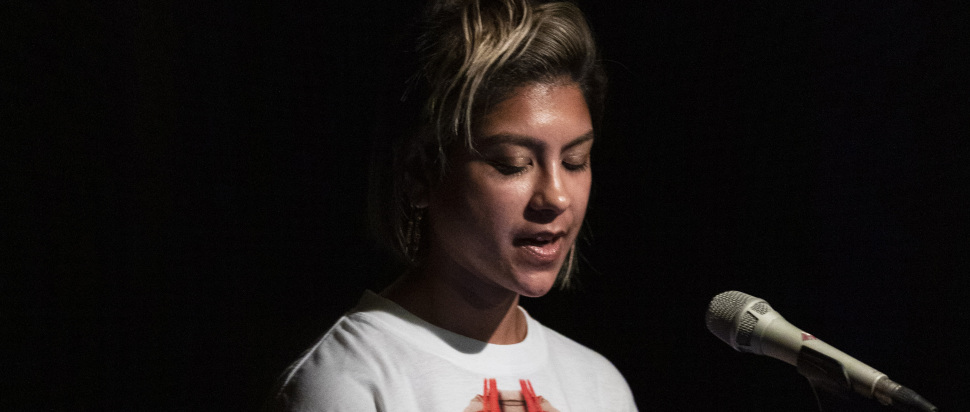

Nisha Ramayya on her new poetry collection Fantasia

We talk with poet and academic Nisha Ramayya about her latest poetry collection Fantasia, and the constellation of influences and touchstones that inform her practice

Let’s begin at the end: Fantasia concludes with acknowledgements that are a wonderful survey of the collection’s fantastical ‘experiments’, from close friends to a range of influences like Édouard Glissant and Don Cherry. The artist Moki Cherry – Don’s wife and another acknowledged name – once called fantasy a "very important word". What does the word mean to you?

[The acknowledgements] are the essential coordinates of Fantasia: everything begins and ends with the people in there. With Moki, I was struck by the dream she and Don had to create a space for people to come together, make music together and raise children together. There was no distinction between art and life. We all dream – whether we’re dreaming about possible futures or trying to rewrite the past – and it can be incredibly powerful when we put our dreams together. Ultimately, that's what Fantasia represents: an interplay between the spontaneity and intent that fantasy allows.

The collection balances being thoroughly outward-looking yet also strikingly intimate. What aspects of yourself do you find you’ve claimed, reclaimed or even renounced through working on it?

I was born in Aberdeen, but my parents moved back to India with me for two years and then we moved back to Aberdeen, and then Glasgow. Sometimes people would say, "Oh, where's Scotland [in your work]? It's all about India;" and other people would say, "Oh, you don't sound Scottish." Like with my first book, States of the Body Produced by Love, [although Fantasia’s] not autobiographical, it still comes from my experiences as well as an exploration of history that’s mediated through family, Indian, and colonial history.

I’d been trying to find ways to form my own relationship with India, whether that was through particular figures or texts I was translating from Sanskrit to English. But, the more I did this, the more I was coming up against things that I didn't want to claim and, instead, wanted to denounce. Then, I found the work of Fred Moten and I had a real falling in love moment. He helped me understand I needed to break away from this trap of either having to claim or denunciate a cultural background. There was this other model that was much more about a social life and the possibility that we can still form these unruly, unwieldy, weird shapes together.

How has being part of the academy informed your writing and the ways in which you listen?

Well, you’ll be familiar with the state of the higher education sector at the moment: the humanities in particular have been quite actively decimated by the Tories and by managers who run universities like businesses; [meanwhile], students have been subjected to some particularly punitive treatment by institutions that [should] protect and educate them. My academic practice has mostly become centred around trying to figure out how we can do something within these exclusionary and violent structures – how can we create little bubbles of real thought and support? People have an image of teaching as imparting knowledge. That's not it. Really, [it’s about] learning how to listen and letting the silence in.

I love the tension you’ve underscored here – of sound and silence, of independence and interdependence, of being part of something but also resisting it – as it feels key to reading Fantasia. The way you figure musician Alice Coltrane throughout the collection feels central to this. What drew you to Coltrane?

What I found interesting is the way that Alice [initially] figured herself as being in service to John, to her children and, later on, to her spiritual community. She had this extreme modesty: she stopped playing for a while after John died, but she started playing again with his bandmates [a few years later]. Then, she went on a trip to India and underwent [a series of] revelations. When she came back, she set up the ashram, became a swamini and started experimenting, doing things that no one else was doing musically. With Alice, there was this mix of a private practice – her spiritual austerities – and a collective practice. I started to wonder about what it would be like to be a swamini and to be elevated in this way – because when you're put on a platform, you're also set at a remove.

And what drew you to Star Trek – which is also given an honourable mention in Fantasia’s acknowledgements(!)?

I like sci-fi but I came late to Star Trek: it was during the first lockdown. And – even though the first few series are really appalling politically – I really did love the notion of the Enterprise. The symbolic notion of the Enterprise is: this requires work. There is labour involved in maintaining this vision, this social life, and we have to figure out ways of doing this together. And so, with Fantasia, I wanted to see what it would be like to include a range of work without making it enter a churn where it just becomes the same; to be the Enterprise, not the Borg!

Fantasia is out now via Granta. Ramayya will be appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 14 Aug at 6pm and 15 Aug at 5pm