Dundee Contemporary Arts: The first 20 years

Turning 20 is a major milestone birthday, but what does it mean in gallery years? Dundee Contemporary Arts are finding out this month as the multi-functional arts centre moves into its third decade

Talking to the first Exhibitions Director of DCA, Katrina Brown (now Director of the contemporary art gallery The Common Guild in Glasgow), she describes how the relatively Ronseal-esque name of Dundee Contemporary Arts was actually a controversial choice at the time. “There had been a consultancy report commissioned by Dundee City Council and the university. Around that time, there were a lot of discussions about what it should be called.”

One potential name was The Garage, as a nod to its previous function. “This report said that whatever happened with the name, it shouldn’t mention contemporary art because people don’t like it, and it would be advisable not to include the word Dundee.”

Pre-DCA: The Factory, art and DIY skate culture

Immediately before this initial period of the building becoming an arts centre, the DCA had another subcultural life, and another name. The Factory was the name given to the DIY skatepark that had previously sat on the site in the Nethergate, and pre-DCA, that name had stuck. Artist Raydale Dower has featured in these pages for his five-star Glasgow International project last year, but is also a primary source for The Factory days. “I spent a lot of time skateboarding in The Factory. At that time in the early- to mid-90s it was the only indoor skatepark in Scotland and home to a healthy underground social scene. It was DIY, self-built and self-organised, people travelled from all over Scotland to skate there… a creative hub before DCA was even on paper.”

Dower continues: “Built with a DIY ethos, in many ways a perfect example of an anarchic social model, the top floor was tidied and regularly swept up, the wooden ramps built, related and maintained. The police knew that skateboarders were using the building but were happy to let them carry on as it was a positive use of derelict space and ensured a certain benign guardianship.

“The Factory was a motivating reason for why I chose to study at Duncan of Jordanstone and throughout my degree it continued to influence my artistic development. As a creative space you could argue The Factory laid the groundwork and paved the way for the DCA. This might be a stretch of the imagination but it’s nice to think that the creative energy from those times is stored within the walls of the DCA and still permeates the exhibition spaces.”

The change from Scotland’s indoor skate park to a major cultural hub was relatively quick. As Brown describes: “It went from an idea to an opening in the space of five years, which is quite speedy.” It was the beginning of lottery funding in 1995 that was a definitive catalyst for the DCA to come into existence and the City Council that led the project and still owns the building. “The idea that they saw an opportunity, got the funding together and opened the building within the space of five years seems almost impossible now.”

DCA and DJCAD

As well as the beginning of the council’s pursuit of the new lottery funding, the University of Dundee is also an important player in the origin story of DCA. “The university was an important partner in the whole development. [It was] attracting lots of researchers from all over the world to work in medical sciences. Through the process of recruiting, people would often ask about the cultural life of the city: is there an arthouse cinema? Is there an art gallery? So the university could understand that in order to bring people to live here but also to keep them there, they had to seed an enhanced cultural life.”

Not only attracting the university researchers, the DCA (along with Cooper Gallery and GENERATOR Projects) continues to attract an art audience to the city that would likely not otherwise make it to Dundee. The DCA's current Exhibitions Director Eoin Dara describes how his relationship with the city grew out of his engagement with DCA, well before he was employed there. Dara describes his initial encounters with the city while he was studying as an undergraduate student: “ I used to get the train from Edinburgh to Dundee and just walk from the train station to the galleries, see the shows and go back to the train.”

Conversely, the artist Scott Myles lived his young life in Dundee, studied in Duncan of Jordanstone and it was as the DCA arrived that he left the city. For him, the artistic energy of the city was also a result of the concentration of creative talent that was buzzing inside the walls of DJCAD at the time. In the years before 1999, Myles was skating in The Factory then studying in DJCAD with a set of tutors that were each in the midst of their rise to national and international renown, including Graham Fagan, Cathy Wilkes and Victoria Morton.

Elba by Scott Myles

“They brought quite a lot of interesting people to the art school. We also had this amazing art history tutor Alan Woods, who was a personal friend of Ralph Rumney, one of the founders of the Situationist International [a subversive artistic movement that sought to radically alter people’s relationship to the city, culture and mass media].

“I can remember Alan giving a lecture in third year and he had taken slides of a walk, from the art school, down Perth Road, down past the garage which would become the DCA, then down to the current site of the V&A. And the joke was that at that point, you couldn’t get to the waterfront because the pavement came to the big city road and you couldn’t get across.” This was a lecture that was also a dérive, a journey through the city that is taken with heightened awareness and with the intention of creating new encounters with familiar surroundings. Myles remembers it fondly, and as a moment of being presented for the first time with new and radical concepts.

This exciting period of DJCAD’s history was recognised by the DCA during their last big birthday, when they marked turning ten with a show that included Myles alongside some of the artists that were in DJCAD a few years above and below him, all of whom went on to national and international acclaim.

New Artists, Exciting Spaces

A year before this, Rabiya Choudhry was in the show Altered States of Paint, one of two group exhibitions that featured her work in DCA. She fondly describes the unique experience that she had, remembering staying in the comfortable flat for artists (inside the DCA itself) and cooking dinner for the curator, Graham Domke. At the suggestion that this sounds sophisticated, Choudhry rebuts that dinner was a ready meal in the oven that she accidentally burnt. For Choudhry, every member of staff went “beyond” and she describes the sense that everyone was happy to be there.

