Moshtari Hilal on her debut book Ugliness

We speak with Afghan-German writer Moshtari Hilal about her book Ugliness, and the politics of how beauty is constructed

"I like to talk about beauty and ugliness in terms of assimilation, rather than self optimisation," Moshtari Hilal comments on her debut book Ugliness, which has recently been translated into English from its original German. Composed of poetry, essays and visual art, Ugliness defies categorisation. It is at once autobiographical work, charting Hilal’s awareness and subsequent policing of her own ugliness, but it also traces the construction of ugliness and beauty as political tools to delineate the line between belonging and isolation. The text collapses time and geographies, the personal and the public, pain and pleasure – not to tell us what ugliness is but to reveal its power in dictating our social and material conditions.

“I found it very important to link personal intimate moments of self-hate with the language of criminalisation, assimilation, othering and colonialism. Because that is where it comes from,” Hilal tells me. She fuses her own experience of ugliness, deeply shaped by the experience of growing up in Germany as an Afghan immigrant, with the history of ugliness as a social construct. The chapter on noses, titled Nasal Analysis, opens with a brief history on the origins of rhinoplasty and its founder, Jacques Joseph, a German-Jewish doctor who claimed that those who opted for surgically altering their bodies could 'become happier in life by attaining a normal or ideal appearance.' This is immediately followed by a personal excerpt describing the long noses shared by the women of Hilal’s family, and the relentless criticism they experienced because of it. Hilal’s deft traversing between the historical and the intimate blurs the boundaries of linear chronology. For Hilal, it is clear that ugliness is a shared embodied legacy, where our insecurities are not individual or even personal.

Yet there is no solace to be found in beauty. The process of beautification, so often depicted in mainstream (usually Western) film and books as something gentle and passive, and referred to euphemistically as a ‘makeover’ or ‘glow-up’ is truthfully described by Hilal as a violent and tortuous process. The chapter of the book focussed on hair removal reads like a horror show; detailed descriptions of razors, blades, bleach and blood abound. Hilal smiles at this comparison.

“I wanted to tell the story of beauty as something horrible and violent, rather than innocent or passive,” she says. “Beauty is not just something that passively exists. It is violently constructed.” Beauty is also, Hilal notes, an ephemeral concept which requires daily investment of time and material resources for its upkeep. “The power of beauty is its role in disciplining our everyday routines and behaviours,” she says, observing how the COVID lockdown presented a crisis to beauty. “People could not maintain their beauty practices – either their hair grew or their nail extensions became too long,” she says. “It was like a reverse Cinderella effect. The upkeep and promise of beauty was no longer a truth you could hide.”

Although Ugliness is an indictment of the social manipulation of aesthetics, Hilal does not place direct blame on any single individual or group for reproducing and manipulating these hierarchies. The poetic interventions woven into the text reflect on her childhood encounters with the women in her family, particularly her aunts. “Most of the people policing my looks were aunts, because they understood that you are in a cultural setting where your value is linked to your looks,” she explains. Rather than casting anger or shame, Hilal uses poetry to recall these moments with deep tenderness and sensitivity. Although theoretically rigorous, Ugliness is also characterised by a profound sense of longing – longing for better, longing for more and longing for change.

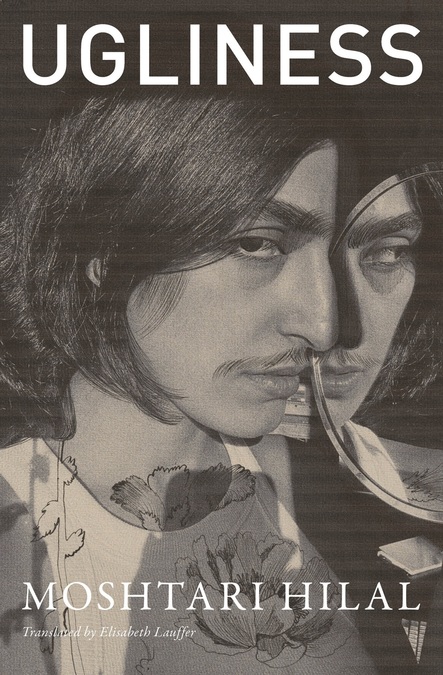

Up until recently, Hilal’s interrogation of ugliness has been through her visual artistic practice. She distorts her own image by enlarging her facial features, usually her nose, to grotesque proportions or adorns her face with a thick moustache or unibrow. These anatomical visual studies punctuate the text, giving form, shape and colour to Hilal's intimate insecurities. But they also serve another purpose. Hilal was clear that she did not want to reproduce historic studies of racialised bodies, and so reproduced them in her own image.

“Everytime we scrutinise ourselves or self-discipline our bodies, it is never just about us,” she explains. “We exist in and reproduce a tradition of dehumanisation.” Through her self portraits, Hilal extends the invitation for us to locate ourselves in the tradition of ugliness, and question how we might reproduce it by both judging ourselves and others. “I want the reader to feel like they are part of the research. Research is bound with memory, and I wanted to create that experience of familiarity.”

To read Ugliness is to confront the twin myths of ugliness and beauty. This is the truth we already embody but will not name. The power of Hilal’s work is that she poses deeply threatening questions with great care. “Why do we need the ugly?” she asks. “Why do we fear them?”

Ugliness is out on 11 Feb with New Vessel Press