM Poetry are publishing some of Scotland and the UK’s best and brightest poets. Over Google doc, we have a chat about their origins, the internet and why Glasgow is the perfect home for poetry

What was the inception of SPAM?

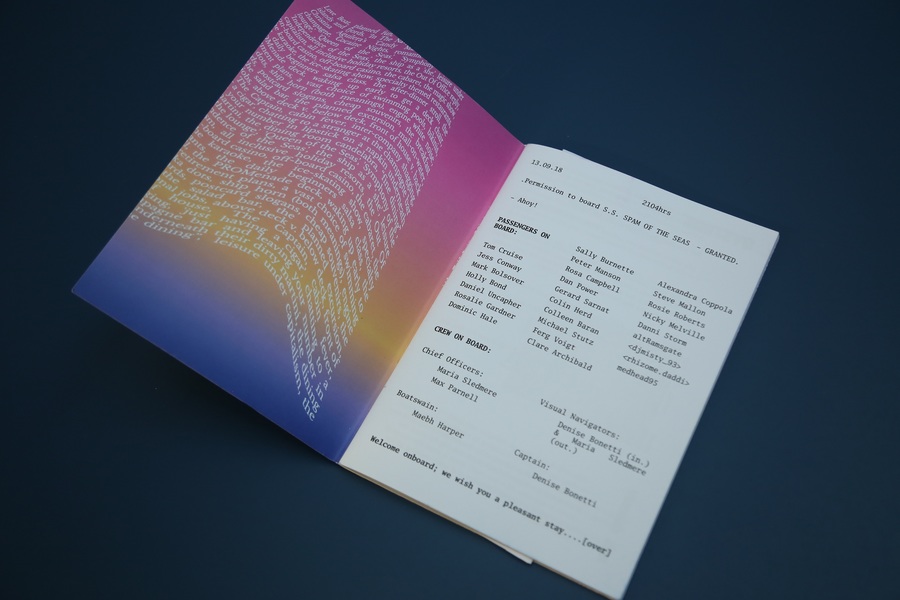

SPAM was founded in 2016 by Denise Bonetti and Maebh Harper, but the editorial team now consists of Denise, Max Parnell and Maria Sledmere. Denise and Max met studying English Literature at the University of Glasgow. Maria joined shortly after submitting work to our issue #2, Glitch, and Max in 2017 after we adopted his pamphlet of tasty meal deal poems, And no more being outdoors / And no more rain.

Denise and Maebh started SPAM because none of the poetry or literature publications they saw around resembled what living in the 21st century is actually like (i.e. immersed in internet ectoplasm). Doing or promoting good literature also always seemed to go hand in hand with taking oneself very seriously, which we weren’t comfortable with: we wanted to have our high theoretical cake and eat it with Love Island on mute while, like, Tom Raworth is rattling away on another open tab. So we thought – let’s just do it ourselves.

Did the name come from the literary subgenre spam poetry, or something else?

I guess the ethos is similar to creating poetry from whatever you get in your Junk inbox. We just loved the idea of starting a magazine for the leftover discourse, the uncategorised rubbish, the glitched or absurd, the things that normally get filtered out and no one has room for. Spam email is precisely that, but it’s also very much a post-internet concept, a corollary of information overload (which we’re all about).

It’s also a brand name, of course (ironically most of the editors are veggie), and as editors we’re all fascinated with today’s corporatespeak, the impersonal textual detritus that submerges absolutely everything. Calling ourselves SPAM is like eating late-capitalism from the inside out, or something. SPAM is this cheap 'ready-made' food with a complex political history, and maybe we’re reclaiming that to say something about millennials, the bloat of content and craving for cultural nutrition…

How has SPAM evolved over time into being one of the UK’s best poetry publishers?

OMG that’s so nice of you to say! I think sheer hard work [and] the lucky combination of having two Geminis and a Capricorn at the helm. Partly a commitment to doing things our own way: we could have bumped our prices or tried to go more mainstream, but we always wanted things to feel a little bit trashy, even while considering what we publish as high quality poetry.

We started off hemorrhaging Glasgow Uni library print credits and bribing a Byres Road cobbler to stitch together our first issue, and now we’re publishing poetry goddesses like Helen Charman and Daisy Lafarge, so it’s really nice to see how far we’ve come! I think initially it was the community we built around our launches, which always drew from poetry and music enthusiasts, that cemented a more local fan base. Since then, our online presence has developed and a lot of people now know us from the reviews content we publish, as much as from the press and the zines.

Have you seen a change from starting to SPAM to now, with how poetry is distributed and perceived?