Choudhry acknowledges the importance of being in this show, and meeting people that she would later work with again. The show combined Scottish artists with other well-known painters from across Europe and beyond. Recently, Choudhry went to the earliest emails in her personal archive and looked back at the communications she had in advance of the show. Reading them, she remembers being at work and typing out replies, and that a computer bug meant that scrambled the ends of her emails. With characteristic modesty, Choudhry describes “that [it] was a bit of a punt” programming her alongside the other renowned international artists in the 2008 group show.

“Being asked by [Graham Domke] to do the show was the first time I’d been seen in a big institution like the DCA.” Specifically, she describes having “room to breathe” within the group show and that normally in other galleries you don’t really have that. “It was amazing to have the chance to show in such a world-class space.”

Throughout our interviews, people would mention other folks to talk to, singing their praises and how much they contributed to the DCA. Speaking to one person that’s been involved leads to the next talented person that invested their mind and lived out important parts of their professional lives around this institution.

The DCA print studio.

Myles brings up the important place DCA Print Studio occupies as a space for artists to produce and experiment. He describes a series of prints he made alongside his friend, the late Kevin Hutcheson. “I’ve always found the Print Studio to be completely supportive of my work and a lot of artists have had great experiences with Annis [Fitzhugh, Head of the Print Studio].”

While Myles was in the studio, he and Hutcheson were trying to use the big print table, neither having ever used it before. It was all going wrong – in a conventional technical sense. But for Myles, this was an important time and space to do the kind of experimentation that would inform later works. Tracking down these early experimental works, they included David Standing 4th May 2004 and David Sitting 4th May 2004, which is now part of the collection of the Tate.

Dara eloquently describes his own sense of pleasure, responsibility and ambitions as he rounds off his second year in the job. He remembers "moving here, and very specifically living here right in the city, and getting a sense of the civic responsibility that you have in a job like this, and which DCA has as a public institution.” For him, this “was and continues to be the most exciting aspect of the job. What we’re doing is carrying on a legacy, to look at the programme that Katrina Brown and others have developed here historically, to maintain that level of ambition and experimentation and a real trust in artists and a real support towards artists. That’s something that DCA has done well."

The Present and Future of Dundee Contemporary Arts

Each interviewee talks about the importance of DCA “continu[ing] to push the boat out to the Tay” (as Choudhry puts it), and hoping that the two decades of experimentation and trust in artists continues to define the institution as it continues. Speaking to Dara, it’s clear the 20th birthday celebrations are only a small part of the expansive and ambitious programme that shapes the rest of the 2019 for DCA.

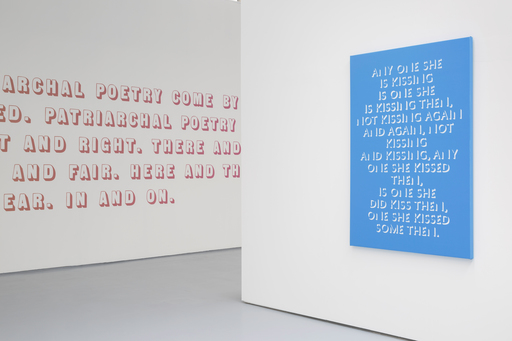

“One thing that Beth [Bate, DCA director] and I are doing, is looking at projects that have happened up until now and starting specifically to look out for and make space for voices or positions that have been overlooked or underrepresented by dominant culture to date. That work is very much taken from a feminist position… Over the past year, it has been a deep privilege to work with the likes of Eve Fowler, Kate V Robertson and Margaret Salmon.

"Then, in the upcoming programme, in our Summer Season, we are working with a major new commission looking at trans and nonbinary bodies under capitalism and finding ways to resist under those discriminatory structures. Then later on in the year we’re doing a large show with Alberta Whittle that’s sparking off lots of different things from her Margaret Tait film.”

Install view of Eve Fowler's DCA show.

Going further, Dara describes “trying to be open institutionally to live acts of learning. We’re not worried about getting all the right answers behind closed doors then to put up a very confident front. There’s still space for taking risks and running experiments, what does and doesn’t work and we have to be open and honest about those things to make progress.”

With its municipal-sounding name, Dundee Contemporary Arts could be mistaken for having established institutional status – though the status of public amenity arguably doesn’t mean security or survival in 2019. In fully appreciating the DCA making it to 20, it’s worth bearing in mind, as Katrina Brown describes, “these institutions are independent, they’re not city authorities or national institutions. They’re independent companies with massive fundraising targets and fragile bases.”

Brown describes visiting Dundee regularly and the success of the programme, including the recent shows by Lorna McIntyre and Margaret Salmon that the gallery's current Head of Exhibitions also mentions proudly. As the DCA continues to produce consistently high-quality output, it could be easy to miss the hard graft it takes to continue producing the exhibitions and content that it does.

That’s especially the case in the current climate of arts funding. Brown says: “We know there’s been a massive erosion of budgets available for exhibition programmes. These things are really precious. So many people will talk about shows they saw [at DCA] as students or at school, and they’re working in the arts now.” Brown lists off some prolific arts professionals and artists who all at a formative stage had DCA “as their local gallery.” For her, these institutions as “important” as they are “fragile”.

“In that intervening 20 years, anything that’s free seems weird now. Everything is monetised now.” There’s something integral for Brown about “going into a gallery for free, and you can spend two minutes or two hours there. There are some people that don’t understand that, and they just think it’s weird. Anniversary celebrations are always just a reminder about what’s good about something, why it matters and why we still go and care about it. It’s a useful, invaluable thing for any city to have a space like DCA.”