Gray's Glasgow: A Queer, Working-Class Cartography

Inspired by Alasdair Gray's mythologising of Glasgow, an archive-based exhibition maps the city through a queer, working-class lens

In 1977, the artist and writer Alasdair Gray took up his first, and only, stable visual arts job as Glasgow’s artist recorder. Based out of a storeroom studio in the People’s Palace, Gray painted the streets and faces of the East End at a time when civic redevelopment plans threatened to flatten the area and erase its working-class histories. Gray’s portraits were democratic, taking as his subjects everyone from poet Edwin Morgan to Simon McGinley, a local bricklayer. They were all, in Gray’s eyes, worth at least their weight in canvas and paint.

The City, the current exhibition at the Alasdair Gray Archive, takes its lead from Gray’s equalising practice. Curated by Holly Rennie Brown, the exhibition spotlights working-class and queer communities in Glasgow, drawing an intuitive and deeply personal map of the city along its back alleys. In Renfield Lane you’ll find a wristband for a Ponyboy club night at Stereo, on Bath Street a love note handwritten on the back of a receipt from Bloc. These time capsule scraps are mounted and framed, presented like borrowed geocaches held up briefly as art.

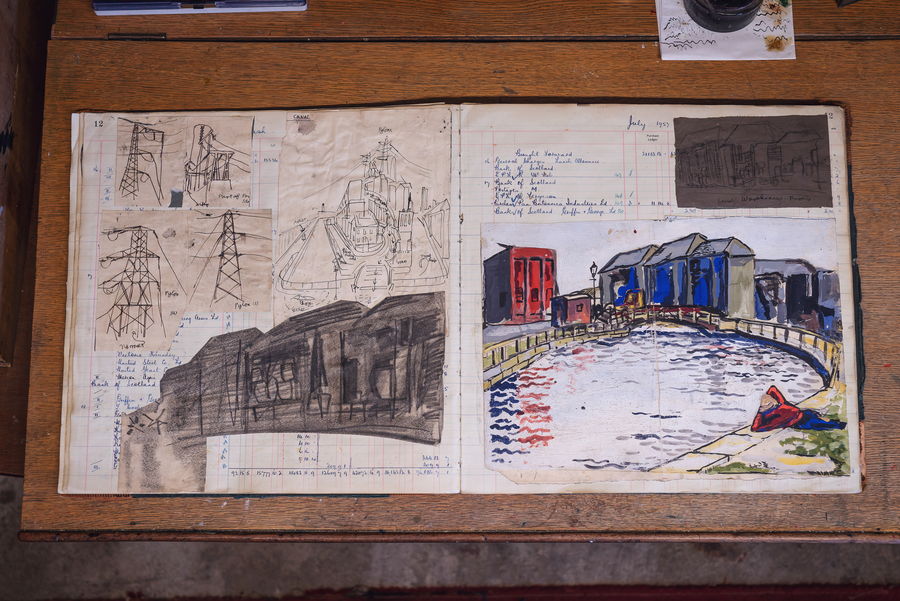

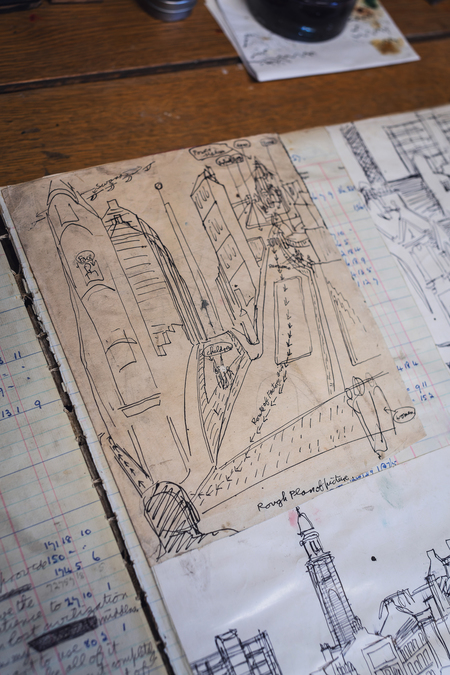

Gray was skilled at injecting aesthetic value into found objects. The archive is a wellspring of junk, like a ledger he found in a skip in Garnethill. Its pages crinkle with the ink of his distinct cursive, which weaves between abandoned expense reports and PVA’d film photos of a disappearing Glasgow. Some sketches are recognisable as early sections of Cowcaddens Streetscape in the Fifties (1964), an oil painting completed a year before the area was all but demolished to make way for the northern flank of the M8 inner city ring road. His streams of consciousness evoke snippets of writing that he later adapted for Lanark, the dystopian setting of which was likewise inspired by the debris of Cowcaddens.

Brown’s exhibition calls to mind the oft-quoted line of Lanark’s protagonist, Duncan Thaw: "If a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants can live there imaginatively." Gray’s work took strides to mould that Glasgow imaginary, but, as Brown’s exhibition emphasises, class boundaries compound geographic ones in the stunting of the imagination. The slog of hospitality work stifles creativity, keeping the working-class distracted while the managerial class envisage their future. Yet, Brown’s framed tokens of restaurant and retail work subvert those spaces into sites of radical care, fugitive creativity and solidarity. One note, given to them by a friend while working in retail at END on Ingram Street, reads 'I Love You’ / ‘You got this'. It forms a poetic couplet written across two perfume strips.

This philosophy of radical care is fundamental to the curatorial practice of the archive’s custodian, Sorcha Dallas. With support from Creative Scotland's Open Fund, Dallas commissioned The City alongside a mentorship scheme for an early-stage curator. Following Gray’s 'socially conscious model of making' and insistent citation of his inspirations, Dallas’s curatorial approach seeks to address overlooked histories and transform them into a catalyst for meaningful connection through commissioning creative responses like Brown's. Central to this commissioning process is an imperative to facilitate the creative practice of those ordinarily denied the time, energy or resources to pursue theirs alone.

As someone who lived near the breadline all his life, Gray depended on the generous labour of others to facilitate his practice. He paid them back in tradesman wages and any flattery his literary and artistic talents could offer. His greatest compliment to those closest to him was to commit them to art. For his cleaner Kelly Crosan, for example, he one day wrote a poem in place of an agenda. It begins: 'Our Kelly has the magic touch! / Dirty floors and messy tables she soon has shining clean. / Just when you [think] she’s finished work, / our Kelly starts again.' Much as he did in his work for the People’s Palace, even in his personal life Gray canvassed attention for unsung workers by investing in them an aesthetic value nobody had yet thought to grant them. Brown does a similar thing in the exhibition.

However, where Gray plays with perspective in a kind of fabulation of working-class Glasgow, Brown is more documentary. Their exhibition is rooted in their lived reality – one that has always existed in its own queer imaginary but omitted from the heteronormative city map, pushed into back alleys and underground. That personal reality flows outwards, through the crowd in a low-roofed club, behind ‘staff only’ doors and back into red-brick tenement homes. From this community web, Brown follows in the footsteps of Dallas, who follows Gray, down Glasgow’s cobbled lanes to forge a new map.

The City, The Alasdair Gray Archive, The Whisky Bond, Glasgow, until 13 Nov

thealasdairgrayarchive.org