In the three-plus years that SPAM has been going, we’ve seen the small press and indie publishing scene in the UK especially grow a lot. Publishers like Guillemot, HVTN, The 87 Press, Dostoyevsky Wannabe, Partus Press (to name a handful) are putting out amazing work. We like to be optimistic (our slogan is Make Poetry Cool Again – plz buy a tote) about the democratising of poetry via the internet, club nights and affordable publications.

It seems experimental poetry of a post-internet flavour is becoming much more critically and academically respected, in the sense that zines, blogs and small press pamphlets are even cropping up on university reading lists and academic journals. There is the cynical, monetising turn in Instagram poetry, but saying that, Instagram has always been a really important medium for us. And many of the best contemporary poets are on the ‘gram. Another thing we’ve noticed is the birth of more amazing poetry nights, from The 87 Press (London) to No Matter (Manchester) and our Edinburgh comrades at Just Not.

Why pamphlets?

We love zine culture, the urgency and play and subversiveness inherent to it. Plus the cognitive dissonance of seeing like Web 2.0 architectures/aesthetics reproduced on a lo-fi, black-and-white page. Pamphlets are so easy to swap and distribute, they become a kind of conduit for new friendships, collaborations and moments in time. We wanted our press to be affordable, while publishing quality and challenging works. There’s something about the “timeliness” of the pamphlet that feels post-internet, but also the sense that as an IRL object it’s a cleaving back of thought from the endless streams of the virtual.

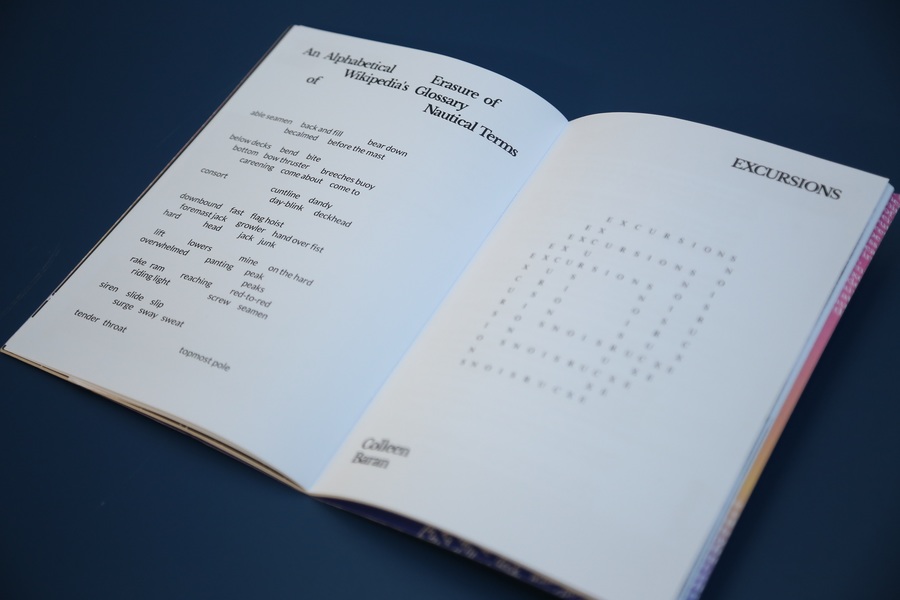

We believe that value is inherent to the poems we publish, but also the pamphlet can itself be a beautiful object: some of our favourite designs so far have included Daisy Lafarge’s capriccio (designed by Ane Lopez), Sam Riviere’s Darken PDF, Ryan Jarvis’ Tesseract Life and Anna Danielewicz’s An orca is way too big to attach, unless as a JPEG.

You’re based all round the UK but I want to ask about Glasgow. Do you think there’s a reason why there’s such a flourishing indie literary scene?

Glasgow is, as everyone says, the perfect combination of big enough and small enough: cosy enough to foster a community around arts projects, but big enough that you can get decent venues and outlets for your work. Even when you see the same faces, the scene still feels dynamic. For us, the English Literature and Creative Writing departments at the University of Glasgow have been a kind of hub for meeting like-minded folk, but also just our mutual involvement in the music scene here has helped make that natural cultural crossover (Denise, Maria and Max are/have been nightclub managers, music journalists and musicians themselves).

There’s always been a DIY spirit in Glasgow, completely apart from its institutions, and we like to think SPAM is built on that bedrock. Nobody takes themselves too seriously here, which can’t be said for all avant-garde poetry scenes and it’s nice to feel the warmly abrasive bath of Glasgow humour sometimes (academia by day, Wetherspoons by night – both with varying degrees of irony).

