Smashing Monuments, statues, and collective memory

The UK premiere of Sebastián Díaz Morales’ film Smashing Monuments questions the functions of monuments in our collective memory – but also whether our cities can really meet our everyday needs

A colossal, monolithic LED screen fills Collective’s circular City Dome space, sitting amongst the scattered monuments atop Calton Hill. Raucous music erupts, stomping feet threatening to crush everything, luminous details of the subject’s shoes and socks filling the screen. What follows are five segmented filmic portraits – each with their own dedication to a monument that inhabits the streets of Indonesia’s sprawling capital city Jakarta.

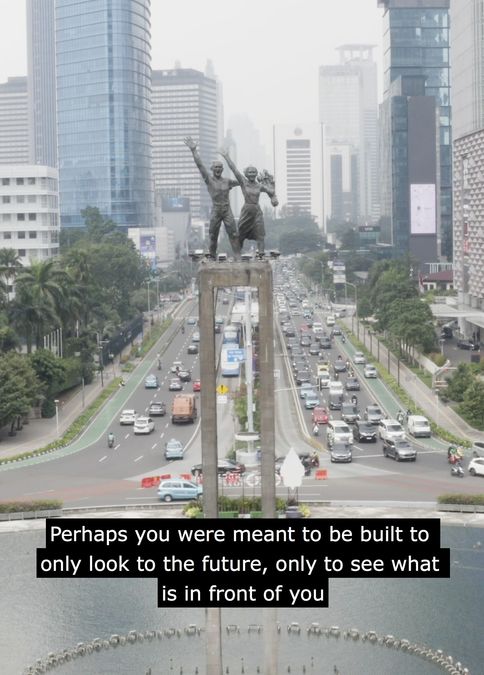

The preface to each person’s testimonial shows only their feet walking, running, charging along the pavement, blown up to colossal scale – as gigantic and imposing as the statues that are the subject of the film. It features stunningly epic (and sometimes near-vertigo-inducing) aerial and drone footage of Jakarta. Sebastián Díaz Morales’ radical and revelatory experiment with scale here is one of the most alluring and hypnotic aspects of viewing his film. The running time of 50 minutes feels more like like 15.

The film follows five members of the Indonesian art collective ruangrupa as they wander the streets of Jakarta, pausing to engage with the various monuments that stand high above them. These half-improvised dialogues make reference to the rapid social and economic changes that the city has experienced and how these changes have informed post-colonial Indonesian personal and collective memory. Originally screened at documenta fifteen in Kassel, Germany in 2022 (which was curated by ruangrupa), the collective invited Morales to make the film in response to the collective’s activities. Founded in Jakarta, Indonesia in 2000, the collective's work is based on a holistic social and spatial practice strongly connected to Indonesian culture. Friendship, community and solidarity, sustainability are central to their practice.

Most of the monuments depicted in the film were erected in the 1960s, following Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch in 1949, after a turbulent independence movement that was deeply entangled with the global power struggles of the Second World War. They have remained a consistent and steadfast presence in a rapidly changing metropolis. The members of the collective engage with a range of these monuments, including the Pembebasan Irian Barat Statue (which celebrates Indonesia’s independence from Dutch colonial rule) and the Pancoran monument, which celebrates Indonesia’s aviation industry. Each member of ruangrupa addresses their respective statue as if they are alive and breathing.

This animation of the monument provides an interesting contrast to discourse in the UK, where monuments are often depersonalised, with the focus instead on their particular historical context. One of the collective’s members, Gesyada Siregar, relates the Tugu Tani Statue to her own youth and her mother’s youth, an ode to the recent passing of her mother. The monument remains the only static thing amidst the transient flow of cars and people – but also amidst the transience of life and death.

A still from Smashing Monuments by Sebastián Díaz Morales. Image courtesy of the artist

The timing of the film’s creation feels particularly potent in more than one way. Indonesia is currently preparing to move its capital from Jakarta to Nusantara, which is currently being constructed, from scratch, on the island of Borneo. This is partially due to the fact that Jakarta is sinking – rising sea levels threaten to inundate one-third of the city by 2050. It is also a move to de-centralise the island of Java (which is home to many of Indonesia’s largest cities) and to share economic opportunities amongst the thousands of islands that form this vast archipelago. In the wake of the climate crisis, and its detrimental effect on our urban spaces, this decision makes us consider whether the contemporary city really meets the needs of its citizens – and whether they will be able to continue meeting these needs in the future. The film forces us to consider whether our cities' civic architecture and spaces really reflect the values of the society we live in.

While in Morales’ film, the legacy of Dutch colonisation in regards to Indonesian contemporary urban spaces seems rather limited, Britain’s colonial legacy is alive and well in our civic spaces. While the cost of living crisis and the war in Ukraine has drawn our attention away from the issue of problematic monuments, it’s easy to forget how animated and divisive the conversation became during the pandemic. While conversations had been happening for years in activist circles – accelerated by the Rhodes Must Fall movement that started in 2015 at the University of Cape Town in South Africa – the colonial legacy of our public monuments was disturbingly absent from mainsteam political discourse until 2020.

Morales’ film infuses Edinburgh’s dense network of colonial monuments with an intense poignancy. One of the monuments in this network is the controversial statue of Henry Dundas in St Andrew Square, an 18th-century politician partially responsible for delaying the abolition of the slave trade. In June 2020, protestors graffitied the statue, and in response in 2021, Edinburgh City Council installed a plaque commemorating enslaved Africans who suffered because of the prolonging of slavery into the 19th century. However, Scottish academic Sir Tom Devine and some of Dundas’s descendants criticised the content of this plaque as being historically inaccurate and overplaying his role in delaying abolition. Regardless of whether Henry Dundas did delay abolition or not, he was still a fervent imperialist – his involvement with the East India Company saw the pillaging and exploitation of Indian resources on a mass scale.

In March 2023, Edinburgh City Council stated they would remove the plaque dedicated to enslaved Africans from the monument. To this day, the statue of Dundas still stands, high above the streets of the New Town, unchanged since 1821.

Smashing Monuments, Collective, Edinburgh, until 11 Jun