Duncan of Jordanstone Degree Show 2023: The review

This year's DJCAD graduates overcame the setbacks of the pandemic to create a range of dynamic and stimulating works

The Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design degree show opened in typical Scottish springtime fashion: beneath a hot, humid curtain of drizzle. Despite the weather, the show was busy; a sight that would have been unthinkable three years ago. While COVID-19 certainly defined this cohort’s university experience, it doesn’t seem to have dampened the force and breadth of the work on display. It was evident that across every department, students have been interrogating contemporary issues and addressing the role that artists play in navigating them.

The Anthropocene was a big theme across the school. From Art and Philosophy, Eve McGovern Miller’s moving multidisciplinary work captures the ‘strained’ relationships between humans and the ecologies they attempt to control. In one corner, a video shows a large ball of wool created by Miller, rolling endlessly downhill. The playful sentience of the ball (is it trying to escape us? Or does it represent us and our Sisyphean efforts to dominate nature?) complements a large sprawling spider diagram which simply, yet effectively, charts interspecies entanglement. Coursing down a plinth are Anna Lamb’s elegant knitted wall-hangings which visually combine the neatness of a distant landscape with the subtle, close-up messiness of soil horizons. Drawing on her Scottish heritage, Lamb’s use of mainly Scottish spun wool references the history of the nation’s textile industry with a distinctly contemporary nod to abstraction, as if the Bauhaus were in fact located in Portsoy.

Work by Anna Lamb from the DJCAD Degree Show.

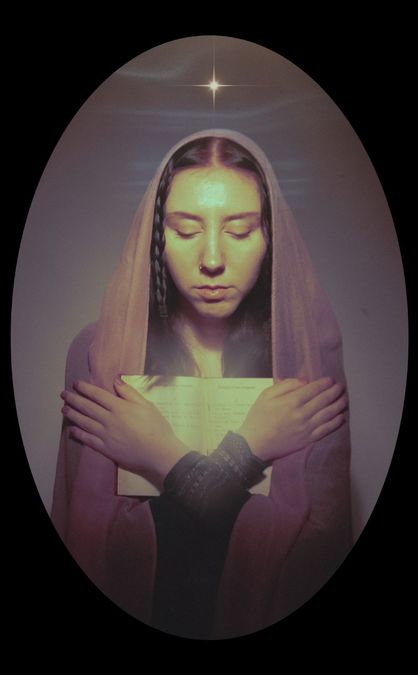

In Interior and Environmental Design, Eve Willis Kelly’s ‘design for the future’ project seamlessly interweaves the modern and the medieval in the ‘Isle of Alucinari’; a holistic psilocybin-inspired medicinal retreat located on the Island of Lindisfarne. With a nod to the theories about the psychedelic roots of Christianity, Kelly recreates the anatomy of fungi in a design that is both tender and palpably calm. Religion also features in the work of Lily Smith, whose functionless chalices are among the stand-out pieces in the show. Intended to symbolise their own fraught relationship with the Church, Smith’s flawless metalwork, which evokes the modest perfectionism of Shaker design, matches (and maybe even surpasses) its Catholic reference point. Traditional depictions of feminine divinity are reimagined in Maria Touloupa’s dreamy holographic portraits, reframing saintly female beauty in a fantasised, post-human world of AI.

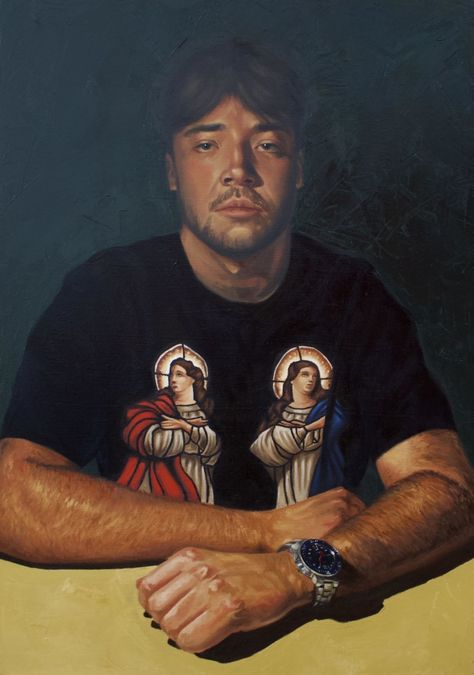

Elsewhere in Fine Art, figuration dominates. Kristin Mackinnon’s masterful, larger-than-life A Painter Worth Taking Seriously addresses the gender imbalance in the art world in a humorous take on self-portraiture. Perspective is also key to Nina Kouklaki’s slick, stylish oils. In the series, which explores the world of fetish, a svelte, nude figure contorts erotically with a plastic flamingo and a rubber balloon. Spectacle features in Oliver Campbell’s fuzzy, almost pixelated paintings which recount iconic cultural scenes, such as Messi’s 2022 World Cup win, with Baroque pathos.

Generally, participatory art is hard to nail as it relies on controlling a notoriously tricky factor; the public. However, Ailith Stewart's interactive installation, reminiscent of a prehistoric cave, succeeds brilliantly by inviting the public to make marks on the piece in an act of vandalism, boldly questioning the value we, as a society, place on certain forms of art. A truly noble message, affirmed by the audience responses which prove that nothing reminds us quite of our shared cultural sensibility like a cock and balls scrawled on a cave wall.

Work by Kirstin Mackinnon at the DJCAD Degree Show.

COVID-19 has certainly changed our relationship to public space, and it is inspiring to see artists tackle something so pedestrian and often overlooked. To explore the concept of ‘common ground’, Clyde Williamson, in his video piece Getting Through, squeezes through a broken railing, behind a bike in a stairwell and under a bin. This playful negotiation with ‘urban obstacles’ hints at a deeper question of design vs. serendipity in urban environments (are these spaces designed to be hostile?), as well as the bodies those spaces sanction or exclude. Someone whose work to watch, or they’ll slink away under a Biffa bin forever.

Despite the galvanising variety of work, navigating through the building was tricky. Compounded by the absence of invigilators, there was, among visitors, a general sense of mass confusion. Even with the readily available map, it was genuinely surprising to find a room containing art – a real problem for a school in the top percent of art schools in the country. Due to the labyrinthine nature of the building, it appeared easy for artists to get overlooked – especially those further away from lifts or fire exits. Perhaps a note to future curators of the show is to consider access at the forefront of their planning. That aside, Dundee’s graduates demonstrated that honest, self-assertive and fascinating quality that has historically defined the school, and hopefully will continue to define it.