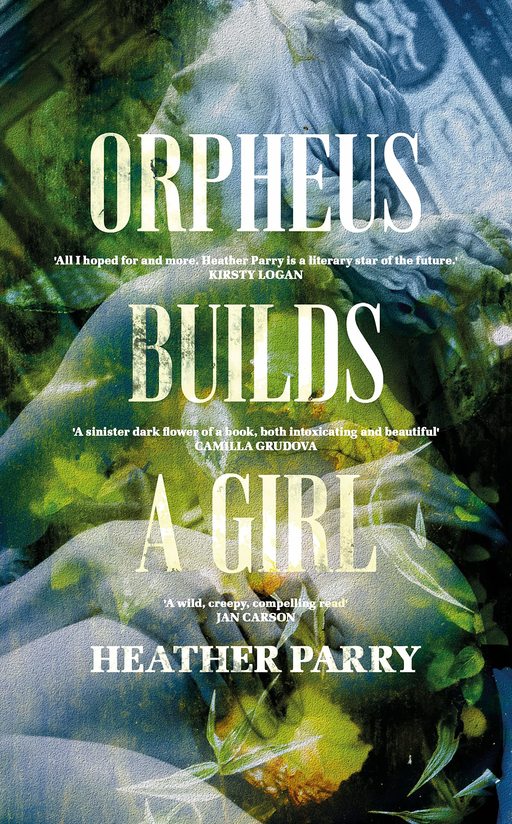

Heather Parry on Orpheus Builds a Girl

Glasgow-based writer and editor Heather Parry introduces Orpheus Builds a Girl, her hotly-anticipated debut, a chilling story of deranged infatuation, medical abuse, coercion and power

Swallowing the reader into the disturbed world of Wilhelm von Tore, Orpheus Builds a Girl chronicles his experiments in post-mortem preservation culminating in a final act of devotion to his young patient, Luciana, while her family are left powerless.

While Heather Parry drew from several historic instances of graverobbing and illicit mummification of women, she first stumbled across the primary inspiration for the plot in a segment of This American Life, on a criminal case from 1950’s Florida. She tells me how the show presented the story as an oddity, a spooky tale, but as ultimately underpinned by love. “I vehemently disagreed with that, I don’t believe that’s what love is at all,” she says, “so I got to thinking, what is it about women’s bodies that socialises the men around them to desire to own them, to literally possess their corpse as an inanimate object?”

Spanning the stories of both a Nazi scientist concealing his identity with forged Polish documents, and Luciana’s Cuban family fleeing revolution, the novel takes place against a backdrop of the characters’ differing experiences as foreigners in 1950’s Florida. “What underpins the book is the idea of the American dream,” Parry notes. “We’re told that it’s this land of opportunity, but that’s clearly not distributed equally, [...] I wanted to ask where the privilege lies; if people don’t get rich, can they get away with things? Maybe they are able to build a stable home, but at what cost?”

The plot, which unrelentingly drags its limp reader towards its inevitable yet nonetheless horrifying conclusion, is partially told from von Tore’s perspective, echoing the work of Nabokov and Yanagihara by forcing the reader to peer through the perpetrator’s eyes. You’re smothered by the cloying affections of a madman while the voice of Gabriela, Luciana’s mournful sister, gives you hope for a justice that never comes. “I wanted there to be a voice in opposition to his, not just so that you had to think about what he’d done,” explains Parry on interweaving the two perspectives, “but so you’d think about the way society excused it, something that plays out time and time again.”

When I was preparing for this interview, there was a nine-hour queue snaking around central Edinburgh, as people lined up to view the casket of the late Queen Elizabeth. I was struck by the parallels between this national display of mourning, and the public spectacle made of poor Luciana’s body in the novel. I mention this to Parry. “God, what a time to bring out a book about the bizarre, fucked up and nonsensical things that can happen to a woman's body after she dies!” she laughs. “In a way, they couldn’t be more different – we’ve got the entire state apparatus protecting one person's body, and the exact opposite happens to Luciana.”

When asked how the process of writing the book had made her think about the social mechanisms of death, she speaks about her research on different cultural death rituals, citing the work of Caitlin Doughty and Carla Valentine. “It’s also fascinating the way we treat people towards the end of their lives, what agency we give people over their own deaths – none, in this country,” she reflects. “It makes you think about your own death; how much of the process of you dying is for you, and how much of it is for other people.

“My mum once said to me; ‘Heather, why don’t you write anything nice?’” she laughs, as I ask her about the sinister themes that permeate her work. “I love the way gothic literature talks about the body,” she enthuses. “How it talks about social change, about what’s pushed to the edges, who's considered an outsider and why.” When she comes across stories of extreme injustice, the twisted side of humanity which challenges her generally optimistic worldview, she writes to unpick her own reactions – to look directly at the darkness in order to understand it.

Our conversation draws to a close as we marvel over the grotesque, visceral aspects of having a body and leaving it behind; from the surprisingly yellow hue of fat beneath skin to all the post-mortem minutiae that she vividly describes in the book. It’s clear that Parry’s writing, for both herself and her reader, serves to fight against the human urge to turn away from the grotesque, to flinch when faced with things that disturb us. “The weekend after the book comes out, I’m going to see a live autopsy!” she tells me cheerfully – and I, for one, hope that it gives her the answers she’s looking for.

Orpheus Builds a Girl is out on 6 Oct via Belgravia Books