Where Are the Disabled Photographers?

We zoom in on how Stills challenges the institutional barriers that prevent disabled photographers from greater exposure in the Scottish art scene

'Where are the disabled photographers?' is an events series by Stills, hosted by their Creative Learning Coordinator, Louise McLachlan. Over the past year, two events invited photographers with lived experience of disability to share ideas about their practice and education. In May, the series will travel for a new iteration at Peckham 24, an annual contemporary photography festival.

The series is titled with a strong provocation for change. The incredible photographers exemplified in this series show that there is an abundance of disabled photographers in Scotland, but that they are not widely visible. McLachlan remarks to me, and I personally have a similar experience, that “even though I work in the arts, I don't know many disabled artists.” The experience of many of the event participants suggests that this disparity is partly due to a lack of support by photography education providers.

Participant Chris Belous notes that lack of clear communication and bureaucratic processes stand in the way of access, and Natasha Williamson speaks about the bullying she experienced at school and college – from both students and teachers. McLachlan mentions a harrowing statistic reported by the University of Glasgow in 2024 that disabled artists earn 70% less than non-disabled artists, and it’s clear from these educational experiences that not only does disability present a barrier in itself, but so do the attitudes of education providers who actively prevent the development and success of disabled artists.

Stills School – an alternative photography school for 16-25-year-olds who face barriers to engaging with the arts – positions itself as part of the solution to the event title’s question. Many of the participants could not access formal education but Stills School’s focus on access presented a new opportunity for learning and development without traditional barriers. It is free to attend; individual access requirements are prioritised; you cannot ‘fail’ it; all equipment is provided, and there is one-to-one tutoring.

Amy Iona. Courtesy of Stills.

This kind of environment allows for the success of disabled photographers such as the many who participated in this event series, sharing their stories, practices, and educational experiences. I was struck by one participant in particular – Ink – who attended Stills School and has created some inspiring photomontage work depicting cathedrals. They quote the poet Jay Hulme, who said that 'cathedrals are trans, trans people are cathedrals’ – because of how they are "so often partially knocked down and rebuilt". Ink’s use of trans bodies in their cathedral montages are visually stunning, and also provide them comfort – to think of trans people as “old and ancient, as a community who often dies early.” Ink really appreciates the space of Stills School to develop their practice and suggests that accessibility is “not a separate process… but just the process of learning itself.

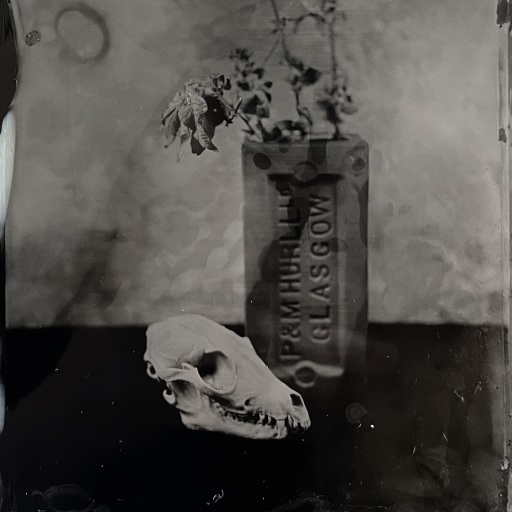

Sasha Saben Callaghan also uses photomontage, and works primarily digitally – noting that accessible studio space in Edinburgh is extremely hard to find. Other photographers have also had to find ways around production barriers: Eleanor Buffam developed a cyanotype practice, photographing plants in her garden when chronic illness left her unable to leave the house. Many of the participants in this events series have a socially engaged practice, blending their artistic work with advocacy. Natasha Williamson’s socially engaged photography, for example, focuses on “portraying people the way they want to be seen.”

McLachlan’s passion for helping these artists become more visible is clear, driven by her own experience of inaccessibility in mainstream education, which she left at 16. She speaks about her work as an artist and arts worker as being inextricably intertwined: “I really know what it’s like to be on the other side of the glass when nobody will open the door, but I also know the impact it makes when that one person opens the door.” Louise’s beautiful work Mōtae (shown at Stills and MIMA) displays her care and attention towards disability through the depiction of bodies in motion in a grid of self-portrait photographs. What stands out to me about this work is its emotional softness created by a blend of photo and painting: a sense of calm; a feeling of a gentle breathing in and out as the bodies move silently across the grid. This kind of softness is visible too in her work at Stills, where she leads by example in creating a supportive environment for learning and making: “I use my own lived experience and access requirements as examples to showcase that [Stills School] is a space in which it's safe to do so.”

The disabled photographers are here, and as Louise says, they “just need a platform and investment.” More institutions – both educational and artistic – need to put this kind of work into exposing and uplifting the myriad of disabled photographers and artists in Scotland. As Ink astutely comments: “What I experienced here at Stills School was brilliant, but that doesn’t mean it should be rare.”