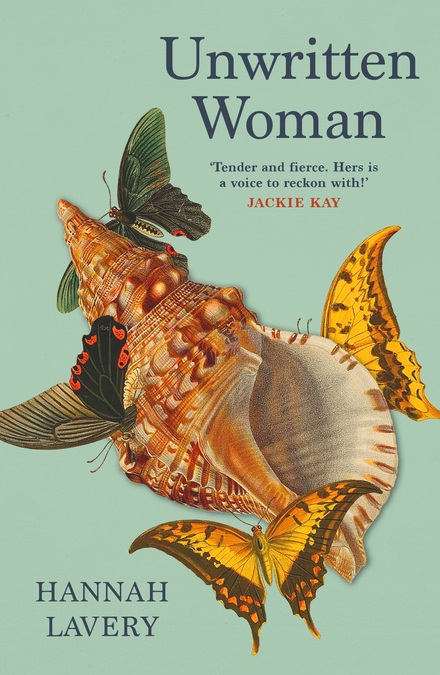

Hannah Lavery on her new collection Unwritten Woman

We chat with Edinburgh Makar Hannah Lavery about her new collection Unwritten Woman, the power of retelling, and the ongoing influence of Edinburgh in her writing

“It felt right to be singular in that way, I suppose,” says Hannah Lavery, commenting on the title of her new collection Unwritten Woman. Distinctly less autobiographical than her debut collection Blood Salt Spring, a plethora of voices come together – chorus-like and rousing. “It feels like I’m pushing out of myself and into other personas... But I don’t want to say that I’m speaking for all of the unwritten women because that would be ridiculous.”

Following on from her debut collection published in 2022, Edinburgh’s Makar returns with Unwritten Woman, a fiercely tender exploration of women in the margins. A study in duality, the collection is split into two halves: the first gives a voice to the women of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the second explores Lavery’s experiences as a woman of colour in Scotland, particularly looking towards her relationship with institutions at large. Amid a continuous call and response, Edinburgh as a city is told and retold from the perspective of a mixed race woman. Dualities strike and carve and fold themselves within the collection; Lavery allows them this and plays with it, delighting in the oppositions.

Back in spring 2021, Lavery wrote a retelling of the Jekyll and Hyde tale from the perspective of the women characters for Pitlochry Festival Theatre; upon finishing the play, she realised she wasn’t quite finished exploring their stories. Although the novella is hailed as an exploration of the human condition, presenting humanity in all its filthy complexities, it largely excludes women, their characters barely heard from the margins of the text.

“As a woman and as a woman of colour, we’re given these canonical texts – usually by white men – and we’re told to find a way of connecting and how to understand them. So we spend a lot of time reading work where we’re not centred,” says Lavery. In retelling, however, there’s a radical potential to not only re-centre and understand oneself but also to engender new possibilities for the text in its entirety. For Lavery, reading Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea was a revelation; Jane Eyre never quite resonated because, for Lavery, she was the Woman in the Attic, not Jane. With Unwritten Woman, Lavery sought a similar solace. “I find myself in the edges, these silences and absences, so I just wanted to write those back in. I think it's almost an experiment in being a reader. 'How do I meet this text? How do I read this text?'”

Despite this silencing, women’s roles in Jekyll and Hyde are crucial to any understanding of humanity within the novella. “When men are revealed as being monsters, there's always a woman or a group of women that have gone, ‘We've been telling you this,’ or, ‘We knew that so it's no surprise to us.’” In this, Unwritten Woman gives breath to unsung knowings – those of women, those of people of colour. Such knowing is not the stuff of Edinburgh’s Enlightenment; rather, it’s a shared instinct, relentlessly tugged outwards through the very experiences of existing as a marginalised person.

