Ryan Gilbey on his new queer cinema book It Used to Be Witches

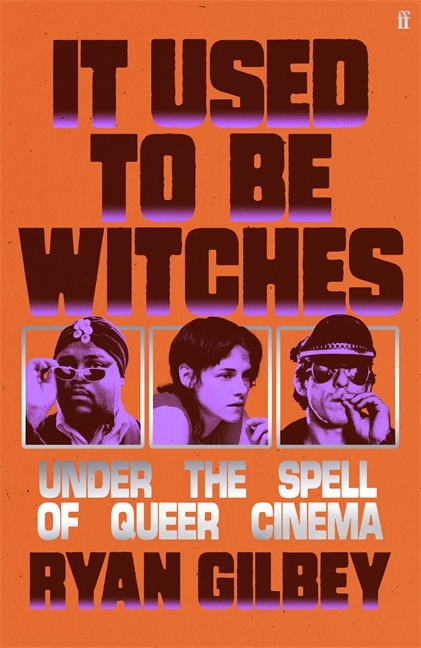

Film critic Ryan Gilbey talks to us about It Used to Be Witches, his playful new study of queer cinema history blending personal memoir, critical analysis and insightful new interviews with an eclectic ensemble of queer filmmakers

Ryan Gilbey is feeling like a poacher turned gamekeeper. He’s fresh from filing an interview this morning for The Guardian, where he’ll often be found writing some of the most insightful interviews in British film journalism. This afternoon, however, he’s on the other side of the Zoom link to discuss It Used to Be Witches, his dazzling new book on queer cinema, and he seems a little bit at sea.

“I always have my pre-interview rituals,” Gilbey tells me from his flat in North London. “It’s like, cram, cram, cram, and then for the last hour before the interview, I'll write down all my questions. And today I was like, What do I do? I don't know what to cram on?”

He shouldn’t have worried, I tell him. After all, a significant chunk of It Used to Be Witches is memoir; he’s been cramming all his life.

The idea for the book initially came from Faber, with whom Gilbey had published It Don’t Worry Me, his crackerjack critical appraisal of ten key filmmakers from the New Hollywood era. Gilbey initially jumped at the proposal, but when he sat down to write it, he was hit by a wave of impostor syndrome. His cheif concern was his queer credentuals. As detailed in the book, Gilbey knew he was gay from a young age (“As a child, he felt fizzy thinking about other boys, long before he acquired the language to express that – or the wisdom not to,” Gilbey writes of himself in third person in the opening chapter). He even came out in his teens, but then fell into two successive romantic relationships with female friends, before finally coming out for a second time, aged 41. “I thought, I'm not gay enough,” says Gilbey, “I was in straight relationships for two decades. I've got three kids. How can I write a book like this?”

He also struggled with the shape the book would take. “I remember saying to my editor, ‘Well, obviously the form has to be queer. It can't just be about queer cinema. The idea of doing another book like It Don't Worry Me, choosing a set number of directors and then going through them one by one – no, that would be crushing.”

Much time was spent mulling over this form (“I had some real Alan Partridge brainstorming sessions”) until he struck on the notion that this crisis he was feeling, all these worries about his own queer identity, should be part of it. “I was like, OK, I can't think of any books where it's about someone who's actually insecure about how queer they are. So instead of the roadblock, my insecurity became the vehicle to drive the book.”

It Used to Be Witches opens in Venice, with Gilbey arriving in that floating city to deliver some lectures on cinema to students as part of an art history course, and him being mortified when he realises the film clips he’s about to screen over the next few days are really fucking gay. “I really was having that crisis,” he explains, “and it was fascinating to realise that all those feelings of shame were still there. I was like, ‘What will the students be thinking about me when I show this clip from Nighthawks or this clip from The Watermelon Woman? Will they be shocked? Will they think I'm trying to indoctrinate them?’ I was feeling all that internalised homophobia, all the stuff that we were told about ourselves in the 80s, 90s, and, well, still are today.”

Throughout the book, Gilbey returns to similar moments of gay panic. Some are traumatic, like when he recalls watching TV with his parents as Tom Robinson belted out his punky queer anthem Glad to Be Gay, and feeling a mix of shame and elation. And some comic, like a cringe inducing episode where he tries to make a pass at a legendary queer director at a junket, only to bottle it at the last minute. But as the book progresses, there’s a sense that the actual act of writing this history of queer cinema while also reckoning with his queer biography has helped Gilbey become more comfortable in his skin, as exemplified the his narrator's voice shifting subtly from third person to first person.

