Everlyn Nicodemus @ Modern One, Edinburgh

The first-ever retrospective of artworks by Edinburgh-based and Tanzania-born Everlyn Nicodemus is poignant, intimate, potent and bold

Shapes spin inwardly. Broad strokes and bold colours are indulged. Patterns appear expansive and grand; singular colours appear somehow minute and intricate. Whether depicting pain or joy, Everlyn Nicodemus’s genius is in her bold metamorphosis of the body.

Although Nicodemus’s academic work is long renowned, her artistic work has received little recognition until recent years. This impressive retrospective of her work by National Galleries Scotland goes some way to addressing this. With a tender forcefulness, the Edinburgh-based and Tanzania-born artist centres women’s oppression alongside individual and collective trauma.

Lined across a wall of the central corridor, The Object – a series of 24 drawings which depict a depressive period in Nicodemus’s life – begins the exhibition. Charcoal scratches tug us round and round in their melancholy. For a retrospective so buoyed by a colourful vitality, it’s an affecting yet jarring entry point. Elsewhere, placement retains its purposefulness, with instances such as Woman (1983) facing opposite its counterpart Two Black Candles (1983). Duality is spoken to, rather than insisted upon. Indeed, in Nicodemus’s early work, her signature – simply, ‘Everlyn’, no surname – finds itself nestled into a mother’s foot or curved around a blooming flower. Seeking its placement is a small joy. Later, the signature finds itself neatly sat in a bottom corner, left or right. Only a retrospective of this expanse can offer such intimacies at large.

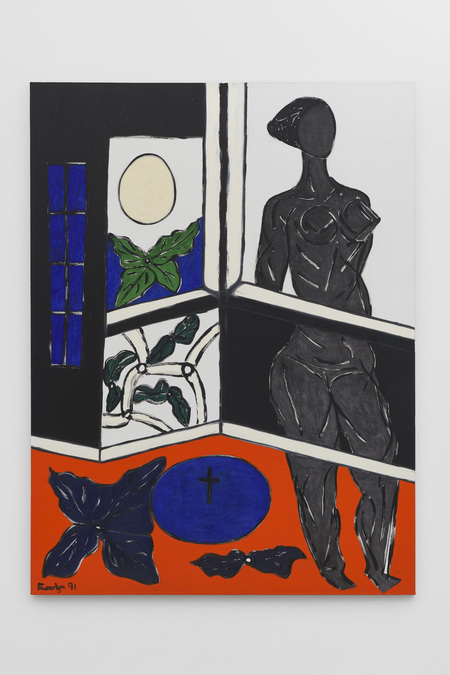

The Wedding 45 by Everlyn Nicodemus, 1991, National Galleries of Scotland. Purchased with help from the Olive Pollock Morris Bequest and the Cecil & Mary Gibson Bequest, with contributions from private donors, 2024. Copyright the Artist

And, certainly, Nicodemus’s work renders human intimacy anew. In a hot red and an even hotter blue, Man and Woman (1983) shows the artist and Kristian Romare, her late husband, embracing and becoming one another; the exhibition is dedicated to him, for his dedication and love over the years. Her later self-portrait series The Wedding (1991-92), consisting of 84 paintings, considers the brink between life and death, following the artist’s near-death experience. Peculiarly beautiful paintings depict her confronting death, speaking to her associated post-traumatic stress disorder, rendered in a quiet black as well as gorgeous purples, blues, yellows, and oranges.

The newly produced series Lazarus Jacaranda heralds the restorative, life-giving potential of art. Departing from Lazarus’s biblical binds, Nicodemus instead depicts female figures in a near luminous, burgeoning orange, with jacaranda flowers resting at each body's base. Coupled with the deep midnight blue of the room’s walls, the series offers no less than an otherworldly state. But this glorious closing is not a closing at all: a small room follows, containing a collection of Nicodemus’s textiles before a corridor of collage-based paper works. The grandeur of Lazarus Jacaranda is somewhat too quickly lost in the timid return to normality.

Everlyn Nicodemus with works from her new series, Lazarus Jacaranda (2022–24), created for the exhibition. Photo: Neil Hanna

Although deeply bound to her inner world, Nicodemus’s work also looks outward, to both the past and the present. Gynaecologist Chair (1983) speaks to women’s lack of agency at the hands of male gynaecologists; overhead lights appear trumpet-like in the same brilliant gold as the woman’s bent legs. Set Free (1985) is based upon the collective will of women across Tanzania – in Arusha, Dar es Salaam and Moshi – to attain financial and cultural freedom from their male counterparts. A singular subject is refused, while the collective focus of women’s oppression and liberation is embraced. On arriving and departing the exhibition, however, it is inevitably difficult to overlook the Baillie Gifford logo and its too-proud support of such beautifully radical works. With the recent knowledge of their unethical investments, their funding of art – whether a single exhibition or an institution at large – is deeply uncomfortable.

Undoubtedly, Nicodemus paints with a wonder that is as poignant as it is potent. Despite some structural limitations, her retrospective welcomes us and holds us. We are indebted to her for this.

Everlyn Nicodemus, National Galleries Scotland: Modern One, Edinburgh, until 25 May, free

nationalgalleries.org/exhibition/everlyn-nicodemus