“I’m generalising but for women, our duality is actually around our anxiety. It's around our fear. It's the fact that we present a certain way in our world, but we actually have to hold a lot of our own fear, a lot of our anxiety,” says Lavery. Growing up, young girls are fed dangers as both fact and fairytale. Such is carried with us into womanhood, but always hidden and unspoken. Although Jekyll and Hyde is set in London, it’s a novella ever bound to and associated with Edinburgh; in both parts of the collection, Lavery situates these anxieties carried by women in this city and its dark history.

Coming to the end of her time as Edinburgh Makar, Lavery was keen to look at the city she calls home and its poetics. “We have a certain veneer of respectability, or we have this politeness that we have to serve but underneath there’s this whole other thing,” she laughs. The Edinburgh neatly packed and parcelled for an international audience – private schools, cobbled streets, shortbread tins – is not all that honest. As Lavery notes, “we hold up the Enlightenment and yet so much of the Enlightenment is what led to so much underpinning of racism and colonialism.” In Unwritten Woman, Lavery calls to home-truths outwith the visitors’ centre. It’s a little filthy, certainly uncomfortable; but it’s also full of its own warmth, and a joy like no other.

As in Blood Salt Spring, the haar – the city’s somewhat beloved coastal fog – draws Lavery in once again. “I grew up in Edinburgh, in Portobello, so I was always under the haar. The haar is a very physical thing,” says Lavery. In mid-air, her hands roll, slowly, around each other; the haar coming in and out. In gesture and in poetry, she writes it anew. “It's about being separate within a space and the way that envelops you but also the way in which it smothers you and holds you under so there's a sense of being under something.” The very ecosystem of the city becomes a metaphor for the experiences of people of colour within it; that is, a city with a past (and present) of contributing to and utilising their oppression.

Ever hopeful, the collection offers a different map – a less white map – by which to navigate Scotland’s culture. In the second part, we begin with Jackie Kay; end with Young Fathers; find Alberta Whittle along the way. Cultural touchstones are placed and replaced, and it’s something to celebrate. “I wanted to be in conversation with other artists,” Lavery says. Rejecting an artistic individualism, she is keen to present her creativity in community with that of others; here, solidarity is tangible and demands our witness. “When people of colour speak in Scotland, it's for a moment. It feels like it's a shining moment and then it slowly gets enveloped and gets lost.” And so, Lavery writes them into permanence in this collection, remembering them in the present tense and refusing a future loss.

Speaking to contemporary working lives, Lavery explores the difficulties put upon this community. In the second part of the collection, a number of Theatre Announcements act as a drum beat, inserting themselves between every poem. Cutting and inciting, the announcements echo the everyday racist rhetoric endured by people of colour in Scotland’s creative scenes.

“I’m calling them Theatre Announcements but, in a sense, they’re Institutional Announcements,” says Lavery. Thinly veiled with anti-racist-training lip service, prejudice seeps through – subtly and then all at once, and certainly laughably so. “When you're an artist of colour, when you work with institutions, it's those little moments... Those little interjections felt to me very much like the way in which I speak with other people of colour. It's that exhaustion, but also the humour and the rage of it.”

Humour sits nicely in Unwritten Woman (particularly for readers with certain marginalised experiences). “I was having a lot of fun and mostly it was just the way the poems came out – they were asking to come out that way and to be looked at that way. I hadn’t set out to be experimental,” she explains. Somewhat a stylistic departure from Blood Salt Spring, Unwritten Woman was edited by Joelle Taylor and Lavery is thankful for these interventions, encouraging her to have confidence in her poetic instincts. Working with Taylor allowed her to “push the poem as far as it could go,” a sentiment which is palpable on each and every page.

With Unwritten Woman, we’re unafraid of our own rage. Lavery doesn’t offer hollow whitewashed feminism; rather, she pulls at an intersectional feminism, studying how it looks, feels, moves. It’s a calling to take another look, re-read that line, and question where the women are – especially those of colour – and how we may hear their stories. As if Lavery’s talents needed any further preaching, Unwritten Woman hails her as a triumph.

Unwritten Woman is out now with Birlinn

Hannah Lavery will be appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival alongside Salena Godden on 11 Aug at 5pm