Queering the City: Edinburgh Art Festival 2023

As Edinburgh Art Festival returns this month, The Skinny meet Sean Burns and Tarek Lakhrissi to discuss their artistic contributions to the festival

With a new chair, Gemma Cairney, and new director, Kim McAleese, 2023’s rendition of EAF sees a change in pace, with the festival condensed down into just over two weeks, from 11-27 August. Maria Fusco’s and Margaret Salmon’s History of the Present will open the festival on 11 August at 8pm at The Queen’s Hall. The film, which was also shown at Art Night in Dundee in June, reflects on Fusco’s experience of life in Belfast during the Troubles – but moves away from the familiar visual and aural tropes most people are accustomed to from the news coverage that screened in the 1990s. The festival’s keynote speech takes place the following day on 12 August (2-2.30pm) at the National Gallery of Scotland. The lecture will feature provocations from Belfast-based Array Collective and Beirut-based feminist organisation Haven for Artists (who will also be in-residence in Edinburgh throughout the festival). The lecture will reflect on one of the key aspects of the programme – how international exchange and collaboration can operate in contexts of crisis.

The following night, on 13 August (from 7pm), Alberta Whittle’s performance The Last Born – making room for ancestral transmissions will take place at Parliament Hall. The performance will explore themes of abolition, rebellion and ancestral knowledge, building upon her current exhibition create dangerously at National Galleries of Scotland’s Modern One. At Edinburgh Printmakers’, Glasgow-based artist Christian Noelle Charles’s exhibition WHAT A FEELING! | ACT I will discuss racial identity, love and community care through the lens of a Black woman. Moving through printmaking, video and performance, Charles will explore the movements, rhythms and body language of women of colour. Her screenprints – intricate, richly textured portraits of friends and collaborators – are a highlight. Meanwhile, Australia-based artist Keg de Souza has filled Inverleith House with branches of eucalyptus, alongside batik prints and an audio work developed while in residence at Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Gardens. Shipping Roots continues until the end of the festival. At Collective, DANCE IN THE SACRED DOMAIN is a new commission by Glasgow-based artist Rabindranath X Bhose, part of the Satellites programme for emerging practitioners working in Scotland. Bhose, working with the full height of the exhibition space, meditates on Scotland’s bogs (historically used as burial sites) as metaphors for ‘passing on’, both in terms of queer identity and death.

Bhose’s exhibition is one of many queer practitioners featuring in the festival: one of the key strands of the festival this year examines how queer communities and creatives resist amidst a climate of government and media attacks on trans rights. Earlier this year, the UK Government blocked Scotland’s Gender Recognition Bill from being legislated – the first time this has happened in regards to equality laws. Although the bill has its own limitations, it would have made a significant difference in improving the health and wellbeing of many trans people in Scotland, by removing the requirement for a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria as well as lowering the age to apply for a gender recognition certificate from 18 to 16. This intervention signals both the Conservative government’s contempt for trans people and for Scotland’s devolved parliament. The government in London is currently also stalling a bill which would ban harmful conversion therapy – with some 400,000 people in the UK alone having experienced some sort of attempt to ‘change’ their sexuality or gender identity. This is just one instance of the Conservative government using queer and trans people as political pawns. More widely across Europe, right wing governments are unleashing a wave of anti-LGBT+ sentiment, with Italy voting in a right wing party into power last year. Finland currently has a far-right party in its coalition government, and the far right are making gains in Spain, Sweden and Austria.

So, against this backdrop of growing institutional and everyday transphobia and homophobia, how do creatives respond? Many artists and collectives in this year’s festival make timely interventions into this particular contemporary cultural and political landscape – looking both at historical methods of resistance, but also dreaming of divergent futures.

Dorothy Towers. Credit: Sean Burns.

Sean Burns’ film Dorothy Towers, which is being screened throughout the festival at The French Institute, lovingly and nostalgically looks at the Clydesdale and Cleveland tower blocks in Birmingham’s city centre. The two residential towers were a crucial queer social space during the 1980s and 90s (partially due to their proximity to the city’s gay village) against the backdrop of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Burns’ film recalls the experiences of some of their residents, which move between elation, joy, love, trauma, loss and heartbreak. The microcosm of the tower blocks speaks to analagous queer, largely working-class experiences in the UK during this period – although it is deeply indebted to the city of Birmingham and its unique characteristics. For the artist, this history is very much part of our present – and our future. Burns says he is interested in "how the lives of past queer people influence the worlds we inhabit and the behaviours that we enact today – the film grows out of and is a form of archiving, inherently containing a legacy dimension."

Burns decided to shoot the film with 16mm – an intentional move he says, to ingrain a physicality into the work: but one with higher stakes. "With 16mm, you have one opportunity to catch the shot, which inherently creates tension – I want tension and vulnerability, blur and mistakes. Similarly with people: how something/one deviates from convention is where the character resides. You enter a dialogue with the technology, in which its erratic will co-authors the outcome. I like it when certain decisions are determined by limitation." On a physical level too, analogue film also operates as "an imprint of experience in physical form – it introduces a tactile element accordant with the work’s surfaces: concrete, bodies, flesh, tires, tarmac and tiles."

