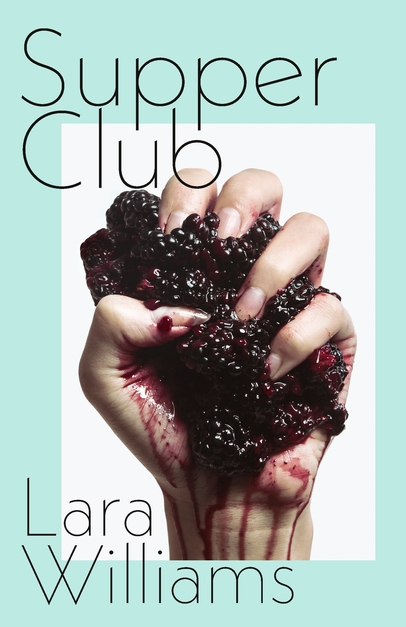

Lara Williams on her debut novel Supper Club

Lara Williams' debut novel is about taking up space, particularly bodily space, subverting the expectation that women need to shrink themselves down. We speak to Williams about writing Supper Club, gross food and abject bodies

Move over Chuck Palahniuk, there’s a new underground club in town. In Lara Williams’ debut novel Supper Club, Roberta, close to 30 and in a dead-end job, starts a supper club with a group of women, all fed up and trying to reckon with their respective pasts. They meet irregularly to cook together, eat until they vomit, take enough drugs to tranquilise a horse and dance the night away in the hopes of finding a catharsis to their daily boredom.

The club and Williams’ book are about taking up space, particularly bodily space, exploring the expectation that women need to shrink themselves down, as well as ideas of gendered power dynamics, friendship and anger.

“I knew I wanted to write something about women taking up space and thinking as broadly as possible about that: about appetite and taking up space and what those things mean,” recalls Williams. “The other thing I was thinking of was transgression and what it means to lean into something that might make you feel repressed or anxious. I have this weird theory that something that would help me overcome my shyness would be joining an improv class. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for years but I haven’t actually done because I think I’d be devastated to find out it didn’t work. I was thinking about this idea of leaning into something to a ridiculous extent and reaching a level of neutrality through that behaviour.”

Williams first came up with the idea of the supper club as the novel’s central idea and built her characters and narrative around that. “I wanted to do a first person voice – I thought third person would give it too much of a removal of personality. So, I knew it had to be a central protagonist.”

Roberta is that central protagonist, a sympathetic, often frustrating millennial woman who’s a little lost when we meet her. In flashbacks to Roberta’s past, we start to piece together why she is the way she is and the trauma she’s carrying inside her, the catalyst for the supper club. “When I started writing the primary timeline, where we see Roberta at university, it was me getting to know the character and exploring the things that might make somebody crave that kind of transgressive experience,” explains Williams. “I wanted to set some of it at university because I was quite conscious of that being a vulnerable time. I come from a smaller town and that experience of moving to a city is quite an overwhelming or dizzying one. I wanted to characterise that, and also because it’s a very definite moment when you enter adulthood. I wanted to ask what it means to go into that as a woman.

“I was also mindful of the narrative being focused on specific, individual stories, particularly Roberta’s story,” she continues. “So, one manifestation of trauma over a decade. There are ten years between the two timelines and she’s still reckoning with trauma and hasn’t really openly dealt with it or acknowledged it until she has that feeling of sisterhood and support and compassion. There’s no crystallizing moment of resolution: it goes away for a bit and then goes away for a bit and then comes back.”

A lot of the issues Williams explores in the book are very nuanced; was she careful about generalisations? “I was very conscious of taking an intersectional approach to it and thinking about my experience being wildly unrepresentative of other people’s experiences. That was something I wanted to dignify. The story is told through Roberta’s voice. Everything is filtered through her experience and her understanding of other people’s experiences. That was something I was conscious of because I can’t speak for other people outside my experience. I can just filter my understanding of it in the same way Roberta can filter her understanding of it.”

In the novel, Williams characterises that trauma through Roberta’s relationship to food and her body. “In the food sections, I was interested in taking up space in a meticulous way on the page and how I could take up space as an author, making the reader stay with me through that level of meticulous detail,” Williams notes. “I feel like that’s a slightly more male writing tendency, to go into the level of detail and almost test the reader’s ability to stick with that meticulous, methodical detail.

“I was also interested in the methodical elements of cooking. Cooking is something I find quite soothing and something that forces me to slow down. It’s work that involves using my body in a pleasurable way, so I was interested in characterising that. I also wanted to draw links between Roberta’s state of mind and different recipes. There’s a Thai red curry recipe and I used quite a simplified and anglicised version of what the recipe should be and I like the idea of it being a domestic and self-satisfied recipe, something you’d make to tell yourself that you’re at a good point in your life. But it’s also a little thin.”

While so much food writing fetishises food, in Supper Club food is gross and enjoyable in its unpleasantness. “That was something I’ve been thinking about,” she says. “A lot of the language that’s associated with food is phonetically interesting, a lot of hard consonants and longer vowel sounds. I always thought it was a slightly lazy way of working in illustrious description into writing and getting some sort of sensory feeling into writing. And there’s also something voluptuous and eroticised about food writing, so I was also mining for this disgusting quality which is something I’m interested in and I find quite appealing – food that is fundamentally a bit gross and slimy or undercooked. That feeling of abjection and indulgence and leaning into something that is quite unpleasant but still pleasurable.”

Similar to food, writing about bodies, particularly women’s bodies, tends to be voluptuous, eroticised and objectified. “One of the things I was interested in exploring is the two messages we receive, or I definitely received about the female body, the idea of constantly striving for perfection but also the messaging that the female body is inherently abject or a bit gross. How do you consolidate or reckon with those two states and ideas of what the female body should be?”

That question comes together during the supper club scenes. “They were probably the parts I found hardest to write because that kind of teetering energy, where it could topple into something else and reach an insurmountable point, is quite a hard energy to capture,” she explains. “One of the things I was thinking about was the idea of the transgressive novel and those typically tend to be quite masculine novels, like American Psycho, A Clockwork Orange or even Fight Club to a lesser extent. Those were novels I found exciting but retrospectively am quite troubled by them.

“In them, women tend to be the course through which men transgress or reach a greater truth – I was interested to know what that would look like from a female perspective and the idea of women using their own bodies to do that.”