Shoving From All Sides: Edinburgh Art Festival Platform 2020

The annual showcase of emerging Scottish artists Platform returns for its 2020 edition, featuring four diverse practices. Mark Bleakley, Rhona Jack, Susannah Stark and Rabindranath A Bhose introduce their work

Each year, the four-person Platform exhibition runs concurrently with the Edinburgh Art Festival, showing the work of four emerging artists selected from an open call. This year, it’s a standalone exhibition. Rather than organise the artists around a singular theme or topic, the artists selected usually have lines of association that motivate the group that emerges during the selection process. This year, there’s a delicate line of solidarity between the artists, as they each consider (from different directions) collective principles of sharing, recycling, free appropriation and equity.

Mark Bleakley

For artist-choreographer Mark Bleakley, the body itself as a physical heft can be shared and loaned. He says the work here is informed in part by “the protest die-ins when you physically give weight to a cause, and the power of that.” In the first part of his film Giving Weight, Bleakley shares fragments of a workshop he facilitated, where participants were asked to think through the concepts “grounding, groundlessness and inertia.” These come from his inquiry into “the spaces that create collectives, like the rave, or a mosh pit or religious ceremony.” The second part follows the Jeopardy! gameshow format as answers are given as clues, before revealing the question. “What’s taking the ground from you?” is one question. The suggestions for answers include: “the state, or bigger social structures that have a control over your body, your weight or how you exist.”

Bleakley cautions, “I’m not trying to make grand statements, but provoke the viewer to think about how your weight is active and passive... Throwing your body into a mosh pit is like a surrendering, or marching at a protest is a stamping and it’s an affirmation of your body in space and time.” He also refers to chain linking, used by protestors and police alike, “trying to think about this spectrum when you’re actively using [these body-based tactics], versus when somebody is actively using [them] against you... Because I work with dance, I always come back to the principle that we are thinking with our bodies. Thought is not just [in the head], it’s throughout us.”

Rhona Jack

Similar to Bleakley’s understanding of thinking with the body, Rhona Jack speaks about the importance of actively moving while she’s making and forming new ideas. “A lot of the processes I’m using are repetitive so they leave a lot of time for thinking. It’s a lot more difficult for me to try sitting cold and coming up with an idea.”

Jack’s installation comes, in part, from being surrounded all her life by immediate family members’ skilled textile practices, and plotting this personal experience within the history and the global economics of garment manufacturing. “The conditions in textile factories in most cases haven’t improved in 100 years. It’s just that they exist in other parts of the world.”

While Jack is conscious of the exploitation of workers in factories making mass-produced clothes, she juxtaposes this with what is produced, namely “clothes that become special to the person wearing them. They can be a really comforting thing, a way of expressing your personality. At the same time, they’re tossed away. I’m showing the textiles I’ve handmade alongside these mass-produced textiles, and I want to bring forward the sense that a person made these, as well.”

This work also follows on from Jack’s commitment to working with recycled materials. She describes being known by people around Dundee for finding uses for materials that would otherwise be headed for landfill: “They’ll contact me about something they think I’ll be interested in, and ask me, do you want this? I’m starting to realise how easy it is to get anything you need, and it doesn’t have to be new. I’ve seen how art can be very wasteful so more and more, I’m trying to use what’s around me”.

Susannah Stark

Susannah Stark shares Jack’s interest in working with found materials, whether literally with objects that her mother finds on the shore, or more broadly by collaging together existing images and field recordings. For instance, within Stark’s audio piece, she combines musical elements and songs responding to histories of habitation in Scotland with field recordings, made while walking in and around Pictish Brochs, in peat bogs, and around her home in Glasgow. The locations are often where there are very real present-day socio-political effects that stem from the oppressive expropriation of the Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th centuries.