I ask Burns about the translation of this specific, microcosmic history into that of Edinburgh – a city whose history and demography is vastly different to that of Birmingham’s. He hopes, for one, that the screening of the film will draw attention to queer-led and focused collectives and resources currently operating in Scotland’s capital. A public programme will accompany the screening, and will include collaborations with Lavender Menace Queer Book Archive, Lothian Health Services Archive and Cole Collins, an academic at Edinburgh College of Art. Burns hopes that the film "will catalyse deeper conversation for connections and disparities to emerge. I also want these events to function as something of an alibi for people to meet one another and learn about the incredible resources, for example, Lavender Menace has to offer."

Dorothy Towers. Credit: Sean Burns.

Burns acknowledges the complexity of displaying this microcosmic narrative on a national scale and he purposefully leaves space for further narratives and conversations to grow and flourish: "Making legible a local history raises interesting political questions: what happens when the experiences of individuals becomes material for an artwork viewed on a national scale? Although the film somewhat packages the narrative – albeit directly told in the residents’ words – it felt important to retain an obfuscated atmospheric element, a feeling that there’s infinitely more to tell."

Meanwhile, Tarek Lakhrissi, who is presenting an exhibition and accompanying performance for the festival, works with sculpture, performance and filmmaking – all bound up in his love of poetry and prose. I wear my wounds on my tongue (II), currently on display at Collective, is as curious as it is enchanting. Three fleshy, luminous pink and orange sculptures lie on squat, black metal plinths in the centre of the City Dome space. They are at once appealling – almost irresistible to touch – but also threatening, with their sharp ends casting the tongues almost as daggers (a recurring symbol in the artist’s practice as of late). The ambient, richly textured sound work which accompanies the sculptural works was made in collaboration with composer Victor da Silva and references, at once, French cloud rap, the FKA Twigs song Meta Angel and an excerpt of the soundtrack from the early-2000s TV show Dark Angel. The artist’s voice, rendered deep and distorted, gives way to pulsing, heartbeat-esque thuds that rumble the City Dome. An ambient hum then mutates into something more melodic, short flourishes of a melody appearing then seemingly fizzing off into the ether. The fleshy sculptures and heartbeat-like rhythms of the sound create a particularly internal, bodily experience.

The exhibition is inspired by, and dedicated to, the late Malaysian-American poet and activist Justin Chin, who passed away in 2015. Lakhrissi was first introduced to Chin’s poetry two years ago while in Brussels, and his exhibition at Collective is named after one of Chin’s poems. The artist describes Chin’s poetry as a combination of "political statements against racism and heteronormativity, despair and hope, philosophical reflections, raw emotions and gay sexual encounters." The current political rhetoric and language used to talk about queer and trans people is deeply concerning, and I ask Lakhrissi about how language can be used to resist. He reflects, "I think for many centuries queer, but not only, people of colour, women and/or trans people have been using different ways to resist norms and violences that are based on gender, sexuality and race. Language is one form of resistance, but the idea is to not become a symbol, or to simplify things that are too complex to resolve or to answer. I just want to argue that language is, personally, a fluid space where I can play, question and confront myself."

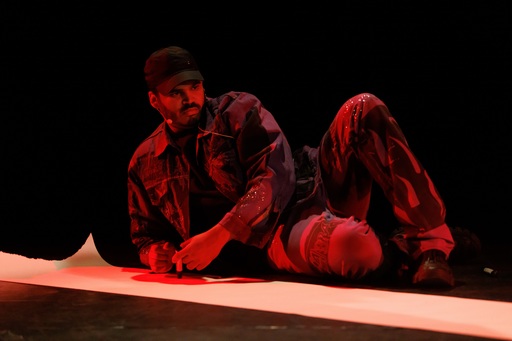

BEAST!, Terek Lakhrissi. Credit: Hervé Veronese.

On 26 August, Lakhrissi will perform BEAST!, which has previously been shown in Berlin, Zurich, Basel and Paris. A collaboration with singer and friend Makeda Monnet, he describes the performance as a "ritual to call a ghost." The work is inspired by French-Arab thinker Louisa Yousfi’s text Rester Barbare. The artist says the text works to recentre discourse around "the question around threat and empathy towards Black and Brown 'masculine bodies.'" Victor Da Silva, joining Lakhrissi on the night, will create a soundtrack to accompany the performance, which will make calls to the ancestors as part of a ‘cleansing ritual’. BEAST!, along with the many other facets of the artist’s practice, is a ‘celebration’ of how queer, trans and people of colour can not only adapt, but flourish in situations of danger.

I ask Lakhrissi about the relationship between the exhibition at Collective and the performance later in August: "I would argue that BEAST! is where I am more directly connected to the magic of spoken word, music, and singing. It’s two different facets from my own practice. Performing is definitely where I feel much more connected to the audience because I am present, because we are sharing the same space and time. The universe we can create can be so cathartic."

Edinburgh Art Festival, various venues across Edinburgh, 11-27 Aug

Sean Burns, Dorothy Towers, The French Institute, daily 10am-5pm, 11-27 Aug

I wear my wounds on my tongue (II), Collective, until 1 Oct, daily 10am-5pm. Tarek Lakhrissi will perform BEAST! at The French Institute, Sat 26 Aug, 6pm