Reclaiming the Gallery: Alia Syed, migration, and the CCA

Alia Syed's solo exhibition, The Ring in the Fish, explores what role imagination plays in migration. The curator reflects on nurturing Alia's creative vision within an institutional framework that is, at present, stifling community expression

I first came across Alia Syed’s work in 2018, at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, where she had presented Eating Grass (2003) as part of the exhibition Delirium // Equilibrium. I remember thinking I had seen her work before, perhaps during my university film studies course? Years later in 2023, while researching South Asian filmmakers in the UK, I came across Alia’s work yet again, and eventually invited her to be part of an exhibition I was curating in India the same year. It was only in 2024 at the beginning of this project, that I was able to meet her for the first time in Glasgow.

Over the past decade, progressing from student to curator, I have formed a slow friendship with Alia, in her absence and her presence; a friendship now punctuated by sprigs of curry leaves and fists clenching boiled eggs that she brings for me. It is my first extended collaboration with an artist developing a project from scratch. Within the gallery space, our discussions have been shaped by her perspective as a filmmaker and mine as a curator, giving rise to creative ideas on how best to present these narratives – but also occasional disagreements.

Based between London and Glasgow, Alia has been making 16mm films since the 1980s. Born in Swansea to an Indian father and a Welsh mother, she grew up between India, Pakistan, and the UK, spending a significant part of her formative years in Glasgow, a city that continues to hold personal meaning. The Ring in the Fish marks her first major solo exhibition in this very city. Straddling film, photography and sound, this exhibition is a collaborative body of work that draws inspiration from the tale of St. Mungo – patron saint and founder of Glasgow – and the English folk story of the fish and the ring. The title becomes a conduit for the transformative nature of both individual and collective narratives inviting an intimate exploration of what role imagination holds in migration, and how these images are carried across multiple generations of migrants to create new psychic landscapes and enable new ways of being.

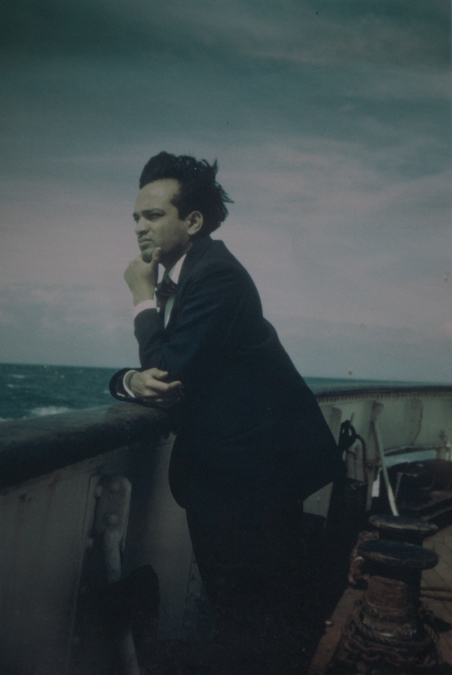

Photo of Syed Ali Ahmed.

This exhibition therefore, becomes a kind of homecoming and is dedicated to her late father, Mr Syed Ali Ahmed. Besides a pensive photograph of a young man on a ship with his hair blowing in the wind, his stories are not directly part of the exhibition but emerge instead in Alia’s anecdotes. You hear about his deep love for gardening despite his failed attempts at growing strawberries, and the neighbours’ frustration with his wild, overgrown garden; his life as a respected physicist, his Muslim faith and his political journey shaped by his commitment to the Trade Union movement; his founding of the West of Scotland Friends of Palestine and Scottish Friends of Bosnia. She tells you how he would drive Yasser Arafat around Glasgow on his visit, and of a young Humza Yousaf running to offer him an umbrella as he sat in the rain in a CND demonstration against the Trident Missile base in Faslane – that he grumpily denied.

Her father’s presence becomes symbolic of the many families who migrated to Britain and Glasgow between the 1950s and 70s in the wake of Independence and the Partition, seeking a better life in a post-war economy. Over the past five-and-more years, Alia has gradually uncovered an archive of stories and personal histories of individuals – through anonymous archival records and photographs, community networks, women’s friendship circles and even chance meetings. The exhibition presents only a small part of this wider research: a collection of oral narratives with each story shaped by absences, silences and inevitable gaps in memory. Alia reimagines these memories through film while also employing the gallery’s architecture both visually and sonically, to guide viewers in their engagement with these stories.

One of the central works in the exhibition is a film in the first gallery that features the sport of Kabaddi, an ancient game of tag-and-tackle from the Indian subcontinent. The game relies on marked lines dividing teams and territory, requiring a player to continuously chant “kabaddi” while on the opponent’s side; but if they pause to take a breath and/or are tackled, they lose a point. Alia uses this game, as well as the ritual of breathing, as a metaphor for survival: for migrant bodies navigating ways to endure within unfamiliar environments; for resisting oppressive systems that seek to classify and control lives; and for the lingering legacies of colonialism that have divided territories across South Asia and continues to fragment land and communities on a global scale.

Beyond this metaphor, the film prompts us to reflect on the architecture of the CCA as an institution – one that Alia recalls having occupied as a teenager when it was still The Third Eye Centre; one that I first stepped into five years ago. Over the decades, it has held countless histories of its communities and offered a shelter to so many lives. Alia and I now occupy this very architecture with this exhibition, yet we unexpectedly find ourselves adrift, struggling to sustain this exhibition within an institutional framework that is suddenly drawing boundaries and fragmenting the very communities it was meant to support.

As I write this, Police Scotland surrounds the CCA and artists and cultural workers face aggression. The CCA Board’s recent indecisive statement around endorsing PACBI (The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel) has left the public in a state of chaos and frustration. For us, this came two weeks after the opening of the exhibition, following an already exhausting period of uncertainty beginning with Creative Scotland’s defunding and later reinstatement, accompanied by the CCA’s temporary closure last year, both of which resulted in delayed timelines.

Further, since issuing its statement, the Board has, in a recent and deeply troubling turn of events, responded to its own community with violence – by engaging the police, restricting access to the space, and carrying out yet another temporary closure. These decisions, made without any prior consultation or communication with the current exhibiting artists, have left us grappling with the situation by ourselves. Until last week, Alia and I had chosen to continue with the exhibition as our own form of reclaiming the space – an act of resistance from within the institution by women from the global majority, bringing to light the very histories that are often tokenised or erased. But in the light of this week’s events and ongoing institutional silence, we are left trying to determine what it even means to continue.

Our solidarity lies with all those who are working to reconstruct accessible art spaces while also fighting for Palestinian liberation – which is our collective step towards a larger ongoing fight to free the world from the throes of colonial and capitalist structures. We hope that our combined voices adds to the growing pressure on the institution to take an accountable stance.

The Ring in The Fish is a solo exhibition by filmmaker Alia Syed and curated by Shalmali Shetty, originally scheduled to be on view at the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow from 17 May - 26 July 2025