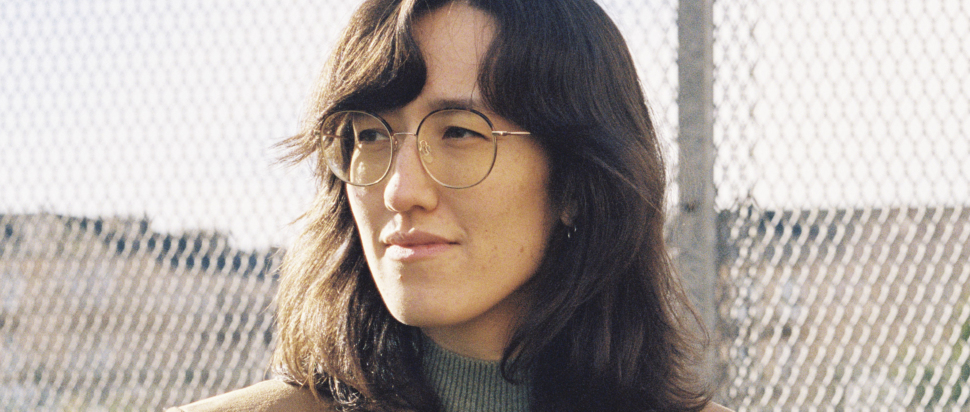

Katie Goh on their new memoir Foreign Fruit

We chat with Edinburgh-based author Katie Goh about their debut memoir Foreign Fruit, and why the symbol of the orange is a potent metaphor for talking about identity

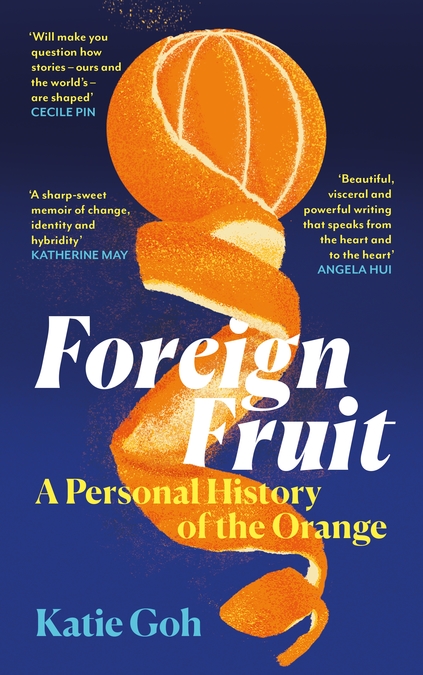

When reflecting upon issues like globalisation, colonialism, and migration, as well as personal concerns such as familial lineages and racial identity, citrus might not be the first thing in most people’s minds. But as Katie Goh proves in their new memoir, Foreign Fruit, the roots and branches of humanity are more entangled with the history of the orange than one might readily assume.

In the prologue of the book they write: “The morning after a white man murdered six Asian women, I ate five oranges.” This moment prompted the introspective and literal journey which would later sprout their memoir. The eating of fruit as an emotionally significant response to violence first became the opening image of Goh’s essay Oranges in Extra Teeth Issue 4, in which they reflect on new ways of writing about identity. The idea would take root, grow too large to be contained in a single essay, and eventually become Foreign Fruit.

When asked to tell us more about the origin and the writing process behind this project, Goh explains: “I have been a journalist for a long time. I got into journalism by doing a lot of personal writing about myself and my identity. People really wanted opinion pieces on what it’s like to be a mixed race woman, a queer woman... This sort of writing feels like packaging your identity up in neat parcels, and I was getting really burnt out doing this. It got to the point, during lockdown, when there was a lot of anti-Asian violence and [I was] being bombarded by that in the news, and I feel like I just broke. I thought ‘I'm not doing that anymore’, and decided to find a different way of writing about my identity.”

What they found was sitting right in front of them: a literal bowl of oranges on the table. Soon it seemed to be everywhere else too, from plastic bottles of juice concentrate in modern fridges to open-air markets along ancient Silk Roads, as well as other, more unexpected places. The research Goh began conducting for their original essay proved the orange to be so ubiquitous in history that the citrus became the central motif of their book. “I started reading about these different significant moments in time, and the orange just kept popping up,” they say. “For example, in [Foreign Fruit] I write about this awful massacre that happened in LA in the 1800s, where many members of the Chinese community were attacked by white citizens. I was reading a book about the tragedy and found something I didn’t know before: that when these people were hiding from the mob, they hid in the orange groves around LA.”