You say that “it’s time for poetry to enter the post-internet age.” Do you think poetry has done that yet?

What is time? What is poetry? What is the post-internet?

There’s a long-read in The New Yorker from a few years back called ‘Post-Internet Poetry Comes of Age’. More recently, a lot of controversy and backlash has come out of the alt-lit scene and Kenneth Goldsmith’s “uncreative writing”: the way its use can, for example, be an abuse of privilege. Part of our interest in the post-internet’s endurance as a literary mode and ontology is the ethical questioning that arises from this way of being. We’re not just interested in flarfy remix poems; we also want to provide a space for serious creative-critical interrogation of where we are in the world right now, as networked, mediated and desiring beings but also bodies still defined by class, race, gender, geography, (dis)ability and sexuality.

Providing an online space for essays and critical discussion has helped develop that, but we’ve also always tried to avoid our publication output weighing too heavily on like indulgent, “~fascinating textual junkspace~” as I think Sophie Collins once put it. Flirting with the weird, facilitating formal experimentation and collaging online detritus around lyric poetry has, we feel, always involved political gestures of value, dissent and challenging aesthetic hierarchies. Making memes is a mode of study, of processing the affective and tonal afterglow of the discourse we encounter at various levels.

Basically, we see ourselves as belonging to the resistant space, sociality and “play” of zine culture (whose heroes are surely punk, transfeminism and queer communities) and the confessional, disseminating and emojifying (lol) force of the tumblr/ LiveJournal/ MySpace/ MSN generation. As Colin Herd says, ‘The embarrassment of this poem is this: / We forgot for a while how to be sweet and funny’. To even claim the post-internet mantle is embarrassing! It’s like, Denise, Maria and Max – such nerds! But we think the outcome, as much as the gesture, has produced something sweet and funny.

Do you think the internet democratises poetry?

Part of SPAM’s ambition is to interrogate the very platforms in which we now think and communicate by kind of inhabiting them from within, like Kafka’s mole. Since we believe that the condition of late-modernity is now inherently post-internet, in that there is no “unthinking” our ubiquitous enmeshment within the online world, it’s tricky to know whether you are stuck in the feedback loops of The Algorithm or whether you’ve built up an actual community.

But our general oscillations between the virtual and IRL (through zine fairs, launches and the like) seem to suggest there is genuine love, care, friendship and interest there. At least for as long as these structures and technologies are present in our lives, we’ve got to navigate those oscillating modes of community. Post-internet poetry, at least the kind we’re interested in, acknowledges and dramatises our enmeshment with technology (which, since the first cave painting used to record a thought, was always already), while throwing critical light on its implications – ethical, aesthetic or otherwise. Often this criticism happens in the very registers that the internet fosters: for instance irony, parody, earnest confession and the funhouse games of the “meta”.

Do you see a similarity between the performative characters we perform on social media and the performative characters of poets, for example, both use specific language to communicate performative emotions?

Yes, there is definitely a lot of validity in that. It’s why we’re still wedded to the idea of the “lyric”, a feature of which is often using the kind of iterative force of poetry to move towards these extreme emotions. For example, Sylvia Plath’s ‘Lady Lazarus’: I mean she would have a very beautiful and dramatic tumblr, right? Gifs of her wild red hair.

What we’ve noticed in our submissions is many poets capitalising on the virtual infrastructures that invite that performative mode of speech (YouTube comments or TripAdvisor reviews, for instance) to communicate complex, difficult or ambiguous emotions and perspectives. There is also a funny A.I. twist to this of course; the idea that through all our performative emotions, a computer can then “perform” your consciousness back to you, in some sense. What does that mean for poetry, the Romantic “I” and the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (ol’ Wordsworth)? Dan Power’s SPAMphlet, Predictive Text Poems, is a kind of exploration of that: the poetic self refracted through the feedback loops of its own predictability.

Do you think the internet has made it impossible to write a poem without irony?

Given some of the very sweet and endearing submissions we got for issue #7 (Prom Date), we would say no. As Weyes Blood, Maria’s most-played artist on her 2019 Spotify, says, “true love is making a comeback”. Having said that, can you really write about a rose now without falling into a viral, ironic, Steinian loop? Crispin Best is a good example of a poet whose work often seems painfully sincere but there are all these like “slant” ironies at play there.

Having said that, there are different kinds of irony, right, it’s not all fun and memes. It can be real feeling! There’s this bit of graffiti on the boarded remains of the O2 ABC building: SHALL WE LEAVE THE GIG AND GET ON THE NIGHT BUS? It’s like a poem someone texted right before everything collapsed around them.