Feelings of queer inadequacy comes up, too, in several of the probing but playful interviews woven throughout the book. As a journalist, Gilbey usually doesn’t have much truck for writers who insert themselves in their pieces (“I don't have a lot of patience with journalists who mention their kids in the first paragraph of every interview,” he laughs). But as he was telling the story of queer cinema through a personal prism, he wanted the reader to feel they were in the room with his interviewees, and could feel his awkwardness, like when trans filmmaker Campbell X teases him for being too hetronormative. “I was overjoyed when Campbell X called me out,” recalls Gilbey, “him saying, ‘Oh God, you're married with kids, aren't you? You should be out cruising’.”

Elsewhere, though, he was surprised to find that many of these wonderful queer filmmakers had similar feelings of self-doubt. “Like Desiree Akhavan, for instance,” suggests Gilbey. “She says she’s concernd about not being the right sort of gay because she doesn't like camp humour and can't stand how ugly the rainbow flag is, or then Andrew Haigh being told by younger queer audiences he's doing gayness wrong. I suddenly found all these echoes of my insecurities in all these great directors.”

One of the chief joys of It Used to Be Witches is how leftfield it is, not just in its inventive hybrid form, but in Gilbey’s choice to shine a torch in the less obvious corners of the queer film canon. “There's always a pressure to be exhaustive, to cover every single film, which I had to dispel,” he explains. “When I was able to shake that off, I could actively exclude certain things. Like The Wizard of Oz, it gets one mention, I think, and Happy Together only gets one mention. I love both those films, but I didn't want to feel I was going over well-trodden ground. Whereas Peter Strickland's film Night Voltage hasn't even been made, and it gets practically a whole chapter.”

Avoiding the obvious applies to the filmmakers he focuses on, too. The major auteurs of New Queer Cinema of the 90s are only mentioned fleetingly, for example. “I felt like I wanted people like Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant and John Cameron Mitchell to be like the tourist landmarks of Paris in Jacques Tati’s Playtime – you only see them reflected,” Gilbey explains. This leaves room for less celebrated figures like Elizabeth Purchell (Ask Any Buddy), Lyle Kash (Death and Bowling) and Stephen Winter (Chocolate Babies) to step into the spotlight and share their experiences.

Gilbey's catholic taste and vast knowledge of film history also allow him to take fascinating intellectual leaps and create surprising links between movies. He talks me through one of the elaborate dot-to-dots in the book that takes readers from Paul Morrissey’s 1970s queer touchstone Trash right up to Rose Glass’s lesbian crime drama Love Lies Bleeding: “Well I knew I wanted to write about Trash, and that got me writing about Holly Woodlawn. And I was like, ‘Oh, Peter Strickland directed her in his short, that's a good way into his films.’ And then, Oh yeah, my friend Ben said, 'What is it with Peter Strickland? He’s the British James Franco.' And that got me thinking, 'OK, I need to write about Franco. Oh, shit, I know Justin Kelly, he directed James Franco in two gay films [I Am Michael, King Cobra],' and then from Kelly getting into Kristen Stewart's body of work.” It seems simple when he says it out loud, but it’s bravado stuff on the page.

It Used to Be Witches is a splendid book, but being a critic himself, Gilbey has already imagined the bad reviews in his head. “I was stressing for a long time, going, ‘OK, I know what everyone's going to say about this. They’re going to say this falls between two stools. It's not filmy enough for a film book, and it's not memoir enough for a memoir.” It dawns on him, though, that’s a very normie, binary mindset. “I started thinking, ‘Hmm, between two stools? Maybe that's not so bad. That would be a very queer place to be, right?”

It Used to Be Witches is published 5 Jun by Faber

It Used to Be Witches talks and events:

4 Jun, Foyles Charing Cross Rd, London

9 Jun, Barbican, London – End of the Century screening

12 Jun, Margate Bookshop

15 Jun, Cinema Museum, London

16 Jun, Five Leaves Bookshop, Nottingham

18 Jun, The Garden Cinema, London – The Duke of Burgundy screening plus Q&A with Peter Strickland

27 Jun, Waterstones, Bristol Galleries

14 Jul, BFI Southbank, Reuben Library, London