Artist Basma Alsharif Reimagines the Middle East

Artist Basma alSharif's new exhibition in CCA centres on a novella that is in parts sci-fi fantasy, historical fiction and erotica. Titled A Philistine, it undoes political borders in the Middle East, and reimagines possible pasts and futures

The Skinny: What can we expect from your upcoming show at CCA?

Basma alSharif: I had been thinking for a long time that I really wanted to do a work centred around a text that I wrote, and that the exhibition itself would be a reading space for this book essentially. Whenever I say book, I feel a little uncomfortable because it's not something I would publish officially but something that really is an artwork that exists in a gallery, that doesn’t leave.

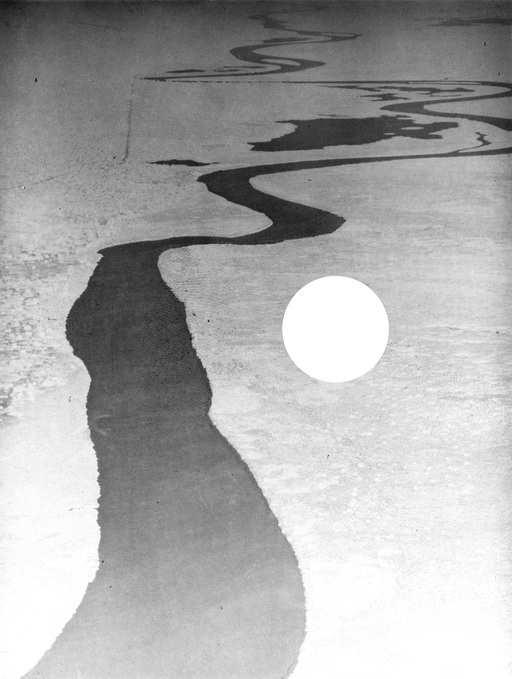

I decided to make a text about a fictional journey. It goes along trainlines that used to exist in the Middle East, that became discontinued when Palestine was occupied. So I reconstructed those trainlines – there are certain connections that never existed, some which were actually train stops. The story moves backwards in time, so it starts in the present day Lebanon, to Palestine in 1935 and winds up in Egypt’s Late Dynasty, roughly 1150 BC.

The book itself is filled with a lot of allegories that we find ourselves in today like how heavily present borders are which didn’t used to exist. It does some work to undo them, to undo these physical borders. It also brings up sociopolitical issues that are present – what if that hadn’t happened, what if the Middle East hadn’t been colonised? What if Palestine was never occupied?

So, inherently through this fictional story I was wanting to deal with things becoming obsolete that we imagine are irreversible. For me that tied into making this book and having it be a physical object, something that’s not digital, that can’t be shared. Something that you really have to hold and read, because I also feel a separate agenda of the work is that I feel like the act of reading a book is becoming antiquated practice.

The text is written in English and Arabic. It is a vernacular Arabic, so it’s not an official written language but the way that people speak, because there’s a very big split between the way people speak and how people write Arabic. There is classical Arabic which is very formal, then there is the colloquial vernacular Arabic which differs region to region. It is written in a Palestinian vernacular and we are going to have a voiceover of someone reading an excerpt from the book.

Your use of science fiction and erotica styles is particularly intriguing, what artistic freedoms did that allow you?

I wanted it to be kept in three different genres. One was history, one was science fiction and fantasy, and the last, erotica. Having this leniency to imagine things in these landscapes that didn’t exist and to portray the history of what actually happened.

[I] force the reader to imagine something other than what is present or past and also to push the language. Especially with the erotica section, [I] insist that the text needed to be written in a vernacular language because classical Arabic doesn’t have a lot of erotic terms. There are a lot of people who just don’t believe that vernacular Arabic should ever be written, that the only form of Arabic is classical Arabic.

You talked about using archival footage – how much do you use archives and what is your experience of approaching these places as an artist?

I have used archives a lot. It is often a mix with my own work. Especially when it is regarding colonial [photographs] that were taken in Palestine by foreigners or colonisers essentially. I feel like there is something [of interest] about bluntly reappropriating these images and getting to decide how they function, regardless of whether or not it is right or legal. Because to me what happened previously is neither right or legal. We can’t maybe outwardly call it a political act but an insistence by using many of these images that are not mine to varying degrees of copyright infringement.

Have you had much resistance to your work or perhaps incessant questioning? What is the emotional labour of having to explain yourself like?

There hasn’t been much resistance. But I think what does happen quite often, and I think maybe more and more now when spaces are trying to be more inclusive of non-Western artists, is that in seeing my work, you become a representative. Your work becomes a statement of the entire region, which I find really absurd and frankly really problematic. It's surprising also because I grew up in the West. I speak English and I was educated in the United States, and I feel like a lot of my references are unfortunately primarily coming from Western culture. So it’s very strange to have my work be contextualised and be [representative of] a kind of Middle Eastern perspective, which it is trying not to do.

If anything I am trying to make my work perspective-less, a multi-perspective. [I'm] taking into account different cultural contexts and languages and not speaking to or from anything in particular. Although obviously a lot of it is my connection and background to Palestine. But I often feel like it gets boiled down to “you’re an Arab artist, you’re a Palestinian artist, you're speaking on behalf of something.”

What is the art scene is like in Cairo? Is that where you're based right now?

As far as my experience anyway from 10-15 years ago to now, I feel like there are more spaces for contemporary art and film, and there’s definitely more artists, but at the same time it’s a very difficult place to organise things.

It's difficult to organise even a public opening, because there are no protest laws. So any kind of gathering is forbidden and art space funding is difficult. It wasn’t an easy decision to come and live here. Sometimes I question it. But I think these things exist in one way or another, and here you are really confronted with it and there’s something to not being able to ignore the reality of how fucked up the state is. It is really important and makes you think about how are you going to make a piece and exist as a person and how do you create a community?

It is not worth sugar-coating the fact that it is difficult but the very fact that people want to put on shows or have screenings is really meaningful. It feels really good to be close to that and it is important to be present here when a lot of people are trying to leave. They have given up for good reason. But if you have the privilege of having a passport that allows you to leave whenever you can it’s actually worth trying to be here and engaging with whatever cultural scene is present.

A Philistine, Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, until 15 Dec