Stories Told On Silk: Emma Talbot on her DCA exhibition

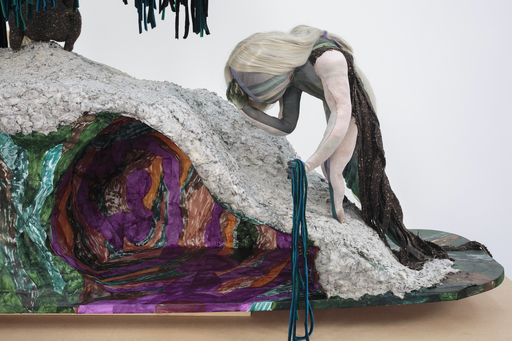

Emma Talbot's upcoming exhibition at DCA sees her create exploded narratives around grief of 'failing systems' in the current 'point of crash', all within a deftly made, immersive installation of paintings, sculpture and film

Emma Talbot begins describing her latest exhibition in Dundee Contemporary Arts with the story of how she came into contact with The Riders of the Sidhe, John Duncan’s Celtic Revival painting at the McManus Museum. “Almost in a cursory way, the Head of Exhibitions showing me around, said, 'You won’t be that interested in that.' And I thought, 'Oh God, I really am.' It’s this really elaborate image, and it incorporates these archaeological finds that are actually in museums in Scotland. They’re put into this narrative painting as if the painter is imagining them being used in real life by these ancient mythological figures, like fairies and knights.” It’s fitting for Talbot to start with an anecdote, as storytelling is something she plays with and pulls apart across her evocative, deftly made installations of paintings, drawings, sound, animations and sculpture.

This historical painting of an imagined, forgotten time brought Talbot to one way of rethinking the relationship of landscape and material, social and cultural histories. “I thought it was so interesting to imagine that there are elements from previous cultures that are buried in the landscape. We’re present, but we’re not really aware of them. We don’t really know what those cultures were, and our own culture might become like that. People might not know how we lived. What we did, what we saw. My work is so much about what it’s like to be alive today, what we think, what I think, what it’s like to be a human being in the world today. So it seemed like a way of thinking about certain landscapes in Scotland, as containers of all these histories.”

Thinking of the inevitable losses that happen between different historical moments, Talbot considers these ideas as especially relevant during the many epochal shifts that are underway. “I was thinking about what our lives are like now… We can see how things are changing in front of our eyes. Systems are failing, and I thought if we come out of this point of crash, we’ll wonder how to live, but we’ll also grieve for how we used to live, how things used to be and people that we’ve lost.”

Moving between the ancient and the contemporary, it’s at this point in her thinking that Talbot returned to a Celtic tradition of caoineadh, meaning 'crying', also referred to as 'keening'. Artist-research group The Keening Wake describes the practice as “a vocal ritual artform, performed at the wake or graveside in mourning of the dead. Keens are said to have contained raw unearthly emotion, spontaneous word, repeated motifs, crying and elements of song.”

For Ghost Calls, this gave Talbot the “idea that there could be a group of women who are like Celtic keeners, professional mourners... [who] would transform the soul from the living, from earth, to the next world, by doing this. They help the family access their grieving emotions, and I thought wouldn’t it be great if there were a group of women who were like guides who were guiding us now, through this crash and through our grief?” She imagines the women showing the way into an interior landscape of grief, the terrain of which, for Talbot, can be imagined as looking like the Scottish landscape. These keeners could “help us move from one place to another – from now to the future.”

While this gives some sense of one of the thematics of Ghost Calls, Talbot is clear that any narrative in the new work remains “open ended”. She sets up a constellation of references, that can allow for lots of openings for different ideas to enter. “Like what you might meet in a landscape, and what keening might sound like.” Speaking about this conceptual and visual layering, Talbot describes it as an analogue of human experience, creating installations “that operate like the thoughts in a head and the layers of sensitivity that make up that experience. Sometimes thoughts are precise – words, images, motifs – clear ideas and sometimes they are more evocative, atmospheric, sensory – with pattern, colour, sound in the work, a kind of atmosphere is created that then contains or sits with a whole load of thoughts around a subject.”

This sense of psychological interiority comes out visually in the unique and personal anatomy that Talbot has developed in the deceptively innocent-seeming, big-headed figures that populate many of her drawings and paintings. “They started out from the idea of being in a body looking from inside out, so feeling what it’s like to be in my body. So at first I exaggerated my own physicality – wider shoulders and slimmer hips and the hair is a reference to my hair – but the heads were larger because quite often I wanted to be able to draw something inside the head (like a thought), and the figures often have multiple limbs because they’re doing multiple things or making different gestures. They’re kind of projections of thinking rather than concerns about what things look like in the external world.” The result: an uncanny sense of rapport with the idiosyncratic representations of the human form that feature in the works.

As well as creating an alternative system of anatomy, Talbot’s choice of silk as the substrate for many of her paintings deliberately pushes against the usual habits and expectations of the medium. She “didn’t like the format of rectangular, rigid, stretched canvas. They seemed to belong to a tradition and history of paintings that was already so heavy and prescribed.” Silk presented itself as “a surface that I could paint on like paper, but that could be cut, sewn, shaped and draped.” Talbot describes it as “incredibly resilient and strong even though it’s very light.” It also presents new ways of interacting with the images she creates, as they can be seen from both sides. “And once I’d figured out the best way to paint on it, it demands that you are very immediate, you can’t change the marks you’ve made – so it felt very free.”

Away from disciplinary strictures or the classical expectations of the many different media she works with, Talbot’s working methods can be responsive and robust enough to contain and confront myriad subject matters. She also candidly describes the ways that her changing situation in life, particularly her role as a mother as her children become adults, have informed the different transformations of her practice.

“As time has gone on, the figures have more freedom (as I do, my sons have grown up) and they really travel about in universal space, in broader contexts – so [the work] has become differently existential and it also addresses prevalent contemporary concerns… I’m always aware of being alive now and life’s brevity as well as our interconnectedness with a much longer timespan.

"It’s like micro and macro thinking, terribly intimate and widely universal. I’m also really interested in a kind of mystery. Life is a mystery, nature is a mystery, there’s magic contained, meaning contained that is exciting. I feel very motivated to think in terms of ancient and futuristic, but I think that’s a theme of our times, the zeitgeist of our times.”

Between the ways Talbot describes figures, the expansiveness of her exploded narratives, and the idiosyncrasy of her material choices, her practice seems to have rich parallels in painting, comics, textiles, as well as experimental sound and animation, while still evading any of these categories. The interview rounds off with asking how important it is for her that her practice takes this markedly singular form. “I had to make a practice that was tailored to me, to what I’m interested in, what I like to look at, how I think. I only do what I really want to do, otherwise there’s no feeling in it. It looks just how I want it to look, it says what I really think, it sounds like something that I find exciting. That way, even if no one else was interested, it wouldn’t matter. I would still love making the work.”

Emma Talbot: Ghost Calls will open at Dundee Contemporary Arts once COVID restrictions allow; follow DCA on social media for updates

Photos by Ruth Clark