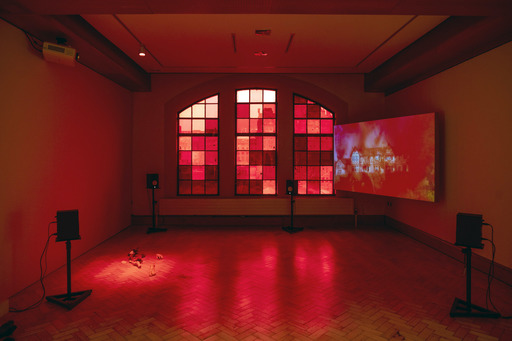

The installation of this soundwork itself is inspired by brochs, an ancient form of dwelling found in Scotland, the archaeological remains of which show they were round in their structure, centred around a hearth. As well as creating this “sense of space”, for Stark this work is also about “the expressiveness of the voice. I’m really interested in softness, so I tend to utilise that a lot in the work. Something that seems soft and gentle, there can be lyrics that are more loaded or come from a really specific source. A strange combination of being lulled into something but then there’s also an intention within it.”

Alongside the sound work, Stark has also been developing collages of visual materials, which include as one of their elements images of Scotland used in tourist advertising. She speaks of these as a “reckoning” of some of the stereotypical postcard fantasies of Scotland. “I use a lot of red [in these works]. It casts these promotional images in a different light. Some element of criticality comes with recolouring them, they’re not just washed out in this dreamy way. They become quite heavy images.”

For Stark, Scotland “is sold as idyllic, that it’s good for your holiday because it’s empty and there are unspoilt beaches and woodlands. It’s clean and pure. But people do live here, and they always have. A lot of people have been evicted so maybe that’s why it’s emptier than it used to be. People were put out [of] the way to make profit.” She refers to Andy Wightman’s book The Poor Had No Lawyers as a key text for understanding the development and persistence of an exploitative system of land ownership in Scotland.

Rabindranath A Bhose

With Stark referencing stone circles and ancient dwellings in her arrangement of her AV tech, a similar collision of ancestral, mystical and contemporary materials comes in Rabindranath A Bhose’s large vinyl drawing installation of an elephant trunk and its reference to Ganesha. Made from arrows, and pointing limbs and other directional symbols, it moves from floor to ceiling. Alongside this large-scale drawing, Bhose also includes a pamphlet of new writing.

Speaking of their themes and intentions, Bhose notes: “I think in terms of methodology or what mood I want to go for, it’s just a feeling of perversion, as a form of disruption. The texts that I write are often quite perverted. That comes from a homosexual [and transmasculine] history, and also a history of bodily abjection. Perversion, humour, disruption, speculation... it does all come from a place of love as well, and hopefulness, wanting to call into being modes that can feel cathartic or have a possibility to build on, or just a little moment of redemption. By sharing the texts with people and having it resonate with them, or when they find it funny or strange, it really makes a difference from just having [images, words, stories] rattle around your own head.”

Within the work, Bhose describes making a metaphorical “quilt” that incorporates symbols, myths, imagined and biographical elements. “For me the whole purpose of making this work, or to be honest of making any work, writing or engaging in any art practice or conversation with others, is really a seeking of a personal spirituality or trying to piece one together. And I’ve noticed other people doing that too. You might be culturally embedded in some religions or mythologies, but I definitely have to make my own piecemeal, like a quilt, to feel that I have some faith and motivation. I feel like in queer worlds, especially queer creative worlds, that’s where you find other people trying to do that... When the systems around you don’t make sense for you and the people you love, you inevitably seek out other systems of knowledge or of making sense.”

As each of Platform 2020’s artists tend to their respective fields of social, personal and political enquiry, there is the reminder of American poet and anarchist activist Diane di Prima’s tender advice from her 1971 poetry collection Revolutionary Letters, that:

NO ONE WAY WORKS, it will take all of us

shoving at the thing from all sides

to bring it down.

Platform, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, until 29 Nov, free – booking required

edinburghartfestival.com/whats-on/detail/platform-2020