Goh makes it clear that citrus fruit is not only seemingly omnipresent, but its impact can hardly be overstated – the world would look very different without it. “The sailors who were travelling from Europe to colonise lands might not have been able to do that without citrus,” Goh explains as another example of the unexpected ways in which fruit played a fundamental role in history. “They would get scurvy from lack of vitamin C and die, or be forced to go home. Something like an orange or a lemon is the reason why the world is shaped the way it is.”

Looking into the history of the fruit itself also offered many insights, its significance and connection to the author’s life becoming increasingly apparent. “The orange is a hybrid fruit that has two different parent plants [a product of botanical grafting], and its meaning and symbolism has changed as it moved across the world in different times,” Goh explains. “It's both a real fruit that has had a real impact in the world, and also a symbol that has had all these meanings and metaphors bestowed on it.”

This duality became a fertile ground for the author’s vision. “For me, the orange became a metaphor for mixedness and hybridity,” they elaborate. “It comes from China, but it’s moved across the world in a way that follows my own family history: moving from Asia over to Europe. I kept reading about it and realised that it could be a neat entry point to write about big issues I had been trying to grapple with for a long time. So I let the orange guide where I wanted to take the story. It became a really useful way of structuring the messiness of writing about what it feels like to be a person in the world right now.”

More than just a memoir (and Goh’s success at finding an innovative way of writing about their personal history and identity), Foreign Fruit is an impressively well-researched document chronicling centuries of human (and plant) migration, exploitation, violence and ultimately perseverance. “If I’m writing about myself, I need to write about the world as well,” Goh explains. “I don't think there's a rigid boundary between me and other people, or history and the future. I am Irish, Chinese, my family migrated from China to Malaysia at a time when it was under British occupation. I feel like there is so much history in a lot of parts of my identity, and if I was wanting to write about myself, and especially about my family and my heritage, I had to write about things like colonialism and migration. We are all creatures of our circumstances, so if I didn’t write about the wider history around it, then it wouldn’t be authentic.”

Of course, such a task can be incredibly daunting. “I was unsure when I started writing,” they confess. “[I had] a lot of anxiety around it, thinking ‘why am I writing about this?’ ‘Am I the right person to do it?’ I had to let go of the idea of having a completely neutral or balanced way of looking at history. Instead, [this book] is my experience of it, my perspective.”

The construction of a personal narrative and myth-making in general are important themes in Foreign Fruit. “Humans are storytelling creatures. It makes sense that we would turn our past into stories, and then pass [those stories] on to different generations. It creates a sense of belonging, but I think it also has the potential to be very dangerous if you don't let other perspectives or any other myths into that narrative,” Goh says. “For example, growing up in the North of Ireland, being educated in the British system, we weren't taught in school about slavery or colonialism. Many people think of the British Empire as a uniquely positive thing, completely ignoring all the death and suffering it caused. Mythologising history can be very reductionist.”

Similarly, personal myth-making is rarely straightforward. “When I was a kid I would really romanticise China,” Goh recalls. “I felt like I didn't belong to the place where I was growing up and thought that if I could just go to China, everything would be fine. I did have the privilege to go when I was a teenager – as I write about in the book – and it was not that romantic vision I had. I loved meeting my family and seeing the places of the stories I’d heard, but there was no sense of a great homecoming. It was just people living and they didn't really know me. I think it was a very important thing for me to experience because I realised I can't just go somewhere and feel like I found my people or found myself. We create these narratives to give ourselves some comfort, but identities are not static, they are living things.”

The metaphor then goes full circle. As Goh observes: “The orange as we know it has been cultivated over many, many years, to taste perfect, to look perfect, and to appeal to our senses. History has created the fruit the way history creates people.” Sometimes through natural programming, other times as the result of violent dynamics, both human and fruit are constantly transformed by their environment, and in turn transform each other. About the way Foreign Fruit explores this entangled web of connections, Goh adds: “I wanted to dissolve the border between nature and humans, to write about feeling the weight of history propelling all of us forward, and everything that had happened in history dictating what the future will grow into.”

Foreign Fruit is out now with Canongate