Maud Sulter and The Living Archive of Diaspora

Curator Pelumi Odubanjo tells us how she’s reimagining Sulter’s legacy through a participatory events programme at Tramway

“It’s not a retrospective, it’s a continuation,” reflects writer, editor and curator Pelumi Odubanjo on the exhibition Maud Sulter: You Are My Kindred Spirit, currently on display at Tramway. For Odubanjo, the late Scottish-Ghanaian artist’s legacy is far from static; instead, it’s an active force ripe for new critical interpretations and creative responses.

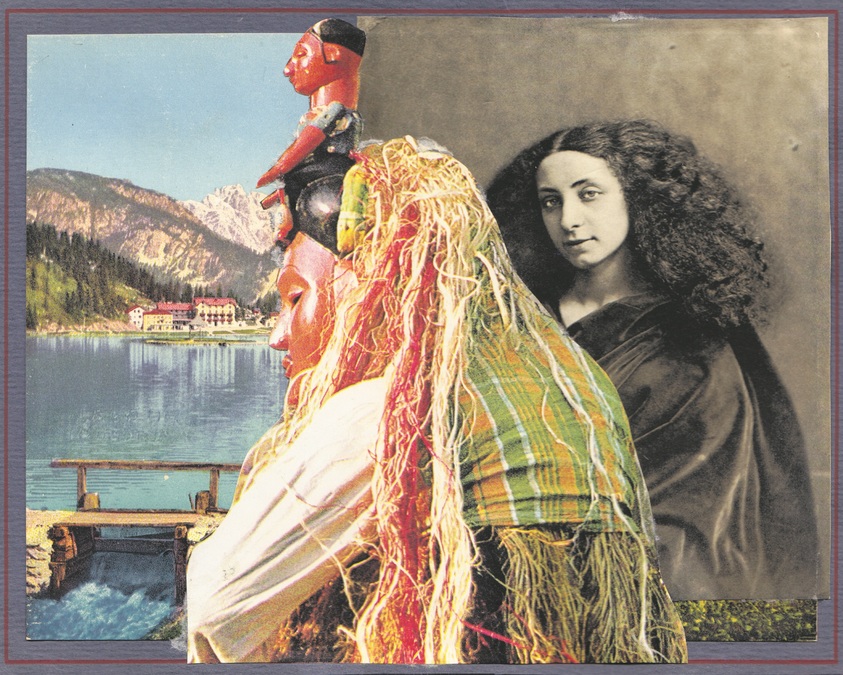

While many might come to know Sulter through her subversive photography that defies the systematic erasure of Black people from art history, this exhibition foregrounds her voice. Archival recordings of the artist’s spoken word works, delivered in her thick Glasgow accent, ripple through the exhibition space, corresponding with photography, collages and moving image. The artist’s political and personal practice is animated as her voice propositions the visitor in dialogue with the visual material, forging a connection that is at once challenging and comforting.

To activate the exhibition, Odubanjo has curated an incisive events programme that resembles a “living archive of diaspora”: an embodied form of cultural memory where Sulter’s work evolves in dialogue with contemporary diasporic experiences. Primarily platforming Black women and non-binary creatives, the programme encompasses film screenings, a poetry recital, a screenplay workshop and culminates in Call and Response: a multidisciplinary forum that centres the practices of Black creatives in Scotland and incites shared dialogue on Sulter’s work and legacy.

For Odubanjo, and the wider curatorial team, it was crucial that the events programme unfolded within the exhibition space itself, ensuring participatory engagement with Sulter’s work. “As I imagine, Maud would have wanted,” Odubanjo reflects, “her work is there for you to engage with and respond to.” A circular gathering spot within the gallery becomes a site of collective reflection. Through this space, the soundscape of Sulter’s spoken word amplifies her rhetorical questions, inviting listeners to reckon with their own positionality. In Blood Money, a poem that examines the personal and historical traumas of colonialism and systemic racial violence, Sulter repeatedly asks her listeners, “Would you?” confronting us with a series of impossible choices. Similarly, in the film installation Plantation (1994), we’re thrust into the abject world of the artist’s womb, challenging us with the question: “Can women have wishes?”

Syrcas. Duval et Dumas Duval, 1993. Image: Estate of Maud Sulter. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022.

Odubanjo’s curatorial vision is shaped by her imagined companionship with Sulter. She speaks of Sulter as if she is a guiding presence. “Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to know Maud in person,” Odubanjo says, “but I definitely feel like I’ve taken one step closer to understanding how she thought and the way she worked.” Central to this understanding is Sulter’s relationship with Glasgow, which in the words of Odubjanjo, was vital to the artist’s practice “as a place, an environment, [and] an ecology”.

The living archive of diaspora as an act of collaboration and reclamation is expressed through the programme contributions of Natasha Thembiso Ruwona and Tomiwa Folorunso. In 2022, Ruwona and Folorunso created maud., a filmic mediation on Sulter’s legacy. Its title, lowercase and punctuated by a full stop, suggests a deep intimacy, as if a lover's name scribbled down on the envelope of a letter never sent. Odubanjo, similarly refers to the artist by her first name; "Sulter" just doesn't cut it. Screened at Tramway, maud. was bookended by a heartfelt in-conversation between the filmmakers and some of the creative contributors, including Adebusola Ramsay, Khadea Santi and Zoë Zo, Zoë Tumika & Zoë Guthrie. Each connected by the life-affirming moment of discovering Maud's work as Black creatives making work in Scotland. Each connected by the ongoing fight for just cultural memory that is not obscured by white supremacy.

One anecdote stood out: artist Camara Taylor came across Maud's work in a 20 pence book in a secondhand sale. That 20 pence chance encounter is potentially seismic in creative influence, but it can’t be that only the serendipitous are afforded the chance to know her. With You Are My Kindred Spirit, we are on our way for Maud to become a household name in Scotland.

The final audience member’s question, met with gasps of affirmation, seemed to distill the room’s collective sentiment: “What do we owe Maud?” Among the answers was a recognition of the visibility of friendship, collaboration and spirit in the face of the “impossibility of being Black and Scottish”, in the words of another audience member. As Odubanjo explains: “It’s about remembering [Sulter] as a person, rather than as figure of the past.” By uplifting Sulter’s voice and the continual impact of her practice, Maud Sulter: You Are My Kindred Spirit refuses the nostalgic confines of traditional retrospectives, embracing instead an ever-evolving archive of ideas. In doing so, Sulter and her work is propelled into the present, her provocations increasingly urgent.

Maud Sulter: You Are My Kindred Spirit, Tramway, Glasgow, until 30 Mar