Say No! Art, Activism and Feminist Refusal @ Wardlaw Museum, St Andrews

In St Andrews, an exhibition stands firm against exclusionary and oppressive feminisms, defying transphobic and anti-sex work backlash

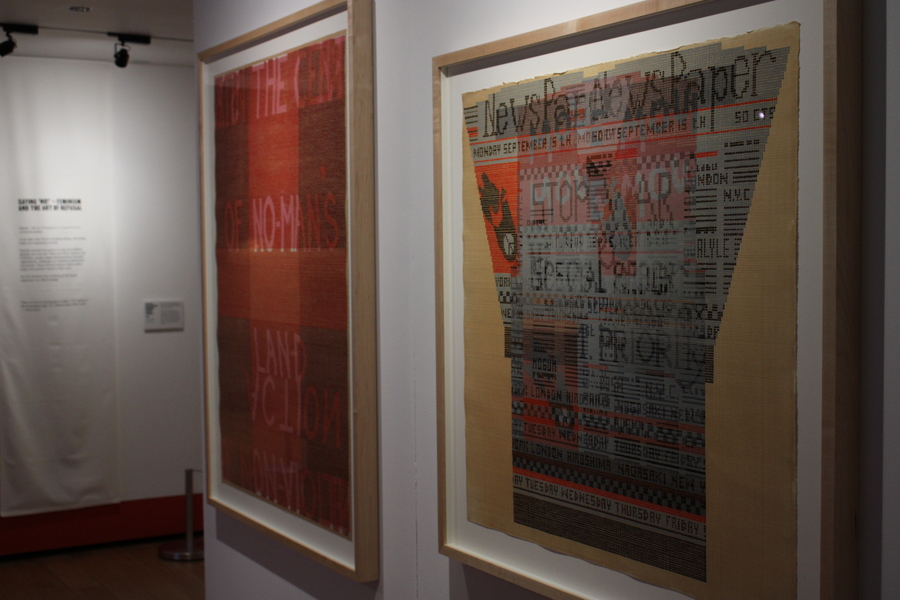

At St Andrew’s Wardlaw Museum, Say No! Art, Activism and Feminist Refusal foregrounds art as a protest tool. It’s an exhibition that mobilises you into action. Co-curated by Camila Cavalcante, Lexington Davis, Laura Brown and Eilidh Lawrence, the concept behind it draws on a wealth of feminist theories of refusal by scholars such as Audra Simpson, Saidiya Hartman and Tina Campt. But you don’t need to be scholarly to engage; we can all think of a time that we opted to not challenge the status quo for the sake of comfort or safety.

The artworks are grouped broadly into stories of resistance against exploitation, violence, and limits. Some artists directly engage with political struggle; others are poetic in their defiance. Franki Raffles’ Zero Tolerance Posters make an unequivocal statement: violence against women is never acceptable. Alberta Whittle’s film A Black Footprint is a Beautiful Thing advocates for the shipworm – a tiny marine creature that, by eating away at wooden vessels, disrupted the Atlantic slave trade. In their own ways, each artist underscores the power of refusal as a necessity.

Ever since visiting Say No! I’ve been keeping a log of all the times I said yes, when I should’ve said no.

Here are my most recent entries in my notes app:

• I nodded when my driving instructor slipped into conversation that women are inherently untrustworthy (In my defence, it was my first time on a dual carriageway).

• “Yes please to that extra piece of freelance work” replies my imposter syndrome on my behalf as I’m terrified that deploying that diabolical phrase “at capacity” is a ticking time bomb to literally never working again.

• Fine, okay, @ the person who told me bisexual women always end up in heterosexual relationships.

This is a chronic case of going along with it. Some moments are silly, others feel seismic, but they reveal an impulse to smooth things rather than engage in dialogue or sit with tension.

Curious, I ask co-curator Lexington Davies if she’s ever said yes when she should’ve said no. Immediately, I feel shy – contradicting everything they teach you about journalism – and squeeze in a caveat: only if you feel comfortable answering. Imagine if she refused a question about feminist refusal?

Unsurprisingly, as an academic in the arts, Lexington also cites overcommitting to work. But then, with trepidation, she shares something far weightier. Lexington opens up about the backlash to the exhibition’s trans-inclusive and pro-sex work ethos.

Overtly confrontational pieces in Say No! use the language of protest to refuse subtlety entirely. Pissed Off Trannies: Zap 1 (2019) captures a radical act of defiance by the activist group Pissed Off Trannies (POT), who lined the entrance of the Equality and Human Rights Commission HQ with sixty bottles of trans people’s urine. It was a direct, visceral response to attempts to exclude trans people from single-sex spaces. POT tramples on the reductive, never-ending debate around public bathrooms; if trans people can’t piss in a cubicle that reflects their gender, they’ll piss on the institutions that deny their existence, their dignity, their autonomy. Nearby, a banner by Scottish sex-worker-led organisation SCOT-PEP, created in collaboration with artists Fiona Jardine and Petra Bauer, commands attention. Vibrant in both colour palette and message, it demands visibility for sex workers’ rights, safety, and health in Scotland. Meanwhile, in the accompanying book club, members of the public are invited to explore the exhibition's themes via Julia Serano's Excluded, Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive, and Revolting Prostitutes by Juno Mac and Molly Smith.

Through the artworks on display and the public programme, the exhibition continues to say no (read: up yours) to the vocal minority peddling trans-exclusionary and anti-sex work propaganda, riled up by a Facebook forum. “There are feminisms,” Lexington says. “And some, to me, are anti-feminist – but they operate under the banner of feminism. An exhibition like this situates itself as supporting a certain type of feminism: trans-feminist and pro-sex workers.” While feminisms may be plural, Lexington’s stance is unwavering: “There’s no space in our framework for opposition to that.”

As Lexington articulates her refusal, I think about Sara Ahmed’s landmark essay ‘Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects)’, where she asks: “Do you go along with it? What does it mean not to go along with it?” Ahmed describes the political struggle of people who refuse to conform to dominant power structures – particularly those whose bodies are culturally marginalised – whose resistance disrupts the social order, causing friction from the family dinner table to public life. If Say No!’s artists and curators can so explicitly, so defiantly reject exclusionary and oppressive feminisms, then this is an exhibition that empowers its visitors to do the same. It urges us to stop nodding along – to live our politics and stand by them.

Say No! Art, Activism and Feminist Refusal at the Wardlaw Museum until 11 May.

st-andrews.ac.uk