Movement and Material: In conversation with Delaine Le Bas

We speak to Delaine Le Bas, Turner Prize 2024 nominee, about her new exhibition, Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding

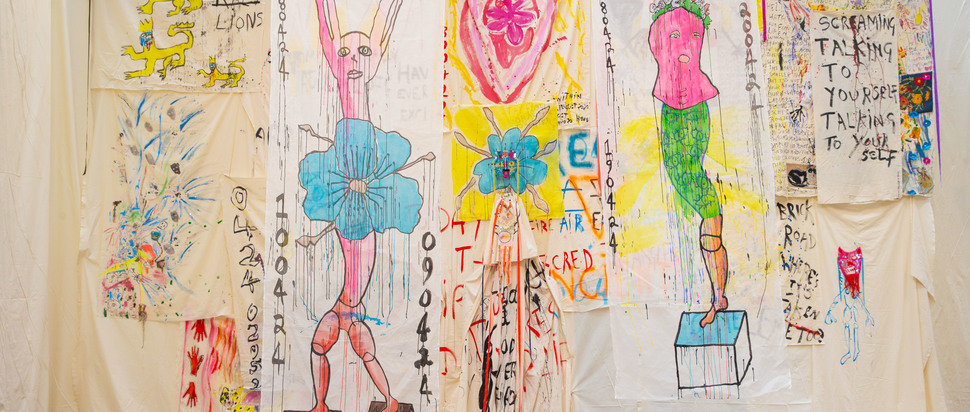

“Fear is used to control people. But I'm always saying, ‘We mustn't let them steal our joy,’” says Delaine Le Bas. Upon canvas and calico: bodies emerge in neon pink and green; photos of a young Le Bas are collaged alongside embroidery and sequins; goddesses look outwards, unafraid; text sprawls over itself. “We’re not having that,” she laughs.

Commissioned and co-curated by Glasgow International and Tramway, Delaine Le Bas’s Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding explores both the mythologisation and discrimination of Romani, Gypsy and Traveller communities, with a distinctly feminist, experimental lens. Interweaving popular culture and mythology with reflections on movement, land, and her childhood, the exhibition pulls together both new and existing works in a spectacularly expansive and immersive installation. Following Le Bas’s Turner Prize 2024 nomination for her presentation at Secession, Vienna, the exhibition is poignant and utterly singular.

The exhibition also marks Le Bas’s return to Tramway, following To Gypsyland (2013), a travelling research project, in collaboration with Barby Asante, exploring Romani, Gypsy and Traveller communities in cities throughout the UK. As such, she knew the space well; the scenography was undertaken by herself and her partner Lincoln Cato. “Some pieces, we knew where they were going. They had their own place already,” she says.

Tapping into Le Bas’s own Romani heritage, an aluminium frame wagon, titled Off Kilter, has been commissioned by Tramway and Glasgow International for the exhibition. “It's about movement, but non-movement; the romanticism of being nomadic, but if you are nomadic, no one wants you to be nomadic,” she says. “It's off-kilter – so it doesn't function, it doesn't work. And so it's about being captive as well within this and trying to escape from it.”

A number of her works reference “linguistic engineering”, recalling a previous exhibition in Maxim Gorki Theatre, Berlin – Delaine Le Bas: Beware of Linguistic Engineering. “I think it's about language, misuse of language, abuse of language, language being used as a tool to exclude people but also to confuse them. And how many words have double, triple, quadruple meanings,” she says. Such is especially true for those who have English as an additional language; language then becomes yet another means to other and to isolate.

Rather, Le Bas is keen to speak outwith fear, welcoming all in. Textiles meet sculpture, sound, text, video – the exhibition spans across forms. “I'm trying to give access points or different doorways for anyone to access the work,” Le Bas says. Hierarchies are dismantled, delightfully so: Le Bas’s work is for all to engage with, in a multitude of ways. “If there’s only one door in and out and something happens – we might be in trouble. You want some fire exits.” In times of emergency and fear, Le Bas’s art offers alternative routes; such routes are necessary but the art is all the richer for them, regardless.

Throughout, her work continues to reference itself, returning to itself. ‘Fear’ is written in thick, black ink, repeatedly; a trouser suit appears in a film, a photograph, a remake hung up elsewhere; Mickey Mouse finds himself upon a tapestry, a jumper, and a canvas book. Recycling and reclaiming materials throughout her career, Le Bas is now creating from scratch more often than not. “I've sort of run out of space in the house because it's so much archive material, bits and pieces. And also because of the nature of the work that I'm making – the scale of it's just got bigger and bigger and bigger,” she says. Some pieces within the exhibition were made on-site, in Tramway, the large floor space and high ceilings a necessity.

Throughout, Le Bas renders visible this process of “bigger and bigger and bigger”. A number of the works re-appear within the show – smaller, adjusted ever so slightly. “It’s blown up but it’s not identical to it. It’s almost like the embroideries have acted like small maquettes for the bigger pieces,” she says.

A string of numbers – undivided by slashes or full stops – lines the edges of many works, noting their date of completion. “I don't put my name on the front of my work so the numbers have become like a signature but in a different way. And also because people seem so obsessed with numbers,” Le Bas explains. “They also act as records for me because often the paintings take place over a period of days and might even be weeks.” The show’s title continues this, noting the artist’s birth date: Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding.

“Part of it is just a space where people can sit and maybe talk to someone and have a conversation,” she says. Hay bales come together at the end, clustered close and circular. On top, books rest: Le Bas’s Secession publication; her son Damian Le Bas’s The Stopping Places; a Roma women’s poetry anthology, Wagtail. They’re there to be engaged with, to be thought from – much like the show in its entirety. “Just come along. Enjoy it, if you want to.”

Delainia: 17071965 Unfolding, Tramway, until 